Going ultradeep off Brazil

This represented a good strategic opportunity for Statoil. Two decades later, Brazil has become one of the group’s most important international priority areas for oil and gas – and for an emerging commitment to solar energy. Around 2000, Statoil was standing on its own two feet internationally after a decade-long collaboration with BP had ended. Management’s goal was still to become more like the big international oil companies, so the group needed to continue pursuing international growth.

Such expansion was intended to be organic and generally achieved by establishing a presence in countries which – like Norway – had a national oil company (NOC). This was known as the NOC-NOC strategy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil developed the NOC-NOC strategy in the late 1980s as its first model for international growth, which was directed at energy-rich developing countries. This approach built on the company’s technical strengths in deep water and its roots as a successful NOC hailing from a peaceful country without a colonial history. Source: Ole Johan Lydersen, 3 November 2021. The goal in these countries was to secure access to resources and obtain operatorships, in many cases in exchange for sharing its expertise. Strong progress had been made by Statoil with technology used to develop offshore oil and gas fields, for example, and it had a high level of expertise in subsea technology.

Statoil’s involvement in Brazil followed the NOC-NOC model. The fact that Norwegian and Brazilian subsea specialists were already fairly familiar with each other was an advantage, making it easier for the group to establish a good relationship with Petrobras – which, like Statoil, had been partly privatised.

Two exploration licences were initially secured in the Santos basin in 2001. Statoil then reopened its office in Rio de Janeiro.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2001. The group reactivated its Statoil do Brasil Ltda subsidiary and the Rio office in mid-2001. Both company and office had previously operated from 1997 to the beginning of 1999, but were closed because of investment restrictions and low international oil prices. Source: Per Harald Larsen, by e-mail, 17 November 2021. Further licences followed in 2004, and the group held operatorships in three of the five exploration areas it then had access to.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2004. Interests were secured in two more deepwater blocks in the following year.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid, 2005.

Peregrino – Statoil’s spearhead

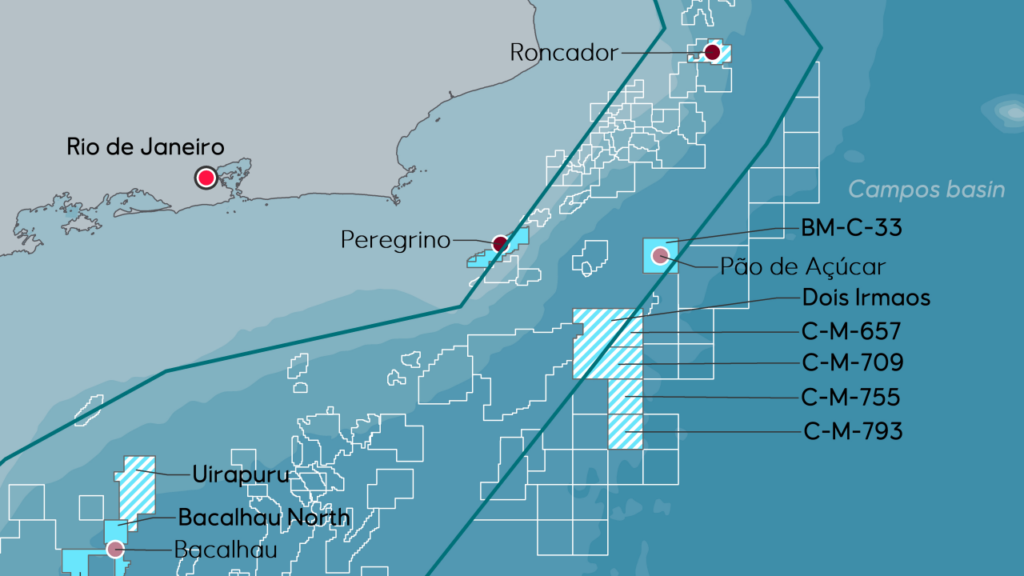

The first Brazilian field Statoil produced from was the Peregrino heavy oil discovery in the Campos basin, about 85 kilometres off Rio de Janeiro.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Heavy oil is liquid petroleum with high viscosity (normally over 10 cP) and specific gravity.

It was fellow Norwegian oil company Norsk Hydro which originally secured a 50 per cent interest in the field. This holding consequently became part of the StatoilHydro portfolio with the 2007 merger. The company then acquired the remaining 50 per cent from America’s Anadarkos. China’s Sinochem Group paid USD 3.1 billion for a 40 per cent stake in 2010.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sinochem to become 40% partner of Statoil in Peregrino oil field in Brazil – equinor.com.

Statoil developed the field with two wellhead platforms, Peregrino A and B. From these, oil is piped to a floating production, storage and offloading unit (FPSO Peregrino) for processing and transfer to shuttle tankers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, StatoilHydro, 2007.

On stream from 2011, the field was challenging to produce because the oil was extremely heavy and viscous. To improve recovery, Statoil therefore introduced technology developed in Norway for installing electrical submersible pumps (ESPs) in every well in order to impart sufficient pressure to the wellstream. Implementing this development earned Statoil a good reputation in Brazil and a solid starting point for continued operations there.

Up to 2017, Statoil alone had invested NOK 20 billion in Peregrino.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Investments in Brazil, Inventure Management, 2017. The spending has not stopped there. After a third wellhead platform – Peregrino C – comes on stream in 20922, the field’s producing life will be extended by 20 years. This facility is to be tied back to a network of oil production and water injection wells in order to reach larger areas of the reservoir and increase the recovery factor.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Equinor, 2019.

Brazil: a core area

In the 2009-13 boom years, with high oil prices, a number of Norwegian companies became aware of the opportunities offered by Brazil. Innovation Norway registered 83 of them in the country in 2014, with almost half of these oil-related.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Norske leverandører bruker milliarder i Brasil”, TU, 13 November 2014. That was followed by the price slump of 2014-18, when the oil companies generally reacted by scaling back their operations and concentrating new commitments more narrowly. This meant a sharp downturn – and downsizing – in the supplier sector.

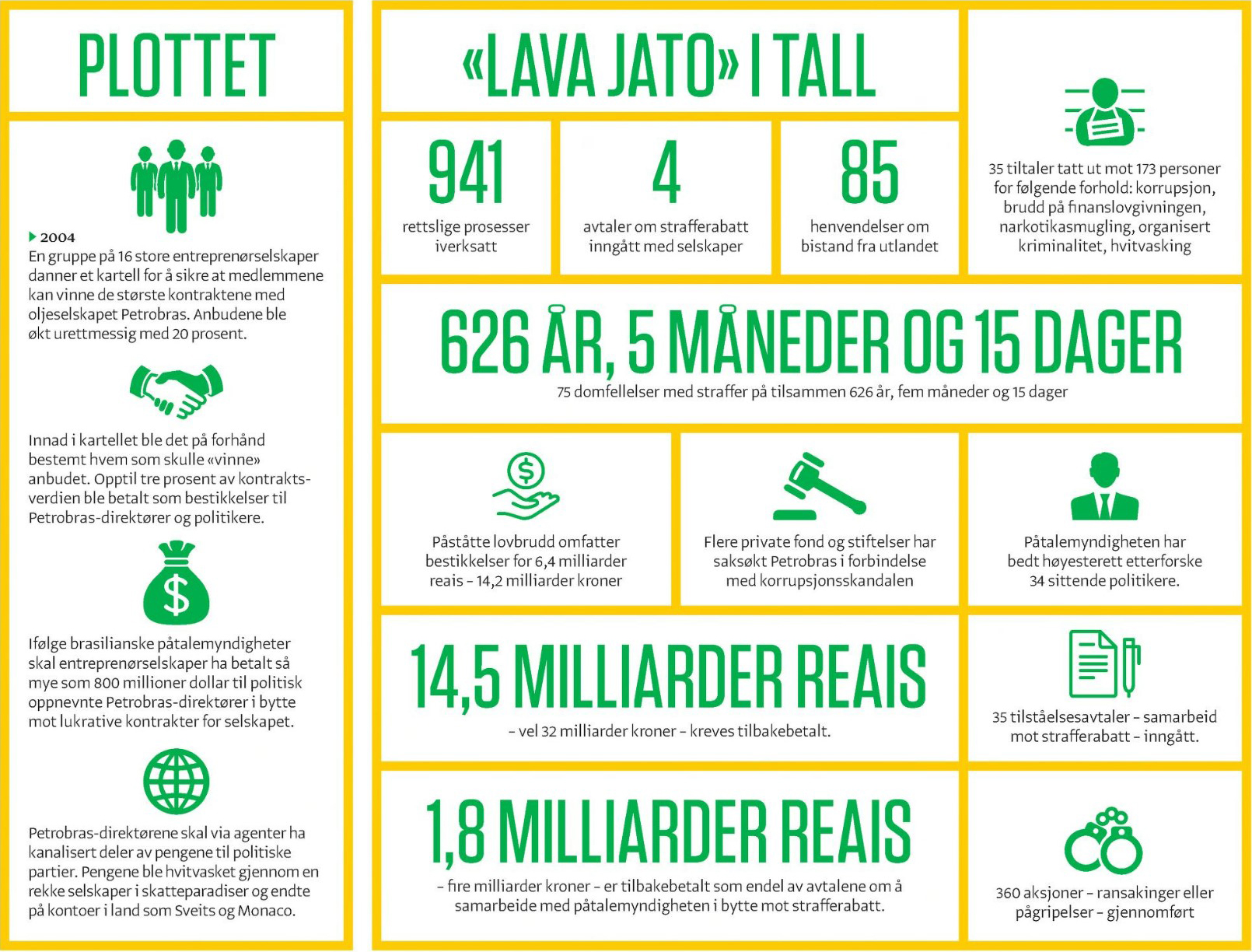

An additional problem arose in 2014, when a major corruption scandal in Petrobras was uncovered by Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava Jato). The case dated back to 2004, when 16 of the biggest construction firms formed a cartel to swindle Statoil’s partner in most of its Brazilian licences.

A total of 173 people were charged, with more than NOK 14 billion alleged to have been paid in bribes to politicians and corrupt Petrobras executives.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Statoil gransker alle Brasil-kontrakter”, E24, 30 December 2015. Jorge Zelada, former head of the company’s international division, was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment in 2016 for corruption and money laundering. The court found he had accepted a bribe in 2009 when he gave American company Vantage Drilling a contract worth almost NOK 16 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Petrobras-sjef dømt til tolv års fengsel i Brasil”, E24, 1 February 2016. Statoil initiated an internal investigation to determine whether it had been involved in the affair, but found no indications of this.

Rather than losing faith because of low oil prices and the corruption scandal, the group expanded its Brazilian operations and its collaboration with Petrobras became even closer. Because of Brazil’s huge resource base, the country was defined as one of Statoil’s core areas – with offshore fields where the group could exploit its expertise in subsea technology.

Gas and oil in the Campos basin

In 2006, Petrobras had proven enormous petroleum reservoirs in “pre-salt” formations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Pre-salt” refers to deposits older than an overlying stratigraphic package containing fairly thick and extensive salt deposits. The identification of this play opened the way to many discoveries and big petroleum resources. Pre-salt finds were initially made off Angola but, since the South American east coast Africa’s west coast mirror each other, the geology off Brazil is similar. These resources rapidly quadrupled Brazil’s estimated recoverable oil reserves and increased Norway’s interest in the country.

One of the licences where Statoil had acquired a holding back in 2005 was in 2 900 metres of water about 200 kilometres from land in block BM-C-33, part of the Campos basin. In 2010, Repsol Sinopec Brasil (RSB) proved large quantities of natural gas in a pre-salt play in this block. Dubbed Pão de Açúcar, the find is estimated to contain a billion barrels of oil equivalent in the form of gas as well as some oil and condensate. Two further discoveries were also made.

Equinor took over the operatorship of this ultra-deepwater licence in 2016. Together with partners RSB and Petrobras, it has developed a technical solution which is yet to be implemented. This involves a large FPSO to receive the wellstream from Pão de Açúcar, which ranks as the biggest of the fields, for separation into oil, gas and water.

After further processing, the oil will be exported by shuttle tanker and the gas piped to a Petrobras terminal on land for onward transmission to the domestic distribution network. Before development can start, however, the partners must be sure that Brazil offers a market for the gas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/no/news/202103-bm-c-33-brazil.html. Accessed 9 November 2021.

Another important asset in the Campos basin in Roncador, where Equinor acquired a 25 per cent holding in 2017. Petrobras retains the remaining 75 per cent. This field is special in that it has produced since the 1990s and long ranked as Brazil’s third largest producer. Discovered in 1996, it has been a money machine for Petrobras.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Equinor, 2017; https://onepetro.org/OTCONF/proceedings-abstract/98OTC/All-98OTC/OTC-8876-MS/45522.

The latter found it was advantageous to bring Equinor in as a partner, so that the Norwegians could apply the expertise in improved oil recovery (IOR) they have gained on the NCS to boost Roncador’s recovery factor by a further five to 10 per cent.

Bacalhau – Equinor’s biggest foreign field

One of Equinor’s largest Brazilian fields is Bacalhau in the Santos basin, which was proven in 2012. This oil and gas discovery ranked then as the largest made in Brazil after 2000, and was estimated to contain two billion barrels of high-quality light crude.

Bacalhau extends across two licences, and Equinor has secured interests across the field in two stages – first in 2016, when it secured a 66 per cent holding on the one licence for NOK 21.4 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Statoil gjør milliardkjøp i Brasil”, E24, 29 July 2016. The group and its partners then won an auction in 2017 to secure the other licence.

In the same year, the companies in the two licences entered into a unitisation agreement which made Equinor operator for developing the field and gave it a 40 per cent interest. ExxonMobil secured 40 per cent and Petrogal Brasil 20 per cent. State-owned Pré-sal Petróleo SA, which manages the production sharing agreement, is also a partner with no obligation to invest. Equinor CEO Eldar Sætre expressed great satisfaction: “Through this acquisition, we get access to a world-class discovery and strengthen our position in Brazil”.

Brazil was one of Statoil’s core areas, with substantial petroleum resources where the company could fully exploit its offshore expertise. Its importance was underlined when Sætre appointed Anders Opedal, who has broad operational experience, as country manager in 2017.

The development plan for Bacalhau was approved in March 2021 by Brazil’s National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP). As with the other deepwater fields, it featured subsea wells tied back to what will be the largest FPSO on the Brazilian continental shelf, with the capacity to produce 220 000 barrels of oil per day. This output would be loaded into shuttle tankers, with the gas injected back into the reservoir. Production is scheduled to begin in 2024.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Bacalhau blir Equinors største utenlandsfelt”, E24, 1 June 2021

Investment in the initial development phase for the field is put at NOK 72 billion. “Bacalhau will be the first development in the pre-salt area run by an international operator, [and] will create great value for Brazil, Equinor and its partners,” Arne Sigve Nylund, executive vice president for projects/drilling and procurement at Equinor, commented when the news became known.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Investeringsbeslutning for Bacalhau fase 1 i Brasil”, E24, 1 June 2021.

Oil and the environment

Equinor’s commitments in Brazil are among its most important foreign engagements, and involve participation in projects at all stages. They include mature fields producing crude as well as big oil and gas resources in deep water which are either under or awaiting development.

The group is also important for Brazil. With the Peregrino field, it became the country’s biggest international operator. And Petrobras, among others, has benefited from Equinor’s expertise in IOR and deepwater production.

But expanding petroleum production has its problematic aspects in Brazil, as elsewhere. The Brazilian government signed the Paris agreement in 2016, and committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 37 per cent in 2025 and 43 per cent in 2003 compared with the 2005 level. Nevertheless, a desire for economic growth and expectations of rising energy demand mean the government has signalled that it will accept a short-term increase in overall emissions from industry and energy production.

Brazil has not imposed taxes on CO2 emissions. Although local legislation permits gas flaring for safety reasons in order to safeguard normal production, Equinor does not do this routinely in either its Brazilian or its Norwegian operations.

The group is also pursuing clean energy in Brazil in the form of solar power, with the Apodi complex – operational in November 2018 – as its first such project. This renewable source has its drawbacks, too, in that it requires a lot of space, with Apodi covering the same area as 300 football pitches to accommodate 500 000 solar panels. The facility is operated by Norway’s ScatecSolar together with Brazilian partners.

Brazil and Argentina are the first two countries where Equinor is involved in developing and operating solar power farms. Plans call for it to participate in a number of such projects to produce clean energy for Brazil in coming years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor website, accessed 23 August 2021. These could make important contributions to reducing Brazilian greenhouse gas emissions in the longer term.

arrow_backMexico – brief affair in denationalised watersPetoro – the anonymous, little giantarrow_forward