Statoil’s Iranian adventure

Iran is second only to Saudi Arabia for its oil and gas reserves. It occupies a strategic position, bordering Pakistan and Afghanistan in the east, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Armenia to the north, and Turkey and Iraq in the west. It also has coastlines on the Arabian Gulf and Gulf of Oman to the south and the Caspian in the north. Although most of the country comprises a high plateau with deserts and steppes surrounded by tall mountains, petroleum has made it rich – and a major regional power.

The first oil was proven in Persia, as Iran was then known, by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) in 1908. These strategically important resources were crucial for Britain’s fighting capacity in both World Wars, but UK control ended when Iran nationalised its oil in 1951. Two years later, the USA and Britain planned and supported a coup against the first democratically elected prime minister, Muhammed Mossadeq, and the USA-friendly Shah Muhammed Reza Phavlavi took power.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.fn.no/Konflikter/Asia/iran The USA was Iran’s most important trading partner until 1979, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini gained power. Since then, the country has been subject to trade sanctions by the USA and other western countries on various occasions, particularly because of its nuclear programme. China, India, South Korea and Japan have taken over as the most important importers of Iranian oil and natural gas.

Development operator

After Khomeini died in 1989, Ali Khamenei took over as supreme leader and Ali Akbar Rafsanjani replaced him as president. Since Iran needed technology and capital, the latter allowed the foreign oil companies to return.

In 1999, Statoil had feelers out to establish itself in the petroleum-rich nation. Although the collaboration with BP which had taken the company into many other countries had ended, CEO Olav Fjell wanted to maintain involvements outside Norway. “An international effort will be maintained, but concentrated on a limited number of resource-rich oil and gas provinces,” he wrote in the group’s 1999 annual report.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1999, Statoil: 6. The following year, he headhunted Briton Richard John Hubbard from BP to lead this work.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), 12 September 2003, “Statoil-direktør går av”.

Initially, results in Iran appeared promising. Statoil’s visiting representatives were well received. Meetings were held in both Tehran and Ahwaz, with an excursion to view Iran’s cultural treasures in Isfahan. Iranian oil minister Bijan Zanganeh was regarded as a good friend of the company. Nevertheless, it took time before the talks yielded results. Meetings were held in the government guest house in Tehran with state oil company NIOC about the Zagros improved oil recovery (IOR) project in Ahwaz.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ole Johan Lydersen.

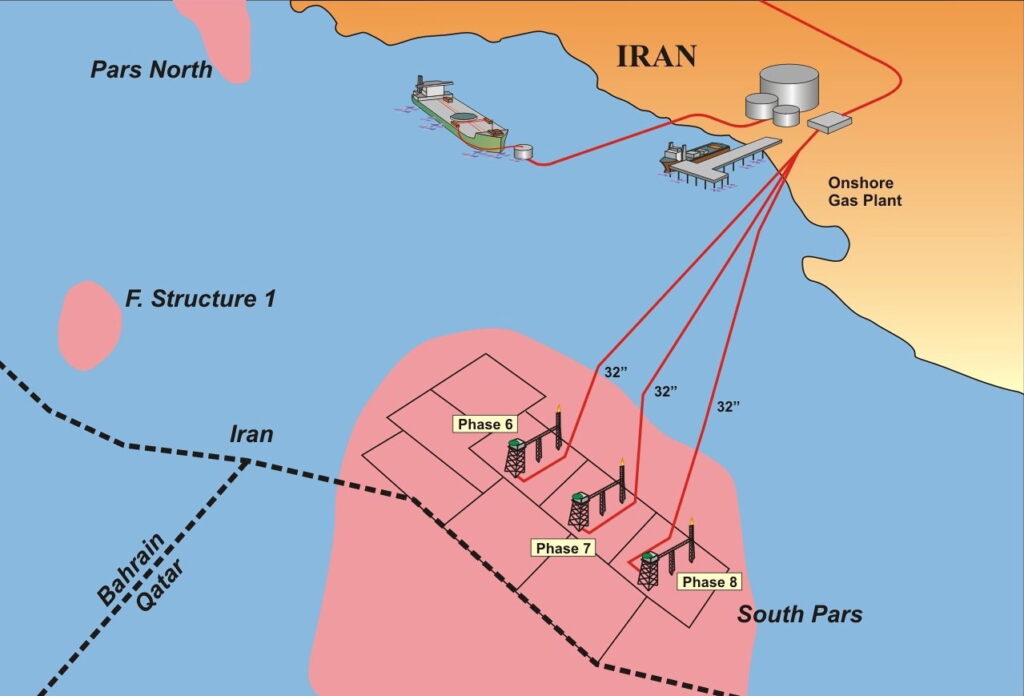

Statoil was particularly interested in South Pars, the world’s largest gas field, which lies in the Iranian sector of the Arabian Gulf. Given the company’s offshore expertise, this fitted well in its portfolio.

The breakthrough came in October 2002. Statoil secured a contract as operator for the sixth, seventh and eighth development stages of South Pars, which contains condensate as well as gas. Installing three production platforms and an equal number of pipelines to land demanded billions of kroner in investment and offered an exciting opportunity for the company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2003, Statoil: 20. The project was confined to actual development. Once that was completed, operation would be transferred to the NIOC. That resembled the occasion when Mobil had to relinquish operator responsibility for Statfjord to Statoil. A significant difference was that Mobil retained an equity interest in Statfjord. That was not the case in Iran, where foreign companies were merely refunded all their development expenses plus a specified mark-up. The NIOC owned the whole field and took all the profits from production. That was why Fjell commented: “Although the project in Iran is not a large one, it represents an important step in the development of our international business.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2002, Statoil: 3.

In order to secure access to future projects, Statoil pursued considerable activities aimed at business development in Iran. That included research on converting gas into liquid motor fuels, and studies of IOR opportunities on three oil fields in the southern Zagros region.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2003, Statoil: 20. Nothing ever came of that.

Corruption exposed

It was not long before skeletons were identified in the closet. Fjell was informed by the company’s internal audit function in April 2003 that a consultancy agreement entered into with a company called Horton Investments in London was irregular and should be cancelled. Mere months before securing the South Pars deal, Statoil had agreed to pay NOK 115 million over 11 years for advice on commercial operations in Iran. Two months after the contract was signed, Statoil remitted NOK 40 million to Horton Investments.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rugland, Ingvild and Aanestad, Morten, “Statoil-saken” article series, Dagens Næringsliv, 6 September-24 September 2003.

Following the alert from internal auditor Svein Andersen and security manager David Platts, the agreement was discussed in a meeting on 2 June between Fjell, Hubbard and executive vice president Inge K. Hansen. While the CEO did not like what he had heard, he did not consider the position so critical that the agreement had to be cancelled immediately.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 29 October 2003, https://www.dn.no/hubbard-alt-er-basert-pa-fakta/1-1-304149.

That proved a serious misjudgement. Journalists from Oslo business daily Dagens Næringsliv learnt of the payment. Its size and the length of the agreement aroused their curiosity, prompting them to ask who was behind these consultancy services and what they involved. Was this an “entry fee” paid to a country’s authorities for permission to do business? Such payments occurred in the international oil industry.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rugland, Ingvild and Aanestad, Morten, op.cit.

It was normal in Iran and other countries for oil companies to use consultants for advice on political issues and business conditions. The journalists established that Norsk Hydro did this, for instance, but in a way which was verifiable. When they contacted Statoil’s information department with questions about the consultancy agreement, nothing was known about it. They were referred to vice president Tor Ivar Pedersen, who was responsible for Statoil’s activities in Iran and who had signed the agreement with Horton Investments. However, he passed the buck further up to Hubbard, who told the journalists that the consultant was Abbas Yazdi and described him as a London-based lawyer. When Yazdi was visited at a modest address in the UK capital, however, he explained that he was an engineer and denied that any money passed to the authorities in Iran. At the same time, he revealed that Statoil’s actual consultant was Mehdi Hashemi Rafsanjani.

This confirmed the journalists’ suspicions that something was not right. Mehdi Hashemi was the son of former Iranian president Ali Akbar Rafsanjani, and a senior executive in an NIOC subsidiary.

Hubbard’s information, in other words, was inaccurate. The question then was what Fjell, his boss, knew. In an interview, the CEO reported that he knew about Mehdi Hashemi and was now aware of his family connections and position in the NIOC, but did not think they disqualified him. Nevertheless, he admitted that he feared the agreement represented corruption.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The story appeared in Dagens Næringsliv on 10 September, and proved a bombshell. Leif Terje Løddesøl, a businessman and lawyer who served as Statoil chair, demanded an investigation of the agreement. He wanted it considered by the board as quickly as possible.

It soon transpired that Løddesøl was not as ignorant as he had claimed in the press. The internal audit function had held meetings with him on the matter earlier, without provoking a reaction.

The press revelations had consequences. On 11 September 2003, the National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime in Norway (Økokrim) raided Statoil’s head office at Forus. The following day, it charged Statoil ASA with illegally influencing a foreign public servant – in other words, gross corruption. As a result, the board as the highest authority in the company had to accept responsibility for possible irregularities.

Consequences

Following the corruption charge, Fjell himself informed the press that Hubbard had resigned with immediate effect and the agreement with Horton had been cancelled. The latter thereby retained the USD 5.2 million (NOK 40 million) already disbursed, but received no further payments.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), 12 September 2003, «Statoil-sjef må gå».

The Statoil board met on 15 September at the company’s Oslo office. After sitting far into the night, it concluded that Fjell had shown poor judgement but had otherwise done such a good job for the company that he should remain in place.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.dn.no/olav-fjell-fikk-sparken-i-natt/1-1-286971.

Nevertheless, this did not happen.

Løddesøl himself was being economical with the truth when he told the press that he had informed other directors of the agreement before the story appeared. That was denied by these directors, who were dissatisfied with the management and the way the issue had been handled. Løddelsøl’s position hung by a thin thread.

Stein Bredal, group shop steward and a director, called for a new board meeting on 23 September. So did the three female directors – Kaci Kullmann Five, Eli Sætersmoen and Grace Reksten Skaugen. Løddesøl understood where matters were heading and resigned at around 23.00 on 22 September. The outcome of the board meeting on the next day was foreordained. Fjell also had to resign.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Borchgrevink, Aage Storm, 2019, Giganten: 292-298. Although he had preached ethics and sustainability, Statoil under his leadership had become involved in corrupt behaviour as part of the far-reaching culture of corruption which existed in the international oil industry.

Hansen became acting CEO on Tuesday 23 September, since the board took the view that he had not been involved with the agreement at all.

Sequel

Nevertheless, the affair had consequences for Hansen. Since he had attended a meeting on the issue with Hubbard and Fjell in June 2003 without reacting, he was not exactly guilt-free. He was therefore out of the running to become the new CEO.[REMOVE]Fotnote: DN, 29 October 2003, “Hubbard: Alt er basert på fakta”.

The corruption case ended up in both the Norwegian and the US courts. In Norway, the outcome was that Statoil and Hubbard were fined NOK 20 million and NOK 200 000 respectively by Økokrim. Fjell received no penalty. The company neither admitted nor denied any breach of the law or guilt in the matter. It nevertheless conceded that internal ethical guidelines had been broken.

After Statoil was partially privatised in 2001 and listed on the New York Stock Exchange, it had to abide by American law. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched its own investigation. Statoil had to pay a total of NOK 140 million, less the penalty imposed by Økokrim, in fines and forfeiture of profits after reaching a compromise with the SEC.[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://transparency.no/wp-content/uploads/dommssamling2017.pdf. With this settlement, the company regarded the case as closed.

Nor did Mehdi Hashemi Rafsanjani escape. He sought in 2012 to sue Fjell for defamation,[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.dn.no/statoil-stevnes-for-retten-i-iran/1-1-1898662. but was instead condemned in Iran to 15 years imprisonment in 2015 following several new corruption charges.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.dn.no/jus/naringsliv/15-ars-fengsel-for-tidligere-statoil-konsulent/1-1-5331569.

Withdrawal from Iran

In 2006, the UN imposed sanctions on Iran to prevent the country from developing nuclear weapons. Norway was bound to comply with this action, but it did not affect oil operations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2007-02-09-149. In 2012, the USA and the EU intensified sanctions for the petroleum sector, and it gradually became more difficult to operate as a western oil company in Iran.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.fn.no/Konflikter/Asia/iran.

Statoil nevertheless remained there for a while to complete its gas project. In July 2003, it closed its last office in Iran after having invested more than NOK 4 billion there. The development job on South Pars was completed.

As mentioned above, the form of agreement for foreign enterprises investing in Iran was that the oil company, for example, invested in and developed a field, and ownership was delivered to the NIOC when the facilities were ready to produce. The international participant then had its costs met and received either a specified return or a share of the profit. That meant the oil companies could lose out on big earnings if the field developed better than expected or petroleum prices rose considerably.

Statoil therefore withdrew after having its outstanding claims met by the NIOC.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), 12 October 2013. Some of the UN sanctions were removed in 2016. It is not clear whether the last word has been said on Equinor’s involvement in Iran. That will depend on the company’s future strategy, the host country’s treatment of foreign oil enterprises, and its relations with other countries – particularly the USA and the EU.

arrow_backGassco – background, creation and functionInge K. Hansen – from listing to merger soundingsarrow_forward