The gas pipeline system – arteries for exports

Southern California is perhaps most commonly associated with the film industry and sunny beaches.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For more extensive/general information on Norway’s pipeline system, see for example https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/production-and-exports/the-oil-and-gas-pipeline-system/, https://www.gassco.no/static/transport-3/#/, https://www.gassco.no/static/transport-3/#/timeline; Tønnesen, Harald and Hadland, Gunleiv, 2012, Oil and gas fields in Norway. Industrial heritage plan (2nd edn) Norwegian Petroleum Museum: 221-245; articles on Statpipe in the Norwegian Petroleum Museum’s Statfjord industrial heritage project; For network lengths and EU requirements, see https://www.gassco.no/static/transport-3/#/pipelines, all links accessed 26 April 2022. At the very end of the 19th century, however, it was also a pioneering area for taking the first small steps away from land to recover petroleum. The first pipeline was also soon installed in the same area, thereby realising the concept of an appropriate way to access the assets located beneath the seabed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Nergaard, Arnfinn, 2019, Getting down to it. 50 years of Norwegian subsea success, Wigestrand: 19; Gou, Boyun, Song, Shanhong, Chacko, Jacob and Ghalambor, Ali, 2005, Offshore Pipelines, Elsevier: 1.

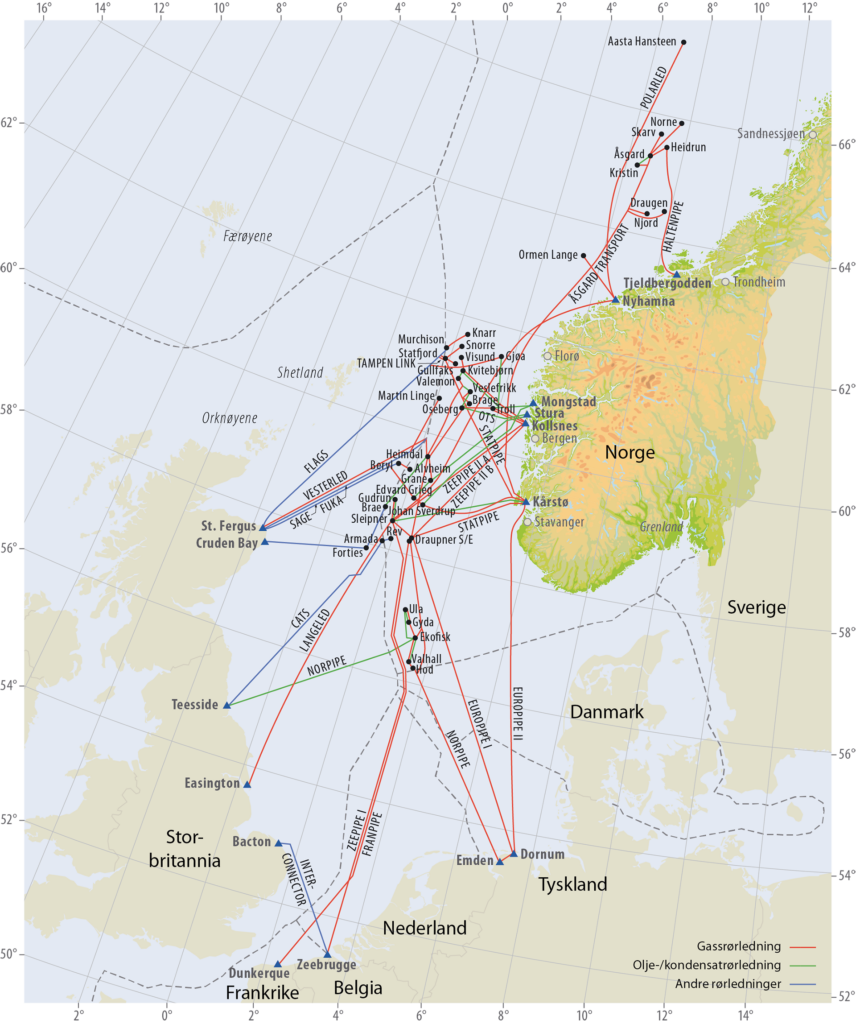

But many years were to pass before pipelines came to fulfil far bigger transport requirements on the bed of the NCS. Where gas is concerned, the Norpipe system is perhaps the best-known of Norway’s early pipelines. Running from Norway’s Ekofisk field to Emden in Germany, this became operational in 1977.

As new gas deposits were discovered, developed and brought on stream, an integrated gas pipeline system emerged on the NCS. A crucial reason was naturally meeting demand from the European energy market. But this network also resulted from dynamic interactions between guidelines set by national petroleum policy, innovative technology developments and demanding subsea topography.

Against that background, the following will look at some key pipelines with the emphasis on Statpipe and important export links with continental Europe.

Norwegian Trench

A recurring theme in the history of Norwegian gas pipelines has been the interaction between the politically desirable and the technologically possible. One of the best examples was the strong demand from politicians for petroleum resources to be landed in Norway. However, a formidable challenge stood in the way. The Norwegian Trench is an underwater valley separating much of Norway’s western coast from the considerably shallower parts of the North Sea. This feature is more than 300 metres deep in places. Statpipe was the name given to the major project which aimed to cross the Trench – twice – and carry gas to Europe.

Statpipe

The final political decision on this development and a Norwegian landfall was taken by the Storting (parliament) on 10 June 1981.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proceedings, 10 June 1981: 4171-4223, https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1980-81&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL566&pgid=c_1111&vt=c&did=DIVL134, accessed 26 April 2022. This followed a proposition (Bill) published on 8 April that year.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 102 (1980-1981) to the Storting, Ilandføring av gass fra Statfjordfeltet og Heimdalfeltet m.v., Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1980-81&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL163&pgid=b_0009, accessed 26 April 2022. The political process ahead of the decision had been so demanding that Statoil CEO Arve Johnsen wrote he “had never, in all the years I worked for Statoil, felt such huge pleasure as I did on leaving the Storting after the vote”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1990, Statoil-år. Gjennombrudd og vekst. 1978-1987, Gyldendal: 152. He has described the go-ahead as the most significant event in his time as CEO.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hadland, Gunleiv and Gjerde, Kristin Øye, Gas pipeline to continental Europe, https://statfjord.industriminne.no/en/2019/10/29/gas-pipeline-to-continental-europe/, accessed 26 April 2022.

Developing the Statpipe system primarily involved laying a pipeline from Statfjord (and other fields) to Kårstø north of Stavanger and a second line linking Kårstø with Norpipe at Ekofisk. That permitted a Norwegian landfall as well as onward delivery to Europe.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Heimdal was also included via a spur which tied into Statpipe’s Kårstø-Ekofisk leg at the Draupner S riser platform.

Operational from 1985, the overall Statpipe system was 892 kilometres long.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Statpipe”, Store norske leksikon, https://snl.no/Statpipe, accessed 22 March 2022; The overall length includes the Heimdal spur. Statoil played a key role in this project.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 102 (1980-1981), op.cit: 56. According to Johnsen, its unique aspect was that it not only involved laying a pipeline in deep water, but also set guidelines far into the future by “laying the basis for a gas pipeline infrastructure from the NCS which will have huge significance for Norway as a nation and for Statoil”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Quoted from Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Ryggvik, Helge, 2014, On the Edge, Under Water. Offshore Diving in Norway, Wigestrand: 182.

Statpipe demonstrated that pipelines could be laid in considerably deeper water than had previously been thought possible. At the same time, it was a breakthrough for the concept of an integrated system of gas pipelines on the NCS as well as realising the political desire for national control of Norway’s petroleum resources. And the system created a big export potential for gas to continental Europe – and particularly for the “volume” contracts, where several fields could be combined and supplement each other as suppliers.

Zeepipe and Europipe

The Norpipe and Statpipe projects had provided invaluable experience with North Sea topography and the art of selling gas. With that backing, and after talks with the British had failed, Norway’s gas sales personnel negotiated with the Europeans on delivering gas from the Troll and Sleipner fields. Developing Troll was strategically important for US attempts to curb Soviet gas sales to western Europe.

One challenge was again the Norwegian Trench. This time, however, the major difficulty was siting a huge concrete platform in more than 300 metres of water. The Trench was conquered yet again with Troll A, the world’s tallest moveable structure.

Developing Troll and Sleipner was important for the continued expansion of the pipeline network directed at continental Europe.

A key role in gas exports from these and other fields was played by the Zeepipe system – comprising sections I and IIA/B – and Europipe I and II. Zeepipe I runs from Sleipner to Zeebrugge in Belgium, and became operational in 1993. The last in this series to come on line was Europipe II, linking Kårstø with the terminal at Dornum in Germany.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.gassco.no/en/our-activities/pipelines-and-platforms/zeepipe/, https://www.gassco.no/en/our-activities/pipelines-and-platforms/europipe/ and https://www.gassco.no/en/our-activities/pipelines-and-platforms/europipe-II/; Tønnesen, Harald and Hadland, Gunleiv, op.cit: 228 and 230; Franpipe, which primarily delivers Troll gas to France, is 840 kilometres long and became operational in 1998, see Tønnesen, Harald and Hadland, Gunleiv: 229, and https://www.gassco.no/en/our-activities/pipelines-and-platforms/franpipe/, all accessed 26 April 2022.

Gassco

An ever-more extensive pipeline network enhances delivery flexibility, but also makes usage rights increasingly complex. In an effort to regulate stakeholder requirements, a gas negotiating committee (GFU) was established in 1986. To comply with the EU’s gas directive, however, this had to be replaced in 2001 by Gassco.

The latter company has the job of operating the gas transport network from the NCS on behalf of its owners. These have organised themselves in various joint ventures – Gassled, Haltenpipe, Valemon Rich Gas Pipeline, Knarr Gas Pipeline, Utsira High Gas Pipeline, Nyhamna, Polarled and Vestprosess DA. Equinor Energy’s stake in these constellations varies from zero for Knarr to 66.775 per cent in Valemon.

Gassco pursues a special operatorship, which includes regulating capacity in the pipeline network in the most integrated and efficient manner. Investment in pipelines and plants is financed by the owners, but Gassco carries out the work on their behalf as part of its normal operatorship.

Long-term approach

Gas exports call for a long-term approach. Big investment is required, including in pipeline systems. Seller and buyer are thereby literally bound together – and far more so than with oil sales where transport in many places is by tanker.

The ability to think strategically is crucial for achieving the highest possible financial gain in the long term for Norwegian society and the companies involved in recovering petroleum from the NCS. In such a perspective, Johnsen had every reason to be pleased at the Storting decision in June 1981. It opened an important chapter in Norwegian export history.

arrow_backCurbing the cash flowEquality and diversity in Equinorarrow_forward