Wooing the state oil companies

Norwegian oil policy attracted interest in other countries as early as the 1970s. Foreign delegations frequently visited Statoil’s head office in Stavanger to be introduced to the “Norwegian way” of organising the petroleum industry. Other nations wanted to learn from the company’s success. Mutual contacts and exchanges of experience were also important for Statoil as it sought to move out into the world.

Strategy in the melting pot

The company’s first foreign subsidiary on the upstream side – in other words, exploration and production – was established in the Netherlands in 1983. Similar foundations followed in Denmark, the UK and China, but with a relatively limited engagement during the early years.

After Harald Norvik took over as CEO from Arve Johnsen in 1988, an internal strategy project was launched in 1989 with consultant McKinsey. Its aim was to assess Statoil’s international commitment and develop a new approach, and the conclusion was clear – efforts that far had been irresolute and fortuitous.

The project recommended that Statoil, through acquisitions or alliances, had to secure control of oil reserves where production costs per unit produced were lower than on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). That would increase profits. At the same time, the company could apply and further develop its expertise by working in these attractive areas. The goal was for Statoil to produce a third of its petroleum abroad by 2000.

According to the report, the company’s Norwegian background could offer benefits. It might, for example, be easier to secure access in nations which had received development assistance from Norway. Alternatively, some countries might prefer to collaborate with a company from Norway, which had no history as a colonial power and did not represent a threatening great power in other ways. Furthermore, Statoil’s state-owned status could be advantageous in others when compared with “capitalistic companies”. Countries such as Albania, Vietnam, Angola and Mexico were cited as examples.

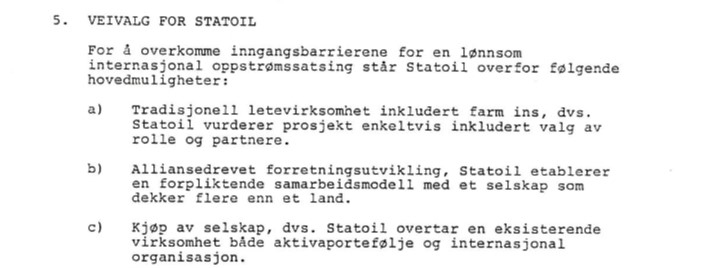

Three primary strategies were possible: 1) go it alone, 2) acquire other companies or 3) enter into partnerships/strategic alliances.[REMOVE]Fotnote: McKinsey & Company, Inc, Developing a successful international E&P business, Statoil A/S, first progress review, 14 November 1989. All these approaches were given serious consideration by Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/17707/WP_nr16_Ryggvik_BP.pdf?sequence=1.

The first strategy of going it alone by bidding for licences and building up a business from scratch through exploration and then development was always a possibility. Nor was the second option of acquiring other oil companies excluded. But entering into strategic alliances was the preferred choice. That would provide international experience.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy, no 3, 1990: 17.

Door-opener

A strategic alliance forged with BP in 1990 made its mark on Statoil’s new commitment abroad throughout the 1990s.

Although this partnership ranks as the best-known of the strategies pursued by Statoil during Norvik’s time at the helm, it was not the only one. The company also made contact with several other national oil companies (NOCs) with a view to possible collaboration – known as the “NOC-NOC” strategy.

This involved sending out Statoil personnel to make contact with other state-owned enterprises. These were usually in energy-rich developing countries where the company, as a successful NOC from a peaceful little nation, could offer technical expertise in deep water.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ole Johan Lydersen, Equinor’s 50-anniversary Facebook page, 3 November 2019. Statoil achieved success in some of these countries, but in many cases the conclusion was that the risk of involvement was too high given its limited international experience. A number of these offensives were mounted ahead of the Statoil/BP alliance and a less well-known, but deserve a place in the company’s history.

“Some of the countries visited were among the most socialist, communistic and closed countries in the world,” recalls Ole Johan Lydersen, who was head of international business development for Statoil and one of the “knockers on doors”. That applied to Cuba, for example, where Statoil was one of the first oil companies to make an attempt in 1989-90. “We knocked on the door and said ‘We’re Statoil, the Norwegian state oil company, and might like to cooperate’. Then we asked if there were any opportunities for collaboration projects.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Albania was also extremely closed. Its leader since the Second World War had been the communist Enver Hoxha. During his rule, people could be executed for travelling abroad. Six years after Hoxha’s death in 1985, Statoil was able to visit Albania’s capital Tirana and negotiate for offshore exploration licences. That made it one of the first western companies to visit the country – if not the first.

A visit was also paid to the Bulgarian state oil company in Sofia during 1990, where opportunities for conducting oil production in the Black Sea were considered – without success.

Far more important and complicated were efforts to become established in the Soviet Union. Around 1990, Statoil was in talks with deputy minister Boris Nikitin at the Ministry of Oil Industry and ex-minister Nikolai Baybakov, who had held very key positions in the economic and energy sectors after the Second World War.

The position changed with the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991. Since then, Statoil has been involved to varying degrees in Russian exploration and production as well as operating service stations. The last of the latter, in Murmansk, was sold in 2012, while the company withdrew on the production side when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.

NOC-NOC collaboration during the alliance

Statoil’s desire for an international involvement fitted well with BP’s search for a partner who could strengthen it financially after a difficult period in the late 1980s. Their alliance created a platform for further growth internationally.

The two companies resolved to concentrate on three areas. These were the former Soviet Union – Russia as well as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan around the Caspian – Angola and Nigeria in west Africa, and Vietnam and China.

In the late 1980s, one of China’s state oil companies opened big offshore areas to foreign companies. Statoil, which had so far been an adviser to the Chinese without getting very much back for it, had sought to secure a foothold with the state oil companies.

But it was not until the BP alliance that the company became involved in China on the exploration side, with its partner as operator. When BP withdrew in 1994, Statoil continued on its own account and became operator of the Lufeng field in the South China Sea up to 2005.

As part of the 1990 agreement, Statoil farmed into BP’s offshore licences in Vietnam. State oil company PetroVietnam was also involved in these, with BP as operator. That gave Statoil an interest in prospects where gas was later discovered. After its alliance with BP ended, however, the company resolved to divest its share in the Nam Con Son project and wind up its Vietnamese activities.

Off on its own

The Statoil/BP alliance was terminated at the beginning of 1999 after the latter had merged with Amoco. Activities continued in most of the countries where the company had got started, with Azerbaijan and Angola as the most profitable.

Olav Fjell, who succeeded Harald Norvik as CEO in 1999, wanted to strengthen the foreign commitment. The following year, he appointed ex-BP executive Richard Hubbard to lead this work. That included putting out feelers over an involvement in Iran.

Initial engagement with the Middle Eastern country appeared promising. Statoil’s envoys were well received, with meetings in Teheran and Ahwaz as well as a cultural excursion to Esfahan. Iranian oil minister Bijan Zanganeh was regarded as a good friend of Statoil. The state-owned National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) entered into a technology collaboration with Statoil to improve oil recovery from the Zagros field.

Statoil was particularly interested in the South Pars field in the Persian Gulf. Following several rounds of negotiations, the breakthrough came in 2002 and the company secured its first licence. However, it eventually emerged that a consultancy agreement entered into ahead of the award was to be regarded as corruption. This Horton scandal meant that both Fjell and Hubbard had to resign, and only the one agreement was reached before Statoil withdrew from the country.

NOC-NOC loses significance

Several examples can be cited of successful collaboration with state oil companies. One of the most prominent is in Brazil, where Petrobras long held a monopoly of national oil production. When that was terminated in 1997, the government wanted to attract foreign expertise to help develop deepwater fields. That presented a good opportunity for Statoil, which had the advantage that the subsea technology environments in Norway and Brazil were already fairly familiar with each other. Statoil secured its first offshore licence interests in 2001, and later obtained operatorships. Brazil has thereby eventually become one of the company’s most important priority areas for petroleum internationally.

The NOC-NOC strategy continued after Helge Lund became CEO in 2004, with John Knight as head of the international business area, but it no longer dominated. Greater attention was paid to acquiring other oil companies, in line with another of the proposals in the 1989 analysis mentioned above. The strategy for foreign involvement became dominated by a more market-oriented mindset. The merged StatoilHydro company opted from then on to make a massive commitment to industrial countries without state oil companies, such as the USA and Canada.

arrow_backWhen an iceberg grew into a mongTen years in Thailandarrow_forward