In Canada’s deep forests

The year 2007 proved a memorable time in Statoil’s history. The company merged in December with Norsk Hydro’s oil and energy division, making it even more dominant on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). StatoilHydro, as the company was called until it reverted to Statoil in 2009, also became a player to be reckoned with on the world stage. Earlier in the year, CEO Helge Lund had launched a giant international investment campaign which staked out a completely new course for the company. It paid more than USD 2 billion to acquire all the shares in Canada’s North American Oil Sands Corporation (NAOSC) – an important purchase in StatoilHydro’s global growth strategy. “We’re also developing our global heavy crude portfolio and strengthening our market position in North America,” Lund stated in a statement.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 27 April 2007, “Statoil kjøper i Canada”.

In response to critics of the oil sands involvement, he said: “These are resources which will be developed regardless”. He also maintained that the company would produce this petroleum source in a cleaner and less energy-intensive way than anyone else.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet, 7 September 2009, “Norge har investert milliarder i utvinning av oljesand”.

StatoilHydro’s annual report for 2007 proudly presented two very different businesses in Canada – oil offshore and heavy crude in the forests.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro. In 2007, the company had interests in producing fields in Canada, the Gulf of Mexico, Venezuela, Algeria, Libya, Angola, Azerbaijan, the UK, China and Russia, while major development projects were also under way in Brazil, Nigeria and Ireland. The Hydro part of the merged company had already been present in Canada for a decade and was making good money from production off Newfoundland. While the heavy crude commitment lasted only nine years, the offshore commitment has continued.

Oil sands in Alberta

Petroleum plays a large role in the Canadian province of Alberta. The economy of both government and individuals, expressed by such parameters as house prices and unemployment, fluctuates in line with oil prices.

Statoil opened an office in one of Calgary’s skyscrapers in 2007. A small Norwegian “colony” emerged and the Sons of Norway association for immigrant descendants experienced a sharp upturn. Within a few years, the company’s magenta logo was highly visible in local advertising campaigns.

The actual oil-sand licences lay 300 kilometres to the north and covered 1 110 square kilometres in the Athabasca region, north-east of the provincial capital of Edmonton. Recoverable oil reserves were put at about 2.2 billion barrels.

One reason why Statoil opted for a commitment to Canada’s oil sands was its heavy-crude experience from Venezuela. The relatively stable tax regime in Alberta was another advantage. Canada is also next door to the world’s largest consumer market for petroleum products, which would safeguard sales.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

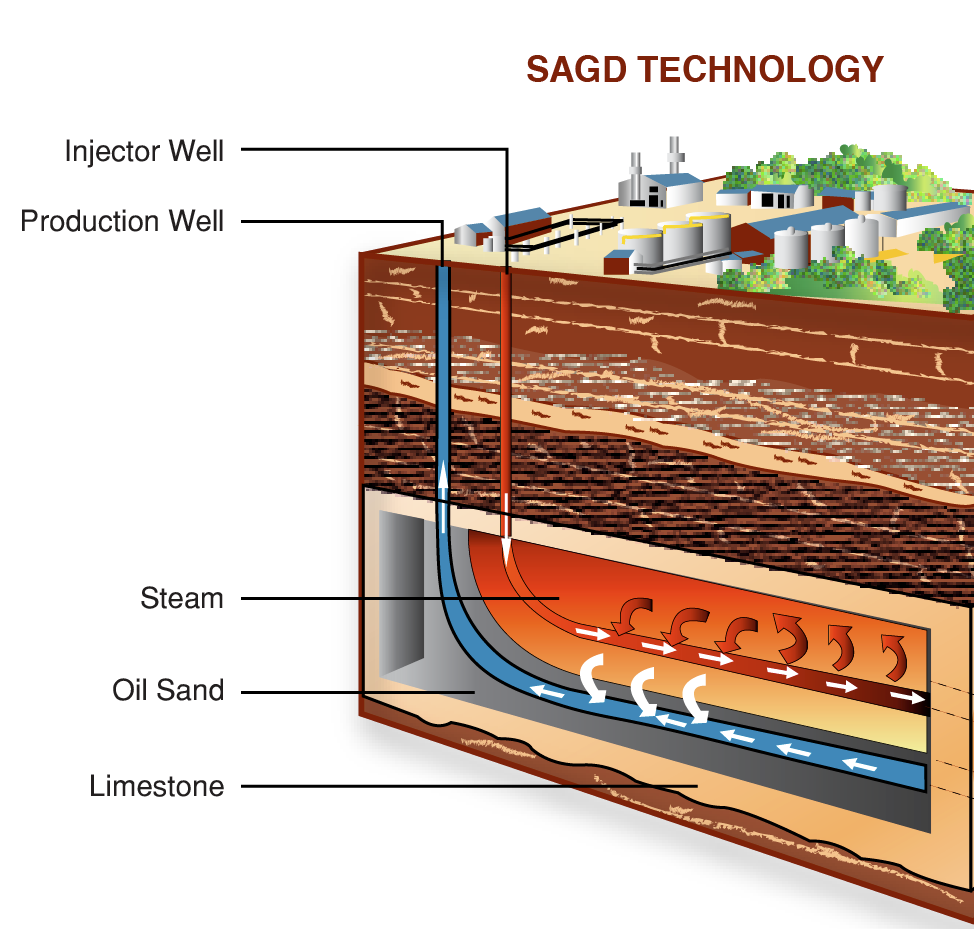

The first step was to launch the Leismer demonstration project for a process called steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD). Steam injection began on 3 September 2010 and production on 27 January 2011. That was followed by the start-up of the commercial project, Kai Kos Dehseh, with a gradual build-up of production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: While the trial project produced roughly 20 000 barrels of heavy crude per day, total daily output from the three licence areas was expected to reach 200 000 barrels by the late 2020s. Aftenposten, 27 April 2007, “Statoil kjøper i Canada”.

Production technology and green challenges

Oil sands, also known as tar sands or bitumen, are a black, viscous hydrocarbon deposit. Much of their exploitation in Canada had been based on excavating opencast pits. That created big scars on the landscape, while waste products were stored in huge basins which polluted rivers and harmed both animals and people. Statoil was accordingly criticised from the start for engaging in this type of production by environmental activists, with Greenpeace in the lead. A representative of the latter attended the annual general meeting every year as a shareholder and protested about the project from the podium.

Statoil’s management nevertheless believed that it could recover oil from the sands in a more responsible manner than was normal in the industry. The company did not intend to use opencast methods. Instead, SAGD involved pumping steam into the sub-surface to drive out the oil in an effective way. A great many pairs of horizontal wells were driven into the bitumen-bearing formation. Steam from a dedicated plant was then pumped into the uppermost well in each pair. On condensing, the steam liquefied the bitumen or viscous oil in the sands. The resulting mix of water and warm bitumen flowed into the lower well and could be pumped to surface for separation. Once the heavy oil had been removed, the water was treated and returned to the steam plant.

Although the SAGD method was far more environment-friendly than opencast extraction, its water consumption, the large amount of space required and CO2 emissions presented environmental challenges.

Where the supply of water was concerned, Statoil intended to take this in the form of brine from a deep formation rather than the Athabasca river. Ninety per cent of it would be reused. The company’s aim was to achieve almost full recycling. In a bid to reduce water consumption, it intended to try injecting solvents to enhance steam effectiveness.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro.

CO2 emissions from producing oil sands were higher than with conventional oil output. That was because the boilers used to produce steam were heated by burning natural gas. This required a lot of energy and released a great deal of CO2.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Oil sands production released 60 kilograms of CO2 per barrel – 100 times more than emissions from the Johan Sverdrup field in the North Sea.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) offered another option for reducing the problem, and the Albertan government had ambitions of accomplishing this. Its goal was to capture 139 million tonnes of CO2 per annum by 2050. Statoil entered into a collaboration with other industrial players and the government of Alberta to meet that objective. Among other moves, the company established a technology centre for heavy oil in the province – its first such centre outside Norway.

Indigenous peoples and green opposition

Many groups of indigenous Canadians lived in the areas where oil sands production was being pursued. The Chipewyan Dene occupied the area where Statoil secured licences, and Kai Kos Dehseh – Red River Flowing – is their name for the river flowing through it. The official English name is the Christina River.

To build a good collaboration with the locals, Statoil established a separate post of community relations manager and a trainee programme to ensure recruitment of local personnel. The company’s slogan was “being a good neighbour”. According to the community relations manager, the project depended on maintaining a good interaction with the indigenous population. That would be the essential for a positive growth story in Canada.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro.

Although the intentions were good, oil sands production created complex problems which could not be easily overcome. In Norway, newspapers such as Oslo daily Dagbladet wrote in 2009 that the oil sands business increased cancers in the indigenous population. High values for arsenic and mercury were identified in the rivers. The incidence of cancer in Fort Chipewyan, a village downstream from the oil sands area, was 30 per cent higher than normal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet, 20 May 2009, “Kreftboom i oljesand-området”. Opposition to the project increased.

In February 2011, the Albertan government took Statoil to court, charged with committing environmental crimes in connection with winter drilling and roadbuilding. It was alleged that river water was used to ice the roads in the area so that they could support the transport of equipment, and that water was being used illegally in production. Statoil was accused of 19 breaches of the water legislation and risked a fine of more than NOK 60 million.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), 6 April 2011, “Urfolk føler seg forbigått”. After the company admitted a failure to comply fully with its water permit in 2008-09, the court imposed a far milder penalty. It had to clean up its act and produce an e-learning programme on water extraction worth just over NOK 1 million.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, 1 November 2011, “Statoil slapp billig i oljesand-saken i Canada”.

For its part, Statoil maintained that it had nothing to apologise for with regard to informing local interests, including indigenous peoples. Through consultative committees, the company gave groups affected by its operations the opportunity to discuss the development plans critically so that the improvements could be made to the way the project was being implemented.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor website. “Statoil-Supplemental%20Information.pdf”

Lack of clarity, retreat and losses

No sooner had the demonstration project come on stream in 2011 than Statoil sold 40 per cent of Kai Kos Dehseh to Thailand’s PTTEP for USD 2.3 billion. The partners then shelved the plans to develop further phases after the pilot stage.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 18 December 2016, “Det har vært et katastrofeprosjekt for Statoil”.

It was no longer easy to determine how much Statoil had made or lost on its foreign engagements. After the Hydro merger, the company under Lund had made the financial statements in its annual report less simple to follow. The Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway delivered unusually stinging criticism in 2014 of Statoil’s accounting methods for 2012. The company’s international upstream activities were reported collectively, so that results for individual countries no longer appeared. The Financial Supervisory Authority recommended that development and production in North America should be presented separately, which Statoil was unwilling to do.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.finanstilsynet.no/nyhetsarkiv/pressemeldinger/2014/kontroll-av-finansiell-rapportering–statoil-asa/; https://www.equinor.com/news/archive/2014/03/11/11Marreviewfinancialreporting.

What the annual reports did present clearly was the development in the share price and dividends paid.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2081, StatoilHydro. Lund’s reputation was high at this time. During his period as CEO, the value of the company had risen from NOK 189 billion to roughly NOK 500 billion. From January to September 2014 alone, the share price rose by 23 per cent to reach a record high. A few weeks later, Lund announced that he was resigning – at a peak.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lars West Johnsen, Dagsavisen, 16 May 2020, “Da vikingene oppdaget Amerika”. His reputation subsequently took a substantial dive as the size of the losses incurred from the North American commitment became clear.

As early as 2015, the Statoil management admitted that the oil sands “dream” in Canada was more like a “nightmare”. John Knight, who was in charge of strategy, said: “Had we known then what we know today, I think we probably wouldn’t have become involved in the project”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 19 January 2015, “Ville ikke satset på oljesand i dag”. The company was then in the process of developing a more aggressive climate strategy, and the time had come for a retreat from the oil sands.

Statoil and PTTEP reached agreement in 2014 on a swap in the Kai Kos Dehseh licences, which gave the Thai company USD 200 million and sole rights to three areas. A write-down of NOK 8 million was booked by Statoil.

The company then sold Leismer and Corner, its two wholly owned development projects, to the Athabasca Oil Corporation for a total of NOK 5.4 billion – resulting in a further write-down of roughly NOK 4.5 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 15 December 2016, “Statoils oljesandsatsing begraves – med mye milliard tap”. The known accounting looses at 31 December 2016 amounted to at least NOK 13 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nettavisen, 29 December 2020, “Equinor i oljesand-trøbbel i Canada: Kan få ny regning på 3,3 milliarder kroner”.

Under its new CEO, Eldar Sætre, Statoil decided it was better to accept the losses than suffer further reputational damage. It was not worth participating in what National Geographic had called “the world’s most destructive oil operation”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Alberta, Canada’s oil sands is the world’s most destructive oil operation—and it’s growing (nationalgeographic.com), 11 April 2019.

Lars Christian Bacher, Statoil’s executive vice president for international development and production, commented on the sell-off in economist-speak: “This transaction is in line with Statoil’s strategy of portfolio optimisation in order to strengthen our financial flexibility and invest in our core areas globally, including off the coast of Newfoundland.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 15 December 2016, “Statoils oljesandsatsing begraves – med mye milliard tap”.

Out of oil sands completely

Despite its new climate strategy and change of name, Equinor retained interests in the Athabasca Oil Corporation, which is still pursuing oil sands development. These shares were part of the settlement when the company sold out of the business in 2016.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NTB, 25 August 2018, “Equinor har fortsatt milliardinvestering i oljesandselskap”. All of them were sold in January 2021, thereby cutting Equinor’s last ties with oil sands production in Canada.[REMOVE]Fotnote: E24, 21 January 2021, “Equinor kuttar siste band til kontroversiell oljeutvinning”.

But the final bill had yet to be paid. Problems remained with the company’s earlier ownership in Alberta. A dispute flared up with the Canadian government in 2020, with the tax authorities seeking to establish what had transpired when Statoil sold out of 40 per cent in Kai Kos Dehseh in 2014. At issue were the division of assets and deductions in a Canadian transaction, which had not been adequately clarified. In its interim report for the third quarter of 2020, Equinor wrote that the dispute could end in a court case lasting several years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nettavisen, 29 October 2020, “Equinor i oljesand-trøbbel i Canada: Kan få ny regning på 3,3 milliarder kroner”.

It remains unclear how much Equinor has lost from its oil sands commitment in Canada’s deep forests. This has also been overshadowed by the deficit on the big US involvement in Lund’s time.

arrow_backAmbition for a “moon landing”Off Canada’s east coastarrow_forward