Offshore Colombia

Statoil had a relatively long history in South America. It had been producing heavy crude in Colombia’s neighbour, Venezuela, since the late 1990s, and was also heavily involved in both oil and gas production off Brazil.

Legal and illegal

Oil has been Colombia’s most important legal export commodity, primarily to the USA. Traditionally, its economy has been based on agriculture – including the export of coffee and bananas. A more questionable side of the country is that it ranks as a major producer and exporter of cocaine.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.fn.no/Land/colombia. That activity has contributed to 50 years of armed conflict between guerrilla groups, the army, right-wing paramilitaries and drug cartels. Negotiations began in 2010 between president Juan Manuel Santos and the Farc guerrillas, and a peace agreement was signed in September 2016.

Santos, who held the presidency from 2010 to 2018, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016 for his work on this peace deal, where he had been assisted by Norwegian diplomats.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Manuel_Santos Unfortunately, the agreement failed to win ratification in a referendum.

Foreign investment increased after the Colombian government took steps during the 2000s to improve security in the towns. Free trade agreements were signed with the USA, the EU and China.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.fn.no/Land/colombia.

Statoil explores offshore

Ecopetrol, owned 80 per cent by the Colombian state with private investors holding the rest, was the dominant oil company in the country. All its directors were appointed by the president, and he decided in reality which companies should be awarded production licences.

So it is likely that Santos himself was involved in allowing Statoil to farm into licences in the country.

Like a number of the exploration targets where the company was involved internationally, the deepwater areas off Colombia were almost virgin territory. “We are gaining access to a vast underexplored frontier area through early access at scale, which is in line with Statoil’s exploration strategy,” Nick Maden, senior vice president for exploration activities in the western hemisphere, observed in a press release when a first licence was secured in Colombia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: E-24, 24 July 2014, “Duket for Statoil-debut i Colombia”.

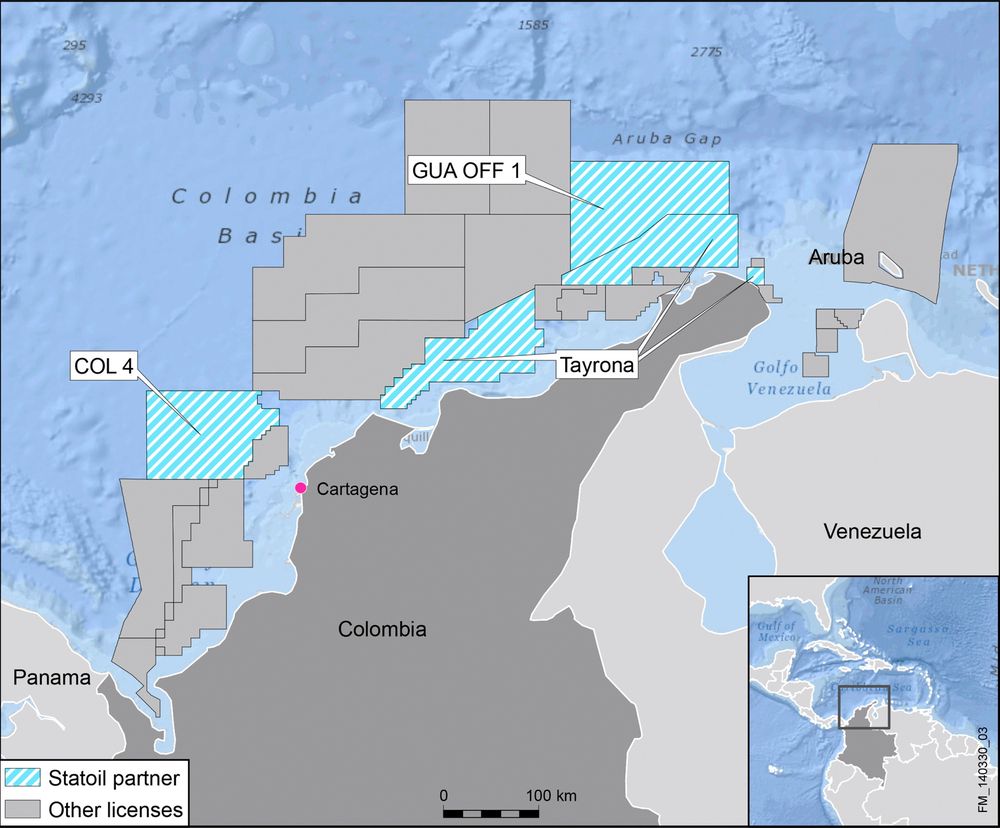

Awarded in July 2014, this holding was in deepwater licence COL4. Spain’s Repsol was the operator, while Statoil had a 33.33 per cent interest.

Two months later, the company could announce that it had farmed into two more licences by buying holdings from Repsol. This involved 10 per cent of the Tayrona licence operated by Brazil’s Petrobras and 20 per cent in Guajira Offshore 1, where Repsol was the operator (see map).

All these licences committed the companies to acquire seismic data, but they were not obliged to drill. All the transactions otherwise had to be approved by the National Hydrocarbons Agency of Colombia (ANH).[REMOVE]Fotnote: E-24, 24 July 2014, “Statoil sikrer nytt leteareal i Colombia”.

Statoil established a separate subsidiary in the Netherlands to run the involvement in Colombia. This paid tax to the country and invested a good deal in exploration during 2016-17.

Pulling back

In 2020, the exploration work which Statoil/Equinor had committed to was nearing completion. The subsidiary responsible for this activity no longer had any personnel. No results worth continuing with had been achieved. The subsidiary’s equity was negative at USD 121 million, which represented the funds it had devoted to exploration.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2020, Equinor: 308. It was time to withdraw. This fitted with Equinor’s revised exploration strategy, which replaced a broad commitment and working in many countries simultaneously with concentrating on fewer core areas. Colombia no longer featured on that list in South and Central America. Instead, the company chose to concentrate on Brazil and withdrew from Venezuela, Uruguay, Nicaragua and to some extent Argentina as well as Colombia. From being involved in about 30 countries around the world in 2014, Equinor remained active in roughly 15 by 2021.