Equinor’s route to the wider world

This overview article addresses the developmental aspects of Equinor’s history as an international company in that part of its business which involves exploration for and production of oil and gas (E&P). Links are provided to articles about Statoil/Equinor’s engagement in the individual countries referred to.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sources are provided in the articles concerning the individual countries featured on this website. Since the company’s name has varied, Statoil, StatoilHydro and Equinor are used in line with the official designation at the time concerned.

Establishment phase

The first decade of Statoil’s history represented the start-up phase. With Arve Johnsen as CEO (1972-87), it was built up into a fully integrated national oil company along the whole value chain from exploration, through production and transport, to processing and sale of petroleum products. Eight years after its establishment, the company began to show a profit. The Statfjord field was by then on stream as a veritable cash cow.

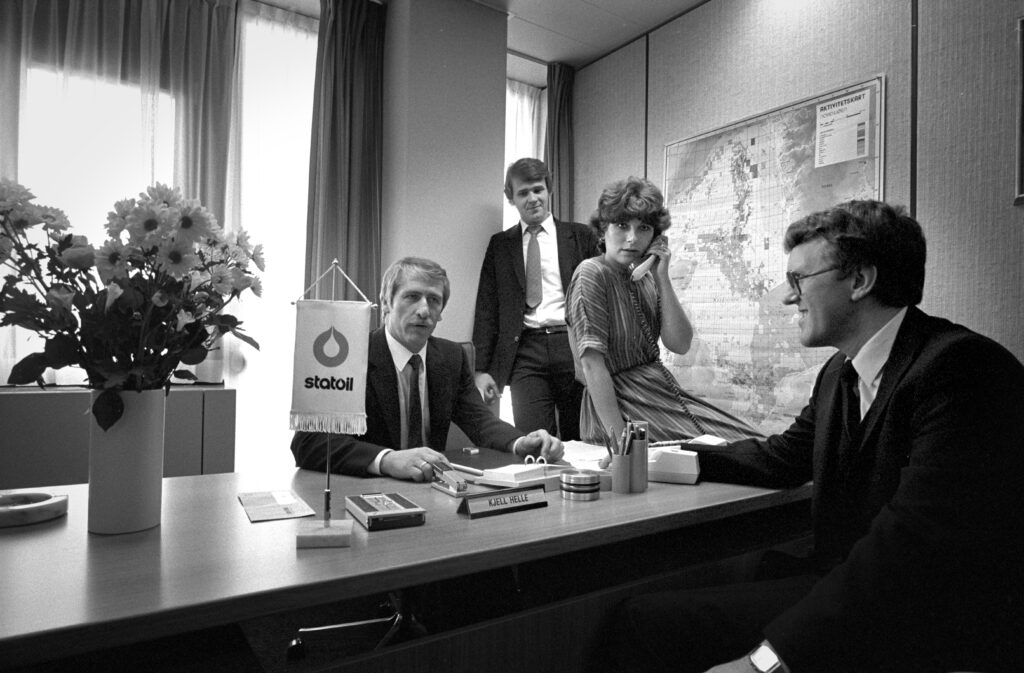

Norway’s organisation of its oil industry, and Statoil in particular, attracted international interest. As early as the 1970s, foreign delegations were frequent visitors. Contacts and exchanges of experience with other countries were important, and a strategy was developed in the 1980s for collaborating with national oil companies (NOCs) in relevant countries which had such state-owned enterprises. This was known as the NOC-NOC approach.

Statoil established its first foreign upstream subsidiary in the Netherlands in 1983, and followed up later in the decade with companies in Denmark, China and the UK. In Chinese waters, the company developed its first foreign offshore field and operated it for a time. As Norway’s closest offshore neighbour, Britain remains very important for Equinor in terms of both petroleum and renewable energy.

Into the world with BP

During Harald Norvik’s time as CEO, from 1988-99, Statoil’s internationalisation seriously picked up speed.

Although the company made a series of discoveries on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) in the 1980s and 1990s, a conviction prevailed that fewer new resources would be found off Norway after 2000. While gas output and exports would increase, oil production was expected to decline. To offset the latter trend, it would be good for Statoil (and Norway) if additional resources could be secured in other countries.

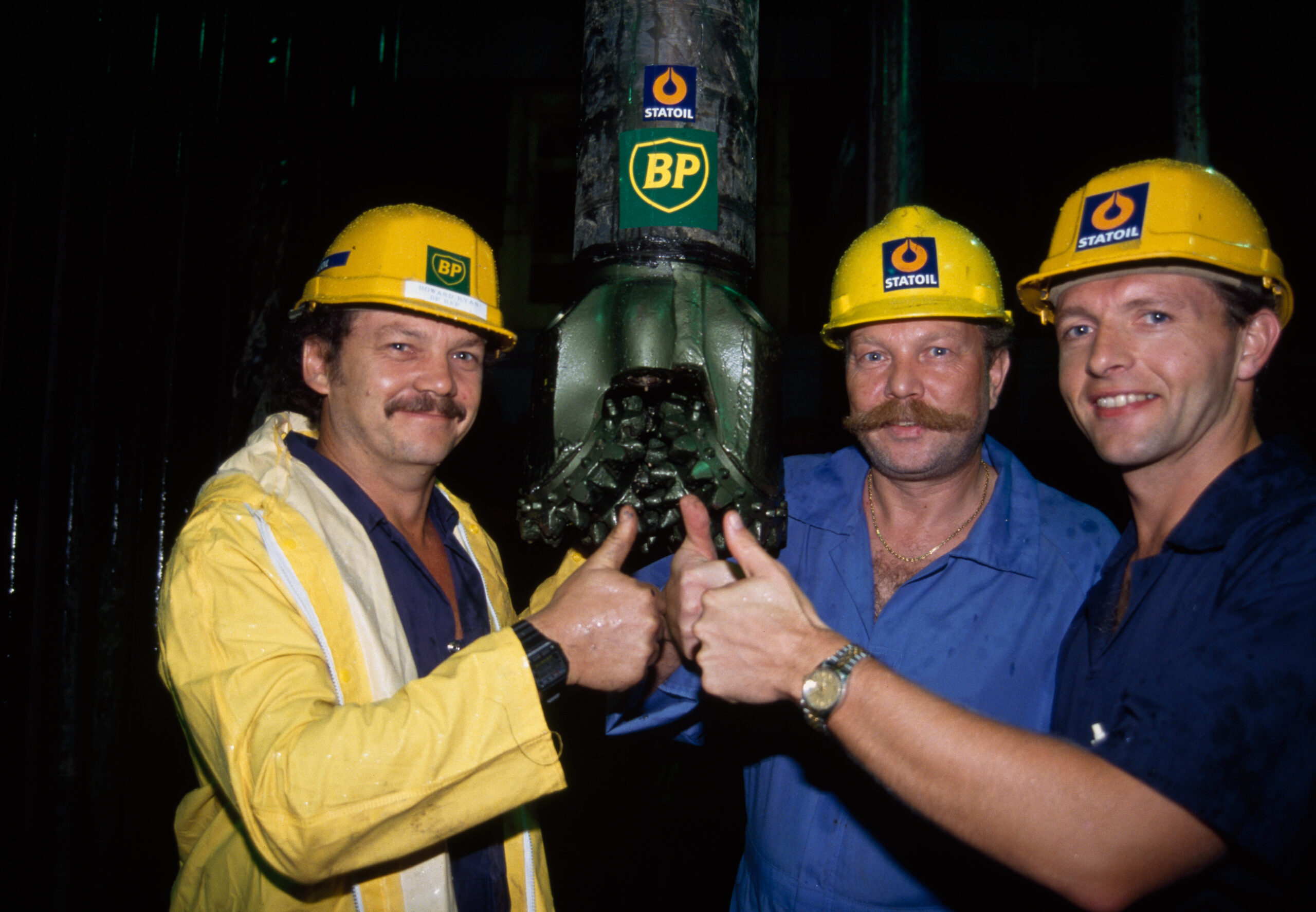

A strategic alliance entered into with British Petroleum (BP) in August 1990 became very significant for the company’s further development. The oil price slump in 1986 had hit BP hard. It needed more capital as a result of restructuring and privatisation in the UK petroleum industry, and of hostile share purchases which had to be bought back. Statoil could offer this after Statfjord and Gullfaks had become operational, and also wanted to become established in other countries.

The agreement with BP covered E&P in selected areas internationally, joint gas sales in the UK market and technological research and development. Through the alliance, Statoil secured footholds for exploration and field development in west Africa (Angola and Nigeria), Asia (Vietnam, Thailand and China) and former Soviet Union countries (Russia, Kazakhstan and offshore Azerbaijan).

Other countries where the company established operations during the 1990s were Venezuela, Ireland and the USA. While the Azerbaijan petroleum fields, in particular, became gold mines for Statoil in the long term, several other foreign ventures failed to live up to expectations. Oil prices were at moderate levels and eventually went into sharp decline at the end of the decade. When Statoil failed to meet its goals with operatorships in several countries, such as Vietnam and Thailand, it pulled out after a few years. The US oil fields were also relinquished, but withdrawal here was not lasting. Statoil would later return to this part of the world with full vigour.

Low oil prices in the late 1990s made a strong contribution to the wave of mergers which washed over the petroleum sector. The big companies amalgamated to become more dominant, make savings and benefit from economies of scale. When BP merged with Amoco in 1998, the strategic alliance with Statoil ended.

Partial privatisation and more freedom

In order to continue pursuing foreign commitments on its own account, Statoil wanted its state owner to become less dominant. Norvik’s strategy was for the company to become publicly listed on a stock exchange. Management would then become accountable to its own board and not have to wait for “permission” from the Storting (parliament). A partial privatisation with the state as the largest shareholder was prepared by Norvik and implemented in 2001 by Olav Fjell, his successor as CEO. From then on, Statoil’s goal was that profits from the NCS should be used to a great extent for the international commitment.

In contrast to the BP period, the company now wanted to concentrate its operations on fewer countries – preferably those which, like Norway, had national oil companies. Emphasis continued to be given to securing operatorships rather than being simply a partner in licences. By leading every activity, from exploration to development and operation of oil and gas fields, Statoil could benefit from its technical expertise.

This involved a long-term growth strategy and gradual organic growth. The company now secured production licences in such countries as Algeria, Iran, Iraq and Tanzania.

Pitfalls in encounters with other cultures

Such internationalisation presented substantial challenges, not only of a practical character but also ethical in nature. The latter arose particularly in undemocratic countries with big oil reserves. In such nations, a significant part of the profits from petroleum production were appropriated by a wealthy elite. Many of these countries also lay in regions with a high level of conflict.

Azerbaijan, Nigeria and Angola fall into this category. So did Iran, which wanted to improve its economic position in the late 1990s after several decades of suffering war and sanctions. It therefore invited international companies to participate in its oil industry. After a while, Statoil secured a licence to develop an Iranian field. It then emerged in the Norwegian media that the company had entered into an agreement on consultancy assistance with a son of the president. The company and its head of international operations were charged with corruption and fined. This scandal also led to the resignations of Fjell and chair Leif Terje Løddelsøl. That meant Statoil’s Iranian involvement never got further than the one project.

Another example is provided by Libya, where Norsk Hydro had become involved in the 1990s and consultants had again been paid in connection with the award of a licence to Saga Petroleum. When Hydro acquired most of Saga in 1999, this issue was not regarded as a problem. In connection with the 2007 merger between Statoil and Hydro’s oil and energy division, however, the circumstances were revisited and – with the recent Iran scandal in mind – an investigation concluded that corruption was involved. As the person with ultimate responsibility, Hydro CEO Eivind Reiten had to resign as chair of the merged company only a few days after the amalgamation had taken place. Following the publication of a report from a commission of inquiry, several other former senior executives in Hydro had to resign from StatoilHydro.

Despite these developments, the merged company remained in Libya. After president Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown and killed in 2011, Statoil even received further licences in the country. Little activity is taking place there because of the unstable political conditions.

Merger and continued growth

Both Fjell and Inge K Hansen, his temporary successor, had feelers out in 2003 and 2004 on a merger with Hydro’s oil and energy division, but these initiatives were unsuccessful. Instead, it was new Statoil CEO Helge Lund and Reiten at Hydro who somewhat later secured the political support required. Following the merger, StatoilHydro ranked as the dominant company on the NCS and was also substantial in an international context.

Lund’s analysis of Statoil when he joined the company in 2004 was that it needed to be promoted up a division in the international oil industry league. One means of achieving this was a more aggressive foreign strategy. In addition to gradual growth and cooperation with national oil companies in other countries (the NOC-NOC approach), acquisitions became more common and a preferred method of expansion.

Such transactions occurred particularly in North America, covering production from Canadian oil sands as well as from US shale gas and oil on land and offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. They took place at a time of rising oil prices, when improved earnings increased competition over resources and made then more expensive to buy. And some of the fields acquired needed relatively high oil prices to be worth producing.

A big commitment was also made in South and Central America, particularly on land in Venezuela and offshore Brazil. The company’s international exploration activities expanded hugely, and were pursued in every continent. It was important to find new resources, preferably in frontier areas offshore.

Among other ventures, the company joined an international consortium to pursue front-end engineering for the giant Shtokman gas discovery made in the Russian sector of the Barents Sea during 1988. But Russia’s Gazprom, which called the shots, did not want to develop the field and Statoil withdrew from the project in 2012.

To ensure the best possible control, the strategy in the foreign commitment was still to secure operatorships for the fields which the company had interest in. Statoil had great faith in its own technical expertise, particularly with subsea technology, and that this could give it an edge when competing with other oil companies in deepwater areas.

Substantial oil and gas reserves were found in such depths off Brazil, Canada and Tanzania. The first of these countries in particular has become one of Statoil’s core areas, where its subsea expertise has found full play.

During 2007-17, the company secured offshore exploration licences in a number of other countries – including Indonesia, Tanzania, Mozambique, Ghana, New Zealand, Australia, Cuba, Colombia, Suriname, South Africa, Nicaragua, Uruguay and Argentina – without achieving any particularly rewarding results. Like a number of other oil companies, Statoil/Equinor has faced a mobilisation of environmental organisation opposed to offshore activity in some of these nations. Australia and New Zealand are particular examples. By 2021, Equinor had withdrawn from most of the countries listed above.

Terrorist threat

The growth strategy took Statoil into countries where political conditions were complex. Although it conducted thorough risk assessments of such states, things nevertheless went wrong on occasions. The worst case was oil-rich but politically unstable Algeria.

During Fjell’s time as CEO, the company farmed into gas fields deep in the Algerian desert. The seller was former alliance partner BP, which wanted to spread the financial risk. Production from these assets was sold to Europe.

In Amenas became a well-known name in Norway after a terrorist attack on this field in 2014. Despite comprehensive security measures, 30 people were killed during the four-day assault – including five Norwegians. The report subsequently written for Statoil’s board concluded that there was little the company could have done to predict the actual attack. It nevertheless identified a number of weaknesses and questioned whether Statoil and its partners were sufficiently involved in security work in the area, and had relied excessively on the military presence there.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/content/dam/statoil/documents/In%20Amenas%20report.pdf.

Statoil/Equinor opted to maintain its involvement in Algeria. Gas production from the desert fields has been profitable, and security measures have been stepped up.

Unprofitable and environmentally harmful

While Lund was CEO, Statoil made a massive commitment to land-based oil and gas production in North America. This largely involved exploiting shale oil and gas as well as oil sands. Such “unconventional” resources require different technologies than offshore production. The company’s previous experience with onshore output was limited to producing heavy crude in Venezuela.

In Canada, Statoil farmed into oil sand projects where the production method used presents several drawbacks. It demands a great deal of space and can cause deforestation over large areas. It is also an energy-intensive procedure, because hot water and chemicals is injected to fracture petroleum-bearing rocks and release the oil and gas. The technique also causes substantial CO2 emissions and possible groundwater pollution.

Overall, these issues led to conflicts with environmental organisations in Canada and the indigenous people living locally. Negative press coverage of the project, not least in Norway, helped to give Statoil a poor reputation. When crude prices sank drastically in 2014, producing from oil sands became unprofitable and Statoil sold out gradually.

A similar story can be related from the USA, but on an even larger scale. Under Lund’s leadership, the company farmed into shale gas and oil fields. It lacked experience with this type of activity and failed to secure sufficient control over its complexities. Much of the operation was left to local employees acquired with the organisation when the original US companies were purchased. Statoil even failed to establish control of fundamental administrative processes.

Stories in Oslo business daily Dagens Næringsliv revealed how expensive acquisitions, squandering of money, unpaid bills and legal cases meant the US operations had run up big losses. In the space of a few years, the company had to write off assets worth some NOK 80 billion on land-based projects alone. Offshore activities in the Gulf of Mexico suffered even bigger deficits (see table).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, Offentliggjøring av rapport om Equinors virksomhet i USA, 9 October, 2020, PwC-rapport: «Equinor in the USA Review of Equinor’s US onshore activities and learnings for the future. Prepared for Equinor ASA’s Board of Directors 9 October 2020»: 28. The fact that producing shale gas and oil, as with oil sands, has major environmental impacts did not improve matters.

| Net impairments US onshore | 9.2 billion USD |

| Net impairments US offshore (Gulf of Mexico) | 4.0 billion USD |

| Net impairments MMP segment | 0.5 billion USD |

| Unsuccessful exploration activity (Gulf of Mexico) | 4.0 billion USD |

| Losses on commercial contracts (mainly Cove Point LNG terminal) | 1.3 billion USD |

| Internal financing costs | 2.4 billion USD |

| Contribution from operating activities | 0.1 billion USD |

| Total (net loss per 2019) | 21.5 billion USD |

[REMOVE]Fotnote: PwC-rapport: «Equinor in the USA Review of Equinor’s US onshore activities and learnings for the future. Prepared for Equinor ASA’s Board of Directors 9 October 2020»: 28

By 2022, Equinor had sold out parts of its onshore engagements in the USA and positions its onshore portfolio for potential new low carbon value chains. Equinor has retained its offshore commitment in the Gulf of Mexico which secures Equinor’s largest source of production outside of Norway, currently delivering more than 50percent of the profits from Equinor’s international upstream portfolio.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Profits up, carbon down in high graded U.S. portfolio – Equinor It also remains offshore Canada. Such divestment has also occurred in several South and Central American countries. That includes heavy crude in Venezuela, where the company is also still present offshore.

International concentration

After Sætre took over in 2014, a gradual shift back towards offshore operations began. Oil prices were heading down at the time towards USD 30 per barrel, and remained low until 2018. The acquisitions in North America had required a price of USD 80 per barrel to be profitable. They were now running at a big loss, and the company sold out.

Following the international Paris agreement in 2015, the climate issue attracted much greater public attention. Many countries, including Norway, undertook to reduce their CO2 emissions.

Statoil has adapted its strategy to these circumstances. With Sætre in the lead, the management wanted the company’s name to reflect a shift in its strategic direction. It was changed in 2018 to Equinor. The company was no longer so much “Stat” (state) after the partial privatisation and a stronger commitment to renewable energy sources meant it no longer concentrated primarily on “oil”. Instead came “Equi”, which stands for equality and balance, and “nor”, which references Norway.

Sætre chose to play down the emphasis on “growth” in the company while giving more weight to “value”. A natural consequence of Statoil/Equinor’s greater concentration on climate and the environment was divestment of unconventional sources such as oil sands, heavy crude, and shale gas and oil.

Internationally, attention was concentrated more strongly on geographical core regions, including Brazil, the USA, Canada, Angola and Nigeria. These were countries where Equinor had operations of a certain scope, a clear competitive advantage and good relations with the government, and was valued as partner. Mergers and acquisitions were still pursued as a strategy for reinforcing the company’s position in the chosen areas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Marten Boon, En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001, Universitetsforlaget 2022.

Offshore wind power represented a completely new growth area. StatoilHydro made its first commitment here off the UK east coast, where the world’s first floating wind farm complex is planned. Investment has also been made in this form of energy off the US east coast. Other countries offering opportunities for offshore wind power include Poland, Japan and South Korea. In addition, Equinor has established its first solar power farms in Argentina and Brazil.

Challenges and lessons learnt

With hindsight, Statoil/Equinor’s foreign commitments – particularly in Lund’s time but also under Norvik and Fjell – create an impression of a company with big growth ambitions. These were so large that they might seem to have overshadowed the complexity and risk of pursuing this type of activity in many countries at the same time.

By and large, Statoil/Equinor’s goal has been to recover oil and gas in ways which cause the least possible pollution. It has largely succeeded in this on the NCS. However, some forms of production – particularly from unconventional resources – will in any event cause high greenhouse gas emissions as well as soil and water pollution. Such output helped to give the company a poor reputation in several countries, and it has gradually sold out of these sources.

Low oil prices in the most recent period, with Sætre and then Anders Opedal as CEO, have forced the company to make savings and to concentrate on international core areas. The list of countries where Equinor operated in 2022 is therefore much shorter than before. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, Equinor’s annual accounts for 2020 were somewhat atypical. But they nevertheless show clearly that the bulk of its revenues hail from the NCS. Then come the USA, Angola and Brazil as the most profitable foreign commitments. Further down the list come Azerbaijan, Canada, the UK, Algeria and Nigeria.

The change of name from Statoil to Equinor has made its involvement with renewables more manifest in the company’s communication with the world at large. Its most important revenue source in the commitment to a green shift will be the NCS. The strategy is still to build on the company’s own offshore and deepwater expertise in Norway and other countries. Offshore wind power is the new growth area. Equinor is aiming for a future where oil and gas play a less prominent role, and renewables will be more important energy sources both in Norway and internationally.

arrow_backFrom telex to TeamsRefined swap dealarrow_forward