Helge Lund – commitment to growth

Lund’s plan was to shift Statoil from being a Norwegian oil company with foreign activities to an international player which looked more like its major international competitors.

This expansion was to be largely achieved upstream – exploring for and producing oil and gas. That meant a definitive farewell to the project pursued by Arve Johnsen, Statoil’s first CEO, of creating a vertically integrated company involved in everything from seismic surveying to operating service stations. High petroleum prices encouraged a growth strategy with the emphasis of a global search for large new reserves. These would replace what was perceived to be an inevitable downward trend on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).

Freer hands

That strategy was influenced by Statoil’s status as a partly-privatised company with greater freedom to pursue commercially driven growth. The foreign commitment benefitted throughout almost the whole of Lund’s time in office form the good money made by Statoil through a high level of production on a mature NCS.

His early days at the company were characterised by efforts to adapt the organisation to the growth strategy. One example was dropping the traditional use of budgets in order to improve opportunities for relevant business areas (like international exploration and production, and development and production Norway) to respond to opportunities which offered themselves.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See Boon, Marten, 2022, En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001. Universitetsforlaget: 125.

Another important factor fell into place when Statoil merged with Norsk Hydro’s oil and energy division in 2006-07, after detailed groundwork to secure the necessary political backing. Many observers regarded the merger as an important element on the way to becoming a company with muscle which could be a serious internationally competitor.

Brazil and the USA

The growth strategy had several facets while Lund was in charge. First, it involved continuing to collaborate with national oil companies (NOCs) in other countries – the “NOC-NOC” strategy. An important example here was the move into Brazil, where Statoil secured licences and gradually built itself up as an operator.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The significance of the Brazilian commitment was also underlined when Norway’s Crown Prince Haakon performed the official inauguration of Brazil’s Peregrino field in 2011. See Lien, Solveig U., ”Åpnet Peregrino-feltet”, Stavanger Aftenblad, 25 May 2011: 21.

Replacing old reserves with new was one of Statoil’s top priorities under Lund. To achieve that, it concentrated to a great extent on inorganic growth by such means as the acquisition of established oil companies. Although this was expensive, it meant that Statoil got going with oil and gas production relatively quickly – advantageous when prices were high.

The management believed that much of the potential for such inorganic growth lay in the USA. High oil prices made it profitable to produce shale oil and gas, which are found in large quantities in this part of the world. Pursuing resources on land marked a new departure for a company whose expertise and organisational profile had always been primarily focused on offshore installations, and presented several challenges.

With commitments around the world – in Brazil and the USA, for example – ambitious goals were set for Statoil’s production. The 2012 annual report announced an aim to produce 2.5 million barrels per day by 2020.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2012, Statoil: 1. (References to annual reports in this text refer to the Norwegian edition of the reports.)

Restructuring

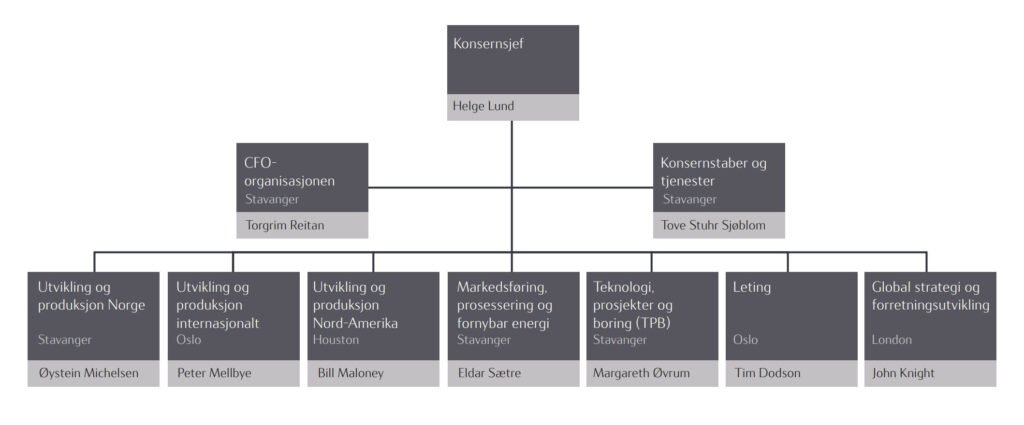

This heavy concentration abroad and ambitious production goals demonstrated the company’s growth ambitions and that it had truly become a substantial international petroleum company. By 2011, the time had come for this also to be clearly reflected in the company’s formal organisational structure.[REMOVE]Fotnote: This attracted much media attention. See, for example: “Store endringer i Statoil-ledelsen”, Aftenposten https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/JJReb/store-endringer-i-statoil-ledelsen, accessed 14 December 2021.

The global commitment was primarily manifested in a reshaped group structure with new business areas. These were exploration, global strategy and business development, and development and production North America.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2011, Statoil: 4; Boon, Marten, op.cit: 228. Moreover, traditional views of where Statoil’s business areas should have their head offices were challenged. That applied both to global strategy and business development and to development and production North America, which were based in London and Houston respectively.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

NCS

The NCS was Statoil’s home turf and “cash machine” – particularly in times when oil prices were high. A big commitment was also made there, with almost NOK 400 billion invested in 2004-14. On average, however, exploration and development costs off Norway were lower than abroad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, op.cit: 266-267. Statoil’s close relationship with the government and the supplier industry were among the many factors contributing to this.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 267.

Put simply, the main job on the NCS was to recover as much as possible of the resources in fields already on stream while making smaller new discoveries. The day of the big finds was thought to be done – with one big exception. Discovering Johan Sverdrup in 2010 showed that the NCS still contained big reserves.

Price slump

Involving more or less the entire industry, the big hunt for reserves had driven costs sky-high. With production therefore up – and higher than the market could absorb – oil and gas prices slumped.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 290.

This downturn began in 2014 and had a big impact on Statoil’s profitability, including the investments it had made in the USA. However, the company had initiated cost-saving measures before prices began to fall.

When Lund accepted the job of heading the UK’s BG Group in 2014 and resigned as CEO of Statoil, he left a company with big engagements abroad.

During the final part of his time at the helm and in the transition to his successor, Eldar Sætre, adjusting operations to a lower level of oil prices became a key task.

arrow_backHelge Lund – background and appointmentBlowout on Snorre A – enormous potential for major accidentarrow_forward