Up and down with US shale

The USA is one of the world’s oldest oil producers, but output had been in decline since the 1970s. That left the Americans, as big petroleum consumers, dependent on imports. In 2005, the USA bought 60 per cent of all the oil it used from abroad. It came as a surprise to many that new technology for recovering oil and gas from impermeable shales (and oil from strata with low permeability) could increase production so much that the country became virtually self-sufficient within a few years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, “Skiferoljerevolusjon er den største overraskelsen i oljehistorien”, 22 May 2014.

Hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) is the key here. This means injecting primarily water, sand and chemicals below ground to fracture shale or “tight” rocks, with limited permeability, so that the oil and gas they contain can flow out.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hans Jakob Hegge, US country manager for Equinor in 2018-20 responds to criticism of hydraulic fracturing in the USA, 9 December 2020, Equinor website, accessed 15 November 2012.

Once the new method achieved profitability, the USA again became one of the world’s largest oil and gas producers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.norway.no/no/missions/oecd-unesco/norge-oecd-unesco/nyheter-arr/nyheter/ieas-nye-publikasjon-energy-policies-of-iea-countries-united-states-2019-review/ A new oil boom occurred which many – including Statoil – wanted to be part of.

Why the USA?

Once Statoil had been given a freer rein as a listed company in 2001 and subsequently merged with Norsk Hydro’s oil and energy division in 2007, it had stronger muscles for making an international commitment.

A tradition had developed in Statoil for establishing itself in countries with rich petroleum resources and a national oil company, and for participating along the whole value chain. But StatoilHydro believed, under Lund’s leadership, that the time had come to act more effectively to increase reserves and production. By acquiring stakes or taking over established oil companies in countries like the USA, the company would avoid the time-consuming build-up phase with petroleum fields and get a quicker return on its investment. The downside was that, in a time when oil prices were high, resources were in big demand and their cost had shot up.

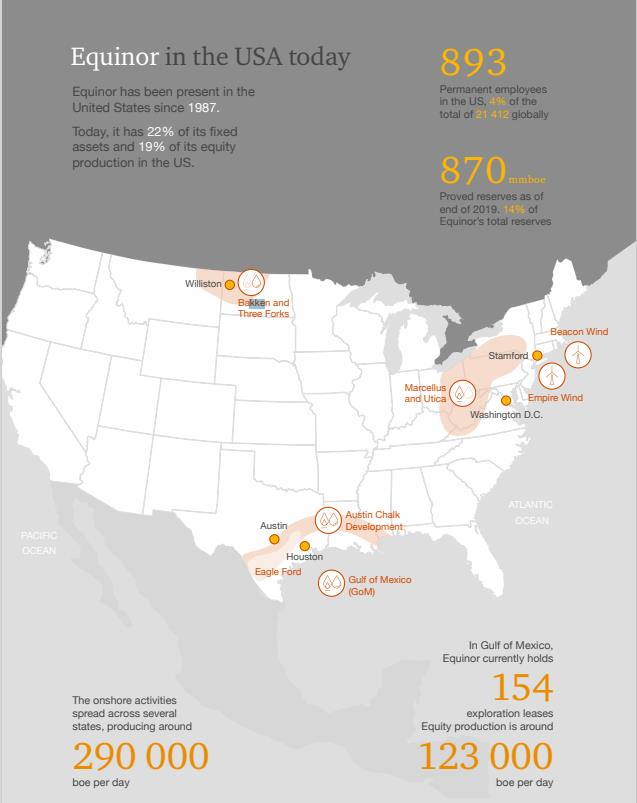

The ambition in North America was to develop a substantial and profitable position, both in deepwater areas of the Gulf of Mexico and in “unconventional” US shale oil and gas and Canadian oil sands.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2012, Statoil.

A clearer picture of the emphasis on unconventional resources is provided by Statoil’s annual report for 2011. Among other moves, the company had established business areas for global strategy and business development, led by John Knight from London, and development and production North America under Bill Maloney in Houston.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2012, Statoil. The foreign commitment, particularly in the USA and Canada, had clearly become important. With offices geographically located in Britain and Texas, day-to-day operation of these units was not under the same tight control from head office in Stavanger as before.

Appalachian shale gas

A strategy based on company acquisitions was well suited to countries such as the USA and Canada, where this was a normal approach to growth in the business world. Since Statoil knew little about the onshore oil industry, it allied with more experienced operators in this area. In November 2008, StatoilHydro acquired 32.5 per cent of the shares in Chesapeake Energy Corporation, a US specialist in recovering shale gas, for USD 3.3 billion. This brought the company into the Marcellus shale area in the Appalachian basin of the north-eastern USA. Statoil became Marcellus operator in 2012 and simultaneously farmed into further acreage in West Virginia and Ohio. This area came to account for a substantial part of the company’s US production.

Texan shale oil

Statoil’s next onshore acquisition in the USA involved acquiring acreage in the Eagle Ford shale formation in south-west Texas from Enduring Resources. This 2010 transaction, made jointly with Talisman Energy USA (later owned by Repsol), cost USD 0.9 billion. Statoil became operator for 50 per cent of the acreage owned with Talisman in 2013, and then increased its interest to 63 per cent in 2015 and took over the full operatorship. It then had an acreage of about 2 800 hectares.

Bakken shale oil

The company secured its third shale oil area in December 2011 by acquiring Brigham Exploration Company for USD 4.7 billion. Making money from this investment depended on increasing output rapidly, improving productivity and having an oil price of more than USD 100 per barrel. Brigham was the riskiest of Statoil’s three shale oil projects.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten 2022. En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001. Universitetsforlaget, s. 231 og 234 ff. Just how hazardous was first revealed a couple of years later.

This acquisition gave the company a stake in North Dakota’s Bakken area, where the oil is contained in tight formations which can also be produced by fracking. At 31 December 2017, it held about 9 500 hectares in Bakken and the nearby Three Forks shale oil formation. Statoil was operator for the acreage with a holding of about 70 per cent.

Production took place from such large areas because the resource density is not as high as in conventional petroleum reservoirs. Development was therefore decentralised, with many wells and extensive subsurface piping system. In many cases, wells came close to homes, farms and other buildings – which could create conflicts.

Downscaling in gas

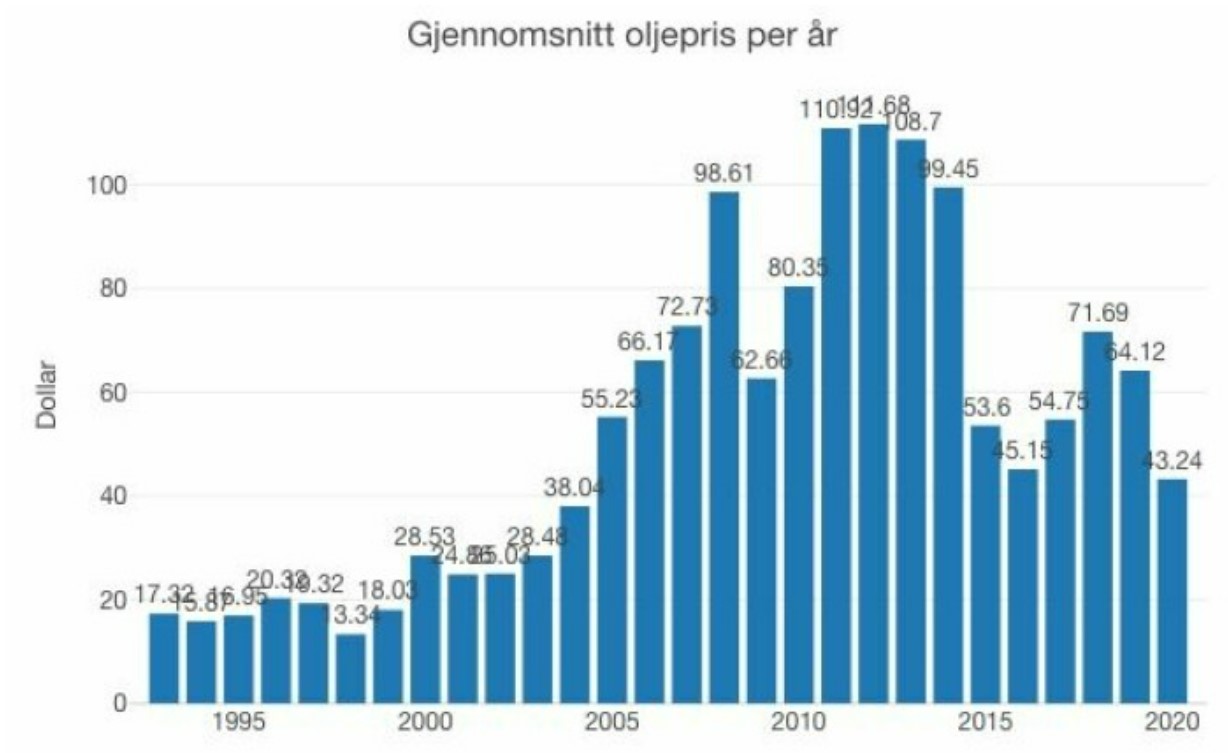

The bulk of the acquisitions in the USA were made in a boom time, with some of the highest oil prices ever – between USD 80 and USD 110 per barrel. That meant production from the US fields on land could be sold at good rates – as long as it lasted. But oil prices sank dramatically in the autumn of 2014 and during 2015, and were down to USD 30 per barrel at their lowest. That level persisted until 2018.

Oil prices fall when supply exceeds demand, and the growth in output globally was primarily the result of US shale oil production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, op.cit. The slump caused big losses for Statoil, especially in the USA and particularly onshore. It was not alone – other shale oil/gas producers also suffered.

Warning lights were now beginning to blink properly. It was clear that Statoil, where Eldar Sætre had taken over as CEO, needed to retrench in the USA. Torgrim Reitan, who had been CFO in 2011-15, was put in charge of the US business. The company began to divest, but Reitan downscaled and coordinated the organisation for the three fields with the aim of making money from onshore operations in America at a price of USD 50 per barrel.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten 2022: 243.

The first disposal occurred in 2016, when Statoil sold Marcellus interests in West Virginia to EQT Corporation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Statoil, Statoil divests assets in the Marcellus, 2 May 2016. Some of the partner-operated assets in the same state were also sold to Antero Resources Corporation. According to Reitan, the US business remained one of the priority areas in the company’s international strategy. America accounted in 2016 for 14 per cent of Statoil’s total equity output and held an important place in its production outside Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Statoil, Statoil fortsetter å optimalisere sin landbaserte portefølje i USA, 1 August 2016.

Statoil was operator for two formations in the Appalachian Basin in Ohio, producing gaseous and liquefied natural gas, and acquired additional interests in the area from the Northwood Energy Corporation in 2017. That raised its total acreage to about 10 300 hectares.

Out of shale oil on green grounds

The next sale occurred in 2019, when Equinor disposed of its whole 63 per cent holding in the Eagle Ford shale oil area in Texas to Repsol, which also took over the operatorship.

At that time, more than a decade had passed since the company developed its first environmental and climate strategy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2008, Statoil: 10. Basing operations on its provisions had become even more urgent following the Paris agreement in 2015. Equinor wanted to reduce its own production from shale oil and oil sands, which contributed to a poor reputation because of the large amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs) released. Between 2016 and 2021, Statoil/Equinor gradually divested its holdings in Canadian oil sands and Venezuelan heavy crude – although not Argentinian shale oil.

Senior management maintained that the US remained a core area for Equinor. But it said the company would concentrate on offshore in the Gulf of Mexico and the Empire Wind project off New York, and less on shale oil and gas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, Equinor sells Eagle Ford asset, 7 November 2019.

In 2020, Equinor sill had interests in the Bakken shale oil area of North Dakota and Montana. But the recovery technique utilised came in for criticism in the Norwegian media. The company responded that shale oil and gas production had political support in the USA, and provided energy, revenues and jobs. It also claimed that this output reduced GHG emissions by outcompeting coal. Country manager Hans Jakob Hegge understood that a number of landowners were worried that the chemicals used could pollute the groundwater, but asserted that these substances were employed only in closed processes and handled in line with requirements and guidelines set by local and federal authorities. Equinor said that no incidents had been experienced where chemicals and other products polluted groundwater sources.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hans Jakob Hegge, op.cit.

Although oil recovery in the Bakken area was conducted in accordance with legislation and regulations, it nevertheless did not represent the most environment-friendly way to pursue production. Nor did profitability meet expectations, according to Anders Opedal, Sætre’s successor as CEO. In 2021, Equinor sold its Bakken holdings to Grayson Mill Energy for about USD 900 million. The company preferred to deploy the money towards more competitive assets in its portfolio and thereby create higher value for its shareholders, Opedal said.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, Equinor sells its US onshore assets in the Bakken, 10 February 2021. The divestment was also probably a result of reputational knock Equinor had suffered the year before, when its land-based operations had been described in the media as Norway’s biggest industrial scandal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Norges største industriskandale”, 7 May 2020.

NOK 80 billion lost

Oslo business daily Dagens Næringsliv published a big story in May 2020 headlined “The secret Equinor reports”, which presented a biting criticism of the money spent by the company on its US commitments. Although the write-downs of American assets had been published in Equinor’s annual reports, it was only with this story that the general public and the politicians discovered the amounts involved – a loss of NOK 200 billion. That figure included both onshore and offshore US commitments in recent years. As if that were not enough, the paper revealed rampant extravagance and negative behaviour which shocked most people. Numerous and gross examples were cited.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “De hemmelige Equinor-rapportene,” 9 May 2020.

Nevertheless, these figures were not new within the company. Its internal audit function had submitted a financial compliance verification report for US onshore on 10 October 2014 – four days after Lund had notified the board that he had accepted a new job as CEO for Britain’s BG.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Sætre, his successor, had been a member of the top management for many years, and was therefore not unfamiliar with the problems. It became his job to take action. As mentioned above, Reitan was charged with cleaning up the chaos – with invoices for hundreds of millions of dollars which had not been chased up, invoices paid too late or twice, excessive credit card spending and equipment which had disappeared. The fact that oil prices slumped to a low point in 2015 and remained there made the problems even bigger and harder to deal with. Belts were tightened across the whole company, and not just in the USA.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The Dagens Næringsliv stories, all the media attention which followed, and demands for an explanation from the minister of petroleum and energy, prompted the Equinor board to appoint a committee chaired by chartered accountant Eli Moe-Helgesen from PwC to review the company’s US business with particular attention to onshore operations.

It concluded that the big financial losses on investments in the USA were driven by an ambitious growth strategy which failed to take adequate account of the risk picture for the business. Insufficient attention was paid to value creation and control. The management had limited experience of land-based operations in the USA, and continuity was lacking in key roles. That had a negative impact on the company’s follow-up and operation of the business.

Onshore acquisitions in the USA were based on excessively optimistic price expectations, which failed to hold good when prices fell from 2014. That resulted in big losses, and write-downs of USD 9.2 billion (about NOK 80 billion) in the land-based business up to 31 December 2019.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, Offentliggjøring av rapport om Equinors virksomhet i USA, 9 October, 2020. The remaining loss related to exploration activities and was partly linked to offshore operations in the Gulf of Mexico as well as conditions associated with gas exports (see table).

| Net impairments US onshore | 9.2 billion USD |

| Net impairments US offshore (Gulf of Mexico) | 4.0 billion USD |

| Net impairments MMP segment | 0.5 billion USD |

| Unsuccessful exploration activity (Gulf of Mexico) | 4.0 billion USD |

| Losses on commercial contracts (mainly Cove Point LNG terminal) | 1.3 billion USD |

| Internal financing costs | 2.4 billion USD |

| Contribution from operating activities | 0.1 billion USD |

| Total (net loss per 2019) | 21.5 billion USD |

[REMOVE]Fotnote: PwC-rapport: «Equinor in the USA. Review of Equinor’s US onshore activities and learnings for the future. Prepared for Equinor ASA’s Board of Directors 9 October 2020»: 28

During a public hearing in the Storting (parliament), Lund also expressed self-criticism.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting, hearing by the standing committee on energy and the environment on the report by the minister of petroleum and energy on Equinor ASA’s activities in the USA and the government’s owner follow-up (Report no 8 (2019-2020)), 3 November 2020. He admitted that Statoil under his leadership had underestimated the complexity of operating the countless wells on land and how much follow-up in terms of accounting and control was required in the support systems.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nrk.no/norge/helge-lund-om-pengeslosingen_-_-jeg-ergrer-meg-na-i-ettertid-at-vi-ikke-sa-det-tidligere-1.15068294.

Sætre characterised the report as “tough reading for many people. We made investments which were not robust when the market reversed, and we should have identified the control challenges in the land-based business earlier.” He believed the company should learn from this and ensure that it did not get into in the same position again.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Press release, Equinor, Offentliggjøring av rapport om Equinors virksomhet i USA, op.cit.

Expensive lesson

Equinor’s US “adventure” provides clear evidence that its foreign commitments have not been uniformly successful. That applies particularly to the involvement with unconventional energy sources on land. With hindsight, it is easy to see that the company’s ambitions exceeded its expertise in a market where oil prices fluctuate up and down. Most attention has been focused on the onshore business, but it is worth bearing in mind that Equinor in reality lost nearly as much money on its offshore operations in the US Gulf of Mexico even though that is where the company had its greatest technological experience and leading-edge expertise.

The energy-intensive production of shale oil and gas in the USA has been partly divested. Equinor is continuing to apply its core expertise in deepwater operations. A commitment is also being made to offshore wind power as a new business area, and a similar strategy is being pursued in other countries where Equinor is involved. That can surely be considered an important lesson for a company which wants to be sustainable not only financially but also environmentally.