An active state

An important political step had been taken after the Norwegian government received the initial approach from Phillips in 1962 seeking rights to explore for oil and gas on the country’s continental shelf (NCS). The Storting passed an Act on 21 June 1963 which established the state’s right to submarine natural resources. This doubled Norway’s area and marked the first step in preparing for a possible oil age.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1963-06-21-12 In the same year, the government issued permits to various big multinational oil companies for conducting geomagnetic and seismic surveys on the NCS. The data they acquired formed the basis for deciding where to apply for licences.

Companies involved in the Middle East, like Esso and Shell, were used to securing ownership of the oil when they were granted a concession for an area. That was not the way the Norwegian government wanted to do things. It could draw on experience from Norway’s hydropower developments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to avoid granting full control to powerful foreign companies.

First licensing round

When Norway’s first offshore licensing round was announced on 9 April 1965, it was based on regulations which built on the old hydropower concession laws. These secured the state’s rights to revenues and the ownership of the subterranean resources. Oil companies could seek permission to explore, develop and produce for a defined period. After that expired, the rights reverted to the state and the companies would have to reapply for them if necessary.

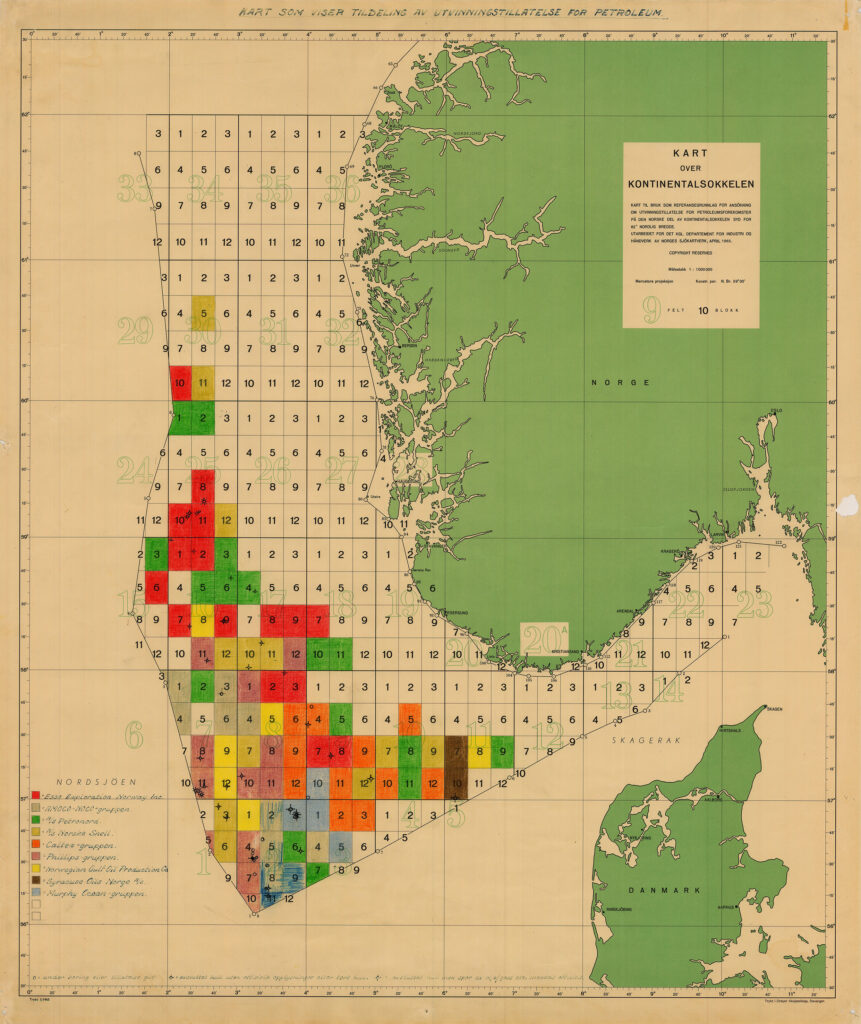

Before the first licensing round was announced, the southern part of the NCS was divided into a checkerboard of 314 blocks. The Norwegian Petroleum Council was established, with director general Jens Evensen at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as its chair, to follow up the award of acreage put on offer.

The Ministry of Industry initially awarded 78 production licences to eight individual or group applicants. Recipients included some of the world’s largest oil companies, such as Esso, Shell and Amoco. Phillips Petroleum, which had been the first to show an interest, secured blocks together with Fina and Agip as the Phillips group. Norway’s Norsk Hydro participated in the Petronord group with seven French partners, while Norwegian company Noco acquired licences alongside Amoco in the Amoco-Noco group.

In order to administer the growing level of activity, the industry ministry established a separate oil office in 1966. This was initially only a temporary creation, in case nothing was found on the NCS.

First Cod – then Ekofisk

Esso became the first to “spud” (start drilling) a well in the seabed during July 1966, and the first to discover traces of oil in what later became known as the Balder field. Phillips struck oil in the Cod field in 1968. But these discoveries were small, and so many “dry” wells were being drilled that the oil companies began to lose faith in the NCS. Several of them began closing their offices and sending people home in the spring of 1969.

Nevertheless, continued hopes of finding oil meant the government had to be prepared for that eventuality. If commercial quantities of oil were discovered, “staffing of the [oil] office must be substantially strengthened”, White Paper no 95 for 1969-70 stated. “In that case, it could be relevant to establish a separate directorate for continental shelf issues, possibly also a state oil company to handle the government’s commercial interests in petroleum production.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 95 to the Storting for 1969-70. That resembled a plan.

These words suddenly became relevant. No sooner had the White Paper been submitted than oil was discovered in Ekofisk.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/home/ Engineer Olav K Christiansen in the industry ministry’s oil office was notified of the find on 23 December 1969, and he and his small band of colleagues had their hands full the following spring.

Instead of being concerned about which oil companies were going to pull out, the office received a string of requests for consent to drill more wells. The result was great activity and several more discoveries.

Conservative Party politician Sverre Walter Rostoft was industry minister at the time in the non-socialist coalition led by Per Borten from the Centre Party. He told the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) on 9 September 1970 that oil “may mean a very great deal, it could actually initiate a completely new era for Norway. […] We must expect new discoveries. […] That will create some new companies, but first and foremost provide work for existing industry.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK schools broadcasting, 9 September 1970.