Oil and the environment in Australia

Interests were acquired in four BP-operated offshore licences in 2012. They lay in the Great Australian Bight to the south of the continent – an area known for its rich fishing. Statoil opted to establish an office in Adelaide, capital of South Australia and geographically close to the new exploration area. This was later transferred to Perth in Western Australia. The company also secured an operatorship on land in the Northern Territory’s South Georgina Basin.

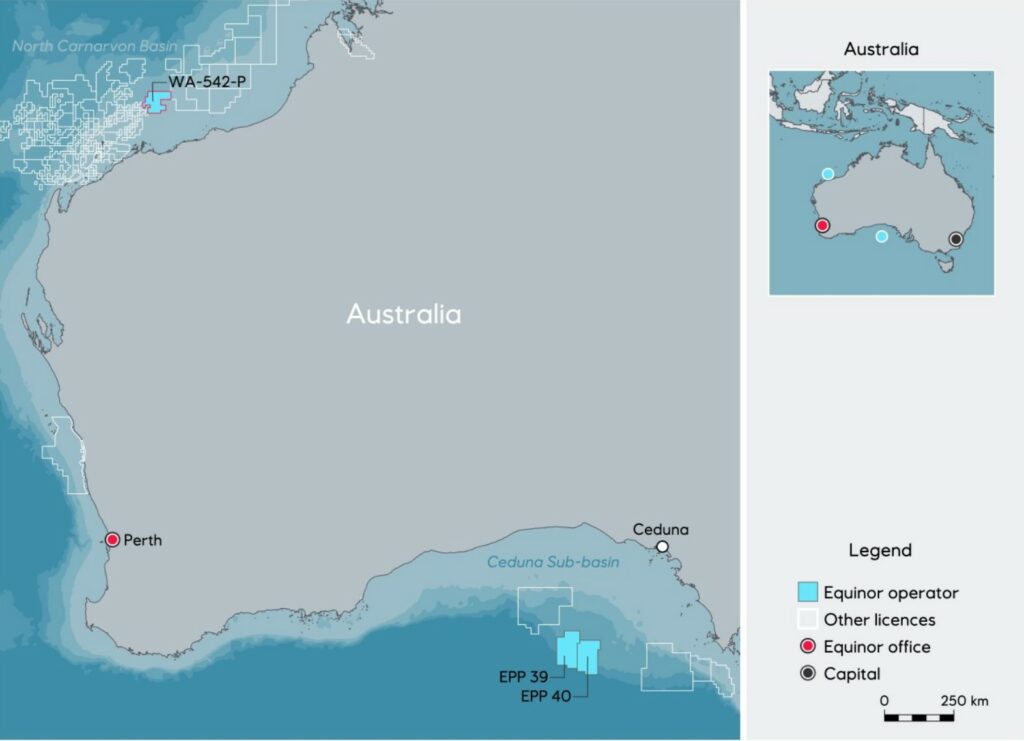

Exploring in the north-west

The next step was the acquisition of an exploration licence, as sole licensee, in the Northern Carnarvon Basin off Western Australia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: From the National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (Nopta), through the 2013 offshore petroleum exploration acreage release. Large quantities of gas had been proven in other parts of this basin, and several fields were on stream.

Covering more than 13 000 square kilometres, the acreage was 300 kilometres from land and had water depths of 1 500-2 000 metres. Statoil was committed to acquiring seismic data over a three-year period.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Offshore Energy, 24 October 2014, “Statoil expands off Australia”.

The 2018 Dorado oil discovery in an area closer to land increased optimism.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/dorado-oil-and-gas-discovery/. Equinor, as the company was now called, decided to apply for more acreage closer to land. In September 2019, it succeeded in securing the operatorship of yet another exploration licence running for six years. This block covered 4 815 square kilometres about 100 kilometres off the coast, with water depths varying between 80 and 350 metres. The work programme covered geological and geophysical studies and acquiring three-dimensional seismic data.

Paul McCafferty, Equinor’s senior vice president for international offshore exploration, commented that he was pleased the company had secured a licence in an area where oil was already proven.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor press release, 10 October 2019, “New exploration permit offshore Australia’s northwest shelf”.

Protests in South Australia

The four areas in the Ceduna Basin off South Australia where Statoil initially secured exploration rights in partnership with BP proved problematic.

Operator BP refused in 2016 to conduct drilling in the area because it was too uncertain and expensive.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/news-and-insights/press-releases/bp-decides-not-to-proceed-with-great-australian-bight-exploration.html. This was during the 2041-18 oil crisis, when crude prices were very low. Statoil took an understanding view of this. The following year, a swap deal gave it the operatorship of two of the four, with a 100 per cent holding. BP took full control of the other two licences.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor press release, 10 October 2017, “Great Australian Bight”.

The 12 000 square kilometres where Statoil became the operator were known for their rich fish and animal life. It was the haunt of 36 species of whales and dolphins, the world’s most important southerly breeding ground for whales, and home to the rare Australian sea lion. These factors made oil exploration there controversial.

Although the Australian authorities had not put any protection in place for the Bight, oil companies given exploration licences had to produce an environmental plan for their operations. That was not enough for the green activists.

Chevron also withdrew from further drilling in the autumn of 2017 for the same reason given by BP – it was not financially viable. Statoil/Equinor took a rather more positive view of the position and planned to drill the Stromlo-1 well in the Bight during 2019. It drew up an environmental plan which showed that the work could be done in a secure way by building on its long experience. This plan was approved by Australia’s National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (Nopsema), and Equinor press spokesperson Bård Glad Pedersen stated that the company was optimistic about opportunities for discoveries in the area. Exploration would be implemented securely and in accordance with Australia’s strict environmental requirements related both to fishing and tourism.

Opponents of oil operations in the Bight were not convinced. They did a lot to attract attention to their cause. Peter Clements, the mayor of Kangaroo Island close to the drilling locations, attended Statoil/Equinor’s annual general meeting in both 2016 and 2018 to express opposition to the work. That included submitting a letter from indigenous population groups to Statoil.

Luke Chamberlain from Australia’s Wilderness Society was also present at these AGMs. He maintained that it was important to protect the fishing and tourism industries, which created almost NOK 10 billion in value every year, and that Equinor had to live up to its new name and its commitment to a future with lower carbon emissions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 15 May 2018, “Statoil møter sterke protester i Australias Lofoten”.

CEO Eldar Sætre took the view that the planned drilling was entirely acceptable in environmental terms, despite the strong opposition from the green movement. “It’s a long way from land. These are things we’ve done in Norway for many years and are very comfortable with,” he said. Sætre emphasised that the Australian petroleum directorate was very competent and set strict standards, and that exploration drilling had broad political support at local, state and national level in Australia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

A number of protests were staged against Equinor’s plans in the Bight, and received broad media coverage. In January 2020, the Wilderness Society took the Nopsema decision to court on the grounds that Equinor had failed to consult the local authorities and indigenous population during the process.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK/NTB, 25 February 2020, “Equinor dropper omstridt oljeleting i Australbukta”.

Retreat

The matter took a new turn in 2020, when Equinor decided to shelve its drilling plans in the Bight. Local surfers who had arranged a series of “paddle-out” protests could now celebrate. Like BP and Chevron before it, the company said this decision was taken because the project was not commercially competitive with other exploration targets in its portfolio.

Although Equinor did not pursue planned operations in the Bight and withdrew from the area, the company insisted that this did not affect its other activities in Australia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor press release, 25 February 2020, “Equinor to discontinue exploration drilling plan in the Great Australian Bight”. That assertion turned out to be short-lived. As early as 2021, Equinor was moving out of Australia at full speed and now no longer has any activity there.

arrow_backIT services from IndiaFrom Statoil to Circle Karrow_forward