Harald Norvik – a purposeful leader

Norvik was born in 1946 at Vadsø in the far north of Norway, but his family moved when he was four to the Gjøvik area north of Oslo. After graduating from Fredrikstad commercial college, he took an MSc in business economics at the Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen in 1971.

Like his predecessor at Statoil, Norvik had close ties to the Labour Party. He became secretary to the party’s group in the Storting (parliament) responsible for industrial and financial matters in 1973.

He went on to serve as personal secretary to Labour prime minister Odvar Nordli in 1976-78, and was then appointed state secretary (junior minister) at the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 1979-81.

After the Labour government lost office in 1981, Norvik secured a job with the Aker group – whose activities included supplying to the oil industry. He occupied several management posts there. Before taking over as Statoil CEO, he was CEO of Astrup Høyer and a divisional vice president at Aker.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk biografisk leksikon, https://nbl.snl.no/Harald_Norvik

Norvik joined Statoil at a time when confidence in the company had been seriously weakened after a period of political attack. It had been accused for a number of years of acting as a state within the state. Big cost overruns incurred in an expansion project for the Mongstad refinery north of Bergen had been the last straw, particularly for the non-socialists, and Johnsen had to go.

Little blue book

Norvik had his doubts when he agreed to take over the top job. He was a different type of leader from Johnsen, with a more indirect style. But he made himself clear and aroused trust.

In his view, an important task was developing the organisation. He was always careful to keep people informed and to involve the unions. Norvik drew 60 senior Statoil executives and union leaders into developing a management strategy during the autumn of 1988. That collective effort yielded a 50-page document on goals, values and management. Known in Statoil as “Harald’s Little Blue Book”, this was intended to lay the basis for the company’s corporate culture. All employees, and managers in particular, had to internalise it.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Finn Harald Sandberg, 21 September 2020.

Norvik felt that management was more than running big developments, writing memos and chairing meetings. He believed it was people who created results. In his view, the managerial role conferred responsibility for other people’s development and growth, and was something which required a respectful attitude. Good management would yield a better organisation, which would in turn strengthen competitiveness and improve profits. And a good organisation had to be regularly cultivated.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 1, 1989. https://www.nb.no/items/fc7a042be5e22fe244b15044a16a48c7?page=1&searchText=

Depoliticising Statoil

While Norvik had been part of the innermost circle in the Labour Party’s top leadership during the 1970s, he was a businessman in the 1980s. This change meant that, when he took over at Statoil, his goal was to lead the company towards a less political position and more purposeful commercial operations. In a symbolic gesture, he resigned from the Labour party and maintained an open line to all Norway’s political groups. Statoil was no longer to be seen as social democracy’s company or instrument.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storsletten, Aslak Versto, 2018, Prosessen bak delprivatiseringen av Statoil i 2001 – fra selskap til vedtak, master’s thesis in history, University of Oslo: 26-27.

While Johnsen had been concerned with nation-building, Norvik believed it was no longer a key Statoil objective to help develop a Norwegian offshore supplier industry through contract awards. Giving domestic companies preferential treatment became in any event far more difficult after Norway joined the European Economic Area in 1994.

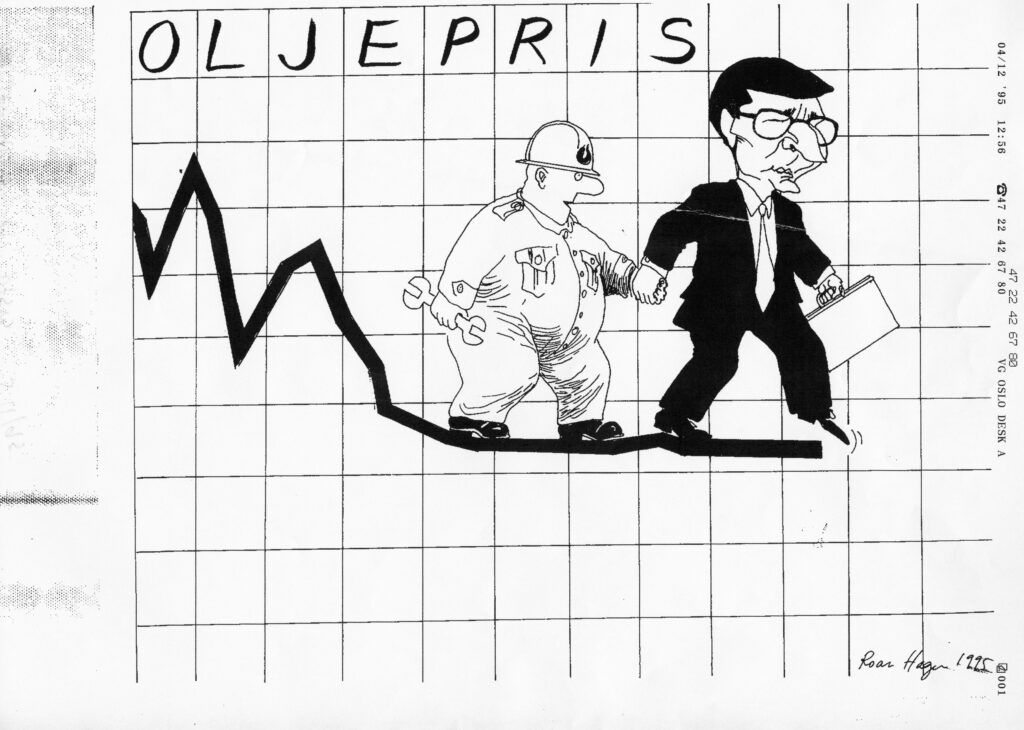

Securing the finances

At a time of low oil prices, strengthening the company’s finances was important. When Norvik took over, he worried that its equity was low and wanted to do something about this. His aim was to increase it from 12 per cent on arrival to 20 per cent by 1991 and 25 per cent in 1995.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 1, 1989. https://www.nb.no/items/fc7a042be5e22fe244b15044a16a48c7?page=1&searchText=. He later persuaded the government to refrain from taking the maximum possible dividend until the equity ratio was 35 per cent. In his view, this agreement represented a declaration of confidence.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storsletten, Aslak Versto, op.cit: 26-27.

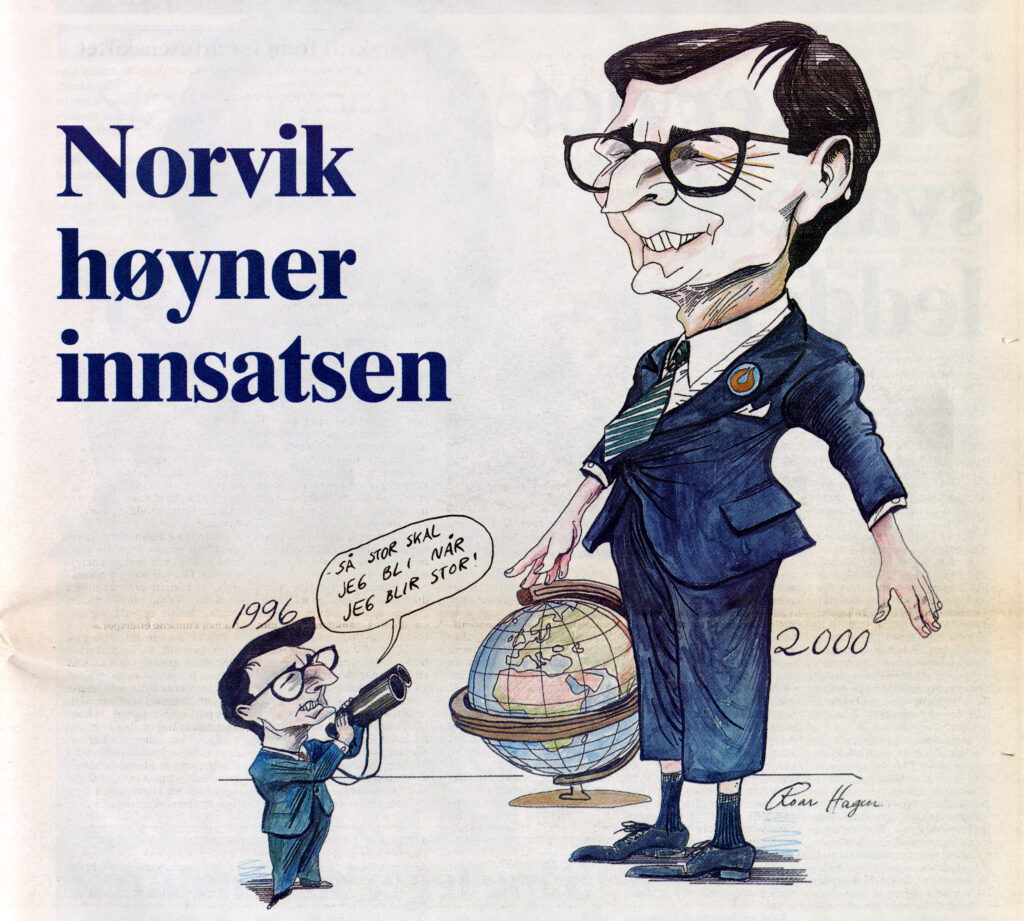

International commitment

At the Stavanger oil show in 1990, Norvik announced that Statoil had entered into an alliance with BP. The two companies would pursue joint exploration for and production of oil in a number of newly opened petroleum provinces around world, including Azerbaijan, Angola, Nigeria and Vietnam.

Norvik considered it existentially important for Statoil to be able to continue expanding. Without a growth potential, he believed the company would find it hard to maintain its whole organisation. At a meeting of the Polytechnic Society, Norvik gave a speech with the apposite title: “Statoil at the top of the world”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk biografisk leksikon, https://nbl.snl.no/Harald_Norvik Nor was he alone in this type of expansionist thinking – a general view prevailed at the time that internationalisation and growth were the only appropriate strategy for companies which wanted to survive.

Development of the NCS

Nevertheless, Statoil’s main activities under Norvik concentrated primarily on the NCS. Many large developments were under way there, such as Sleipner, the Statfjord satellites, Troll, Norne and Åsgard.

Many jobs went to Norwegian suppliers, but not before they had been subject to competitive tendering. Low and moderate oil prices in the 1990s, combined with government initiatives, pressured suppliers to standardise their production as far as possible in order to reduce costs.

Inspired by the UK, the Norsok project was initiated with involvement from both oil and supplier companies to make the NCS more competitive. It was strongly believed that industry standardisation and new modes of collaboration would improve efficiency. Statoil participated actively in many of the committees appointed in this process.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Nergaard, Arnfinn I, 2019, Getting down to it. 50 years of subsea success in Norway: 148-151.

Although Statoil was state-owned, and thereby regarded in some political circles as more bureaucratic than a private company, it worked just as efficiently as the privately owned foreign players. A report by consultants McKinsey in 1999 put Statoil in a good third place among 17 operators on the NCS and the UK continental shelf.

Basis for privatisation

Under Norvik, Statoil shifted to behaving like any other international oil company. An oil price slump in 1998-99 unleashed a wave of mergers among these firms. After BP joined with Amoco in 1998, it was on the cards that the collaboration deal with Statoil would expire – which happened in January 1999.

The company had to stand on its own two feet out in the wide world. To achieve greater freedom of action, Norvik proposed in a speech to the Norwegian Petroleum Society’s seminar in Sandefjord south of Oslo in January 1999 that the company should be privatised and freed from parliamentary control. He gradually gained acceptance for this proposal. Not only the Conservatives but also the Labour Party and the leadership of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) became positive. Norvik also wanted a large part of the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI), which was managed by a special department in Statoil, to be returned to the company. That would greatly strengthen its capital base, allowing it to assert itself among the bigger (merged) companies on the international stage. Such a strategic step faced greater opposition. Statoil could not simply help itself to the government’s revenues, it was asserted. This could have contributed to increased hostility to Norvik. But it was cost overruns on the NCS which ultimately meant he had to go.

Åsgard overruns

The Åsgard field in the Norwegian Sea was developed in the late 1990s as a pioneering subsea technology project. Along with the associated pipeline and the necessary expansions to receiving facilities at the Kårstø processing plant north of Stavanger, this presented major technical challenges. These resulted in a NOK 17 billion budget overrrun at a time when oil prices were almost down to USD 10 per barrel, which made the increase particularly difficult.

Strong criticism was levelled against the project, and the board was dismissed on 23 April 1999. Norvik resigned along with Terje Vareberg, his deputy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 182-185

In an interview with leading Oslo daily Aftenposten after the cost overruns and his departure, Norvik was asked about another controversial issue. He had called in public for a privatisation of Statoil – was it actually his job as CEO to ask for new owners? He replied: “Statoil is the people’s oil company, not the sitting government’s. I feel so strongly about this that I dared to issue a challenge by putting the issue on the agenda. I’m glad I’ve done so”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 25 April 1999.

It transpired that Norvik remained highly respected even after his departure both within Statoil and by the new board. He was asked to stay on until the autumn. The directors, with chair Ole Lund in the lead, demonstrated confidence in the course he had staked out. He was thereby able to set the agenda on important changes for the future.

Two big issues characterised this period. First came the collapse of Norway’s third oil company, Saga Petroleum, and the allocation of its holdings between Statoil and Norsk Hydro. Second, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy requested a report on a partial privatisation. This was ready on 13 August 1999, and proposed that the company should be partially privatised and that all or part of the SDFI’s assets should be “merged” into the company. These proposals marked the end point for Norvik’s time in Statoil. The course was set. It now fell to successor Olav Fjell to follow it up.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge, 2009, Til siste dråpe. Om oljens politiske økonomi: 257-263.

arrow_backArve Johnsen’s departureFrom Norol to Statoilarrow_forward