Long wooing for access to Russia

Both during and after the Cold War, relations between Norway and Russia had been relatively good. The exception was the “grey zone” boundary line in the Barents Sea, which had been discussed numerous times by ministers and civil servants from both sides. This issue not only involved fish resources, but also the fact that oil and gas deposits had been proven in both sectors of this sea. The question was whether the two countries would benefit from collaborating over the development of petroleum resources.

Bilateral deal

The Norwegian government was positive to strengthening collaboration in the far north. During a visit to Norway in 2002, Putin signed a wide-ranging agreement with Norwegian premier Kjell Magne Bondevik on bilateral oil and gas cooperation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nrk.no/norge/enighet-om-samarbeid-1.507740 https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-30-2004-2005-/id407537/sec3. Norway hoped that working together in this way could increase the profitability and viability of recovering its own resources in the Barents Sea, where the Snøhvit gas field was under development.

Statoil had previous experience with Russia, having been briefly involved there during the 1990s in partnership with BP. An office was opened in Moscow, but the bureaucratic way the Russian oil industry was run made it difficult to do business and the whole effort was called off.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nb.no/items/78b6ff1d107cd9bd1a74c7e80e435942?page=19. Nevertheless, Statoil entered into a strategic deal on its own account with Russia’s Gazprom in 1996 to develop a possible oil discovery in the Pechora area of Siberia, where finds had been made in three blocks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board minutes, Statoil, item 7/96-5, “Redegjørelse for virksomheten”. Hydro joined this collaboration in 1998.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board minutes, Statoil, item 5/98-2, “Konsernsjefen orienterer”. Given low oil prices around 2000 and its cost overruns on Åsgard, Statoil decided to cut back in Russia and elsewhere and cancelled the Gazprom agreement in 2001.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Njål Gjedrem in an e-mail to Kristin Øye Gjerde, 6 February 2022.

But the oil world changes fast. The following year, CEO Olav Fjell opted to allocate additional staff and resources to the company’s office in Moscow. In September 2003, Statoil approached Gazprom with a request to participate in the new consortium which the Russian company was planning for the Shtokman discovery in the Barents Sea.

Helge Lund maintained this commitment on becoming CEO in 2004. He had met Putin during the president’s state visit in 2002, and become convinced that Norwegian companies had good opportunities to succeed in Russia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: This article is partly based on Boon, Marten: En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001. Universitetsforlaget 2022: 289- 298. The annual report for 2004 stated that Statoil was making a commitment to Russia as a new core area. It and the Barents Sea were established as new business units and given extra expertise and resources.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2004. The company was willing to go to considerable lengths to participate in a possible Shtokman development.

Three times Troll

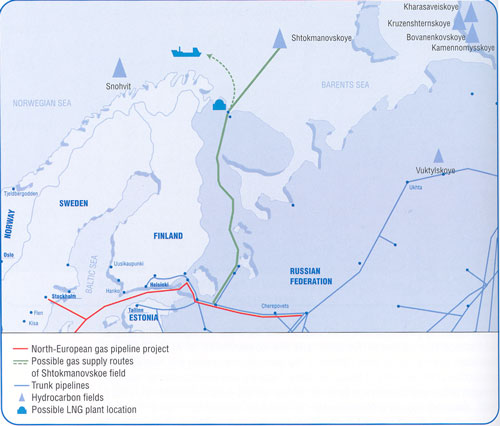

Proven west of Novaya Zemlya as early as 1988, this discovery was ranked as one of the world’s largest known offshore natural gas deposits. It was estimated to contain 3.8 billion standard cubic metres of gas, or two-three times more than Troll – Norway’s largest gas field. Its name comes from Vladimir Sjtokman (Stockman), a Russian oceanographer of German extraction.

The development licence was held jointly by Gazprom and Rosneft, both state-owned and without had experience of offshore operations. Bringing Shtokman on stream would be complicated by intense cold, ice and currents. The field also lies in 350 metres of water, almost 600 kilometres from land.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stockman. Its distance from major gas markets added to the development challenge. To secure sufficient expertise to tackle these issues, the Russian companies collaborated with several foreign partners in the 1990s – including Hydro. This group failed initially to find a financially viable solution, and the project was shelved in 2002.

Door opener

In the same year, however, and after many attempts, Statoil had secured approval to develop the Snøhvit gas field in the southern Barents Sea. Production from subsea wells was to be piped roughly 140 kilometres to a processing plant on the island of Melkøya off Hammerfest. After separation, the gas would be dewatered and cooled down until it became liquefied natural gas (LNG) and could be shipped worldwide in specially designed carriers with spherical tanks. Export markets included the USA, where rising demand and declining domestic production were driving up prices.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Nergaard, Arnfinn, 2019, Getting Down to It. 50 Years of Subsea Success in Norway: 196-200. As part of the Snøhvit project, Statoil had a contract to use the Cove Point LNG import terminal on the American east coast. With that access to the US market, the company could point to a possible profitable solution for Shtokman. This inspired Gazprom in early 2013 to start reassessing a development of the field.

Hydro, which had contributed to the search for Shtokman solutions in the 1990s, was not especially pleased to see rival Statoil become involved in late 2003.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten: En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001. Universitetsforlaget 2022: 289- 298. This was particularly irritating because Hydro was also in the process of selling its 10 per cent interest in Snøhvit – the project which revived Gazprom’s interest in Shtokman.

In September 2004, Statoil signed a letter of intent with Gazprom and Rosneft covering possible reciprocal stakes in Shtokman and Snøhvit. This also offered Statoil an opportunity to exploit Cove Point capacity to sell Russian gas to the USA.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2004.

Hydro secured a similar deal not long afterwards. Gazprom’s desire to collaborate with the two companies indicates how similar their expertise was. Although Hydro was no longer involved in the LNG project, both it and Statoil had much experience with subsea systems and multiphase flow pipeline transport. Gazprom also invited other companies, including Shell, Total, Chevron and ConocoPhillips, to submit development proposals.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, op.cit.

Rivals in Russia

Securing involvement in a Shtokman development would not only open big opportunities for Statoil and Hydro, but also be of great significance to the Norwegian government. This promised bilateral collaboration with the big neighbour to the east, development of Arctic oil and gas, and international expansion for Norway’s oil and gas companies. So it is hardly surprising that the Shtokman issue attracted far greater public attention than earlier international commitments by the two companies. But it quickly became clear that, despite both being owned by the Norwegian state, they were rivals internationally. The question then was which company the government should support, and what significance it would have if the Russians chose to collaborate with one rather than the other.

Russian procrastination

Gazprom spent a long time assessing offers from all the companies, and issued ambiguous signals about which development solution it preferred. During a state visit by Bondevik to Russia in June 2005, further efforts were made to facilitate a bilateral oil and gas collaboration between the two nations. A collaboration agreement on exploration in the Arctic – excluding Shtokman – was reached between Gazprom, Rosneft, Hydro and Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.aftenposten.no/verden/i/bgonq/norsk-russisk-avtale-om-barentshavet.

Proposals for a possible development of Shtokman were submitted by Statoil in late April 2005.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2005. Nevertheless, Gazprom asked all its partners to provide new plans during January 2006.

The Russian company now had two possible solutions for selling LNG. Opting for the Snøhvit model meant it would be dependent on the foreign partners delivering technology, expertise and market access to the USA. Its other option, which had been pursued since the 1990s, was to lay a gas pipeline – now known as Nord Stream – through the Baltic to Germany. That way, Gazprom could avoid the former eastern bloc countries which were increasingly influenced by Nato and the EU. Although the company showed enduring interest in the LNG concept, it never entirely dropped the pipeline solution.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, op.cit.

Collaboration not competition

The constant delays created considerable frustration at Statoil and Hydro. Both Lund and Eivind Reiten, his opposite number at Hydro, increasingly feared that Gazprom might opt for one rather than both of the companies.

From their different perspective, the two CEOs reflected on what benefits and drawbacks might be obtained in this area by a merger between their two companies. They initiated talks on the issue in deepest secrecy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. Shtokman was such a big project that it could give a very negative impression if only one of the two was selected.

The companies requested Gazprom formally in January 2006 to be treated as a joint bidder for Shtokman. This initiative was supported by the Labour government under Jens Stoltenberg, who had replaced Bondevik in October 2005.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Stoltenberg was convinced that a closer collaboration between Hydro and Statoil would improve their chances of success. But even this move failed. In October 2006, Gazprom dropped a bombshell by announcing that it no longer wished to cooperate with foreign partners – including the two Norwegian suitors. Statoil nevertheless made it clear that the company had a long-term intention of pursuing commercial opportunities in Russia with the aid of its strong technological expertise on and experience of big, complex developments.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, Statoil, 2006.

Russia and the Barents region

The drawbacks of being competitors internationally helped to prepare the ground for a merger between Statoil and Hydro’s oil and energy division, which occurred in October 2007. During that year, Gazprom had changed its mind yet again, and decided that foreign companies could participate in the first phase of a Shtokman development. StatoilHydro, as the merged enterprise was called in 2007-09, signed a frame agreement with the Russian company on 25 October 2007 concerning this involvement.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, StatoilHydro, 2007.

Shtokman Development AG (SDAG) was established in February 2008 to develop and operate the first phase. This company was owned 51 per cent by Gazprom, 25 per cent by Total and 24 per cent by StatoilHydro. The three partners supplied personnel, and the joint venture set up shop in both Moscow and Paris to plan the offshore part and the LNG terminal respectively. SDAG opted to pursue a floater solution based on a production ship rather than a platform. Gas would be piped for 600 kilometres to a liquefaction plant in the out-of-the-way town of Teriberka, 120 kilometres east of Murmansk. The bulk of the gas would nevertheless be sent to Europe via the planned pipeline.

Project planning and execution plans were much more bureaucratic than Statoil’s personnel were accustomed to. A review by the company showed that it would take several years longer to get the facility operational than the project’s official plans assumed. Before the shareholder agreement expired on 30 June 2012, Statoil concluded that the project was not feasible. It therefore pulled out, wrote off its investment and transferred the shares to Gazprom. Total also withdrew in 2015, and no progress has been made since.

Oil industry veteran Helge Hatlestad, who followed the whole planning process, maintains that no other project in Statoil or Hydro received so much management attention and business development funding without any return whatsoever.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, 2021, Femti år med oljeproduksjon. Min historie, privately published: 254.

New alliances

But this did mean a full stop. Statoil continued to maintain a presence in Russia. After the Barents Sea boundary between the two countries was finally clarified in 2010, the company entered into a strategic collaboration with Rosneft. This agreement covered several joint projects, including the North Komsomolskoye test for bringing viscous crude ashore in western Siberia. Another was a three-year pilot for developing the Domanik carbonate formation in the Samara region, while a third covered offshore exploration.

From 2020, Equinor also had a 49 per cent holding in the AngagaOil LLC company, which holds 12 exploration and production licences on land in eastern Siberia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor website, accessed 11 August 2021. The company was also a partner in the Kharyaga oil field, proven as long ago as 1970.

War brings abrupt halt

When Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the country was hit by extensive western sanctions. Equinor’s board decided a few days later to halt new Russian investment. It also launched the process of withdrawing from its existing joint ventures there. At that time, the carrying amount of the company’s fixed assets in Russia was USD 1.2 billion.

“We are deeply disturbed by the invasion of Ukraine,” said CEO Anders Opedal. “It represents a terrible setback for the world, and our thoughts go to all those suffering from the military assault.” The company was concerned for its employees, and wanted to extend humanitarian aid to those affected by the war.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/news/archive/20220227-equinor-start-exiting-joint-ventures-russia

arrow_backKristin – high pressure and temperatureUnrewarding power-from-gas effortsarrow_forward