Curbing the cash flow

When the Conservatives took over from Labour after the 1981 vote, the party wanted to reorganise Statoil in order to reduce the concentration of financial power in the company. The most important criticisms of its position in the Norwegian petroleum sector were that it:

- was too large and dominant

- threatened democracy by becoming a “state within the state”

- represented an intermingling of commerce and administration

- could create unhealthy dependencies in industry

- had so much cash that society’s resources could be wasted.

The cross-party consensus which had prevailed when Statoil was established had evaporated. It was beginning to dissipate as early as 1973, when Statoil was due to take over the state’s rights in the Frigg field. Conflicts arose over the company’s powers and the need for arrangements which ensured parliamentary management and control. [REMOVE]Fotnote: This article is based on Finn E Krogh, 1987, Reorganiseringen av Statoil. Intensjon, prosess og utfall – en analyse av beslutningsprosessen, MSc thesis, department of administration and organisation theory, University of Bergen.

During the second half of the 1970s, Conservative objections to Statoil’s status were elevated to the main plank in the party’s oil policy. However, Labour’s confidence in the company prevented the criticism reaching further than the Storting’s podium. The change of government in 1981 gave the Conservatives a real opportunity to win through with their critical views.

The term “clipping Statoil’s wings” reflects the main intention of the restructuring which was discussed and implemented in the early 1980s. Statoil was to be cut off from a large part of its revenues, which would instead be channeled directly into the government’s coffers. “Wing-clipping” provided a symbolic description of the issue and the decision process.

Future vision

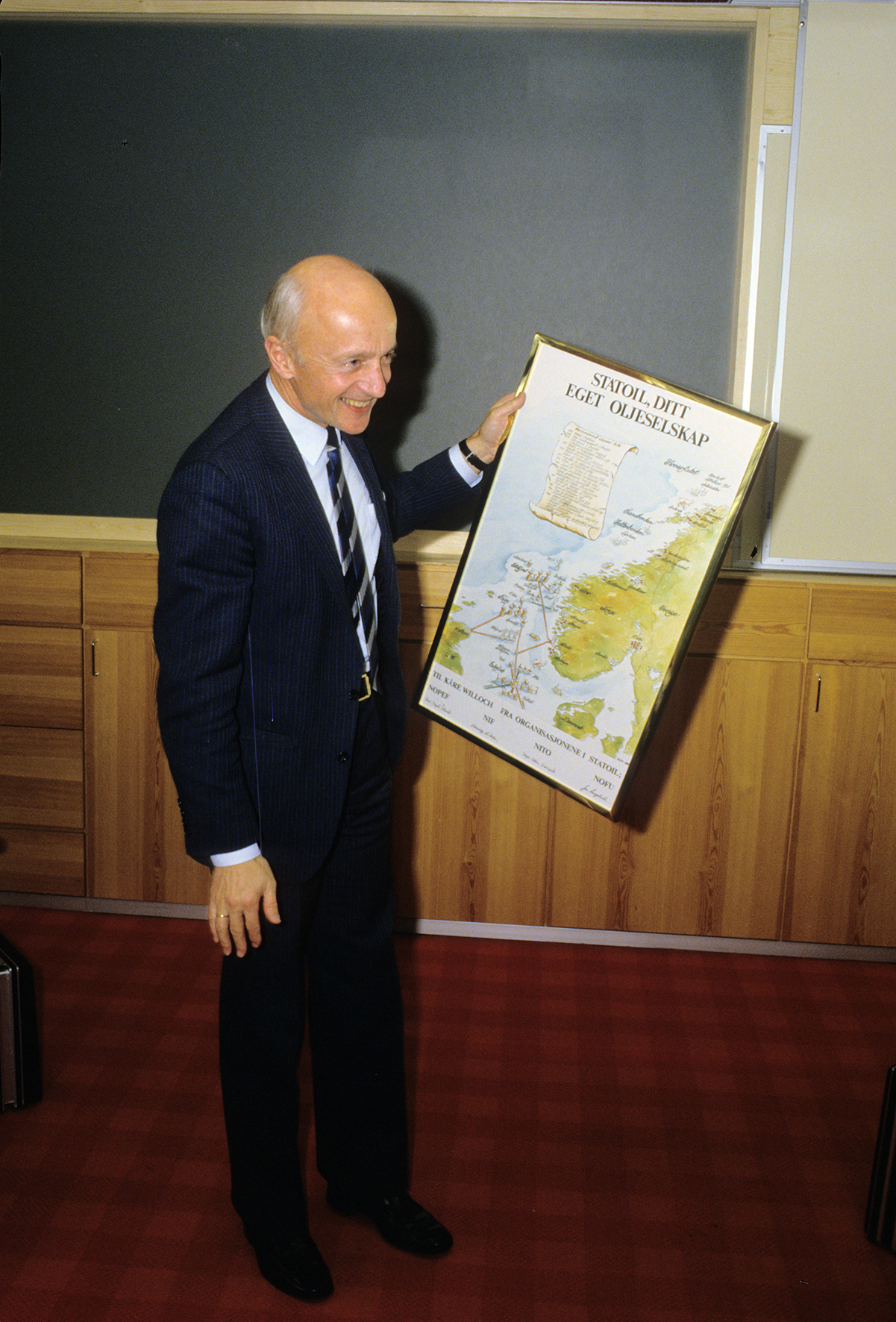

In the declaration of its intentions on taking office, the minority Conservative government headed by Kaare Willoch stated that it wanted to adopt measures which could change Statoil’s place in the organisational structure of the state. The aim was to prevent financial power becoming over-concentrated.

The political debate on Statoil’s future at this time was coloured by growth forecasts based on a high oil price and a steadily rising pace of offshore development. Such calculations suggested that the company might control a third of the government’s revenues by around 2000. This vision of state capitalism was presented by the Conservatives as a threat to political management of the petroleum sector. Support for this thinking from the Centre and Christian Democrat parties meant that a majority emerged in the Storting for reshaping Statoil’s role in the Norwegian oil sector.

Driving force

With new-won government power and a non-socialist majority at their back, the Conservatives went to work on realising their reform ideas. The party’s views on the organisational aspects of Norwegian petroleum policy had been made known in good time before the general election. Its oil policy committee published a report in May 1981 which countered Labour’s “perspective report” the year before. Highly critical of Statoil, the Conservative document outlined specific guidelines for restructuring the company.

Two prominent members of the committee, Vidkunn Hveding and Hans Henrik Ramm, were appointed minister and state secretary (junior minister) respectively at the petroleum and energy ministry (MPE) after the election. From these positions, they could decide for themselves on the guidelines for further reform work. This allowed the Conservatives’ leading oil policy experts to become key drivers of and players in the actual decision process.

Surprisingly substantial support for the ideas in the party’s counter-report was also shown by MPE staff. The civil servants had felt themselves to be ridden over roughshod on a number of occasions by Statoil’s ability to get issues approved at the political level without the ministry’s own assessments being taken into account. Over time, that had created a strained relationship between the company and the MPE. Officials at the latter therefore adopted a positive attitude to the restructuring plans floated by the Conservatives.

Proposals for reform

In February 1982, the government appointed a commission chaired by Supreme Court judge Jens Christian Mellbye to study options for reforming the existing organisational structure. Its mandate was tightly formulated and closely related to the Conservative oil policy programme.

One assumption was that overall government revenues – received directly and via Statoil – were not to be reduced by comparison with the prevailing system. Nor were the state’s rights – financial and otherwise – to be reduced. In practice, this meant that the Mellbye commission’s recommendations had to be kept within the parameters of the government’s oil policy goals as formulated in the Conservative counter-report. This allowed the ruling party to maintain a high level of control over the actual decision process. Labour, for its part, characterised the whole exercise as a “commissioned work”.

Key proposals

After a year’s work, the Mellbye commission produced a unanimous report on the organisation of state participation in the petroleum sector (Norwegian Official Reports NOU 1983:16). Its conclusions can be summed up in the following key points:

- a substantial proportion of Statoil’s revenues should be channelled directly to the Treasury

- Statoil’s powers in the operative joint ventures should be rebalanced (removal of its veto power)

- the state’s other instruments – the MPE and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) – should be strengthened to ensure increased control by government and parliament

- measures should be proposed for strengthening Norway’s other oil companies – Norsk Hydro and Saga Petroleum.

The commission proposed that the recommended changes should also cover production licences already awarded. Without such retroactive effect, the new organisational structure would not have practical consequences until far into the future.

Nothing specific was said about the size of the state’s direct share in the various licences. This was seen as a matter for political judgement – and thereby for making the new structure flexible in relation to changing governments.

Amputation claim

These proposals were well received in government circles. Ramm, who had been a leading Conservative player throughout the process, expressed great satisfaction that the conclusions were clearly within the mandate. Statoil’s management had maintained a low profile throughout the commission’s work. Nor was it willing to make any official comment when the recommendations became known. Neither the company’s CEO, Arve Johnsen, nor chair Finn Lied were prepared to express any views on the report.

However, Labour daily Arbeiderbladet had inside information about reactions within Statoil, and brushed aside any doubts about the company’s view of the reform plans. An article the day after the Mellbye report appeared described the mood:

“Nobody in Statoil’s management wants to comment on the recommendations, but Arbeiderbladet has been told that this is not a wing-clipping – it is an amputation”.

[People] in the state oil company say bluntly that they regard the report as a direct vote of no confidence in Statoil’s ability to manage the assets which the political authorities have so far decided should belong to the company. Many in the company refuse to believe that the political authorities, including the Conservative government, will go as far as is proposed.

Party-political clash

None of the reactions to the Mellbye commission’s report can be considered surprising. On the contrary, the positions adopted were more a confirmation of the battle lines which had become entrenched since Statoil reform emerged on the political agenda.

This remained a controversial issue over the three years it moved in and out of the political arena. Labour strongly opposed the Conservative plans to clip Statoil’s wings, arguing that they would weaken the company and leave it poorly equipped to compete with the foreign oil majors. In addition, the dispute activated key ideological divisions between Conservative and Labour views of the public sector’s involvement in commercial activities and the extent of state participation in the oil sector.

During the summer of 1983, the minority Conservative government was broadened into a majority three-party non-socialist coalition with the Centre and Christian Democrat parties. The Statoil reform thereby became a subject of talks between the three governing parties on the one hand and Labour on the other. However, few signs suggested that it would be possible to reach a negotiated solution.

Reform measures

On the basis of the Mellbye commission’s recommendations, and despite many negative responses in the public consultation, the government proposed two main changes aimed at limiting Statoil’s financial expansion and its potential power over other players in the Norwegian oil sector.

The first involved splitting its revenue flow into separate state and company shares. This would give the government direct control over a certain percentage of current gross revenues and expenses. Known as the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI), the size of this share would vary from field to field. In the Gullfaks and Troll licences, however, the government proposed taking over no less than 73 per cent of the 85 per cent interest originally awarded to Statoil.

Second, the voting rules were to be modified in certain licences so that Statoil no longer had a majority and sole veto. In the future, it would have to collaborate with one or more of the other licensees in order for decisions to be reached.

These proposals concentrated on Statoil’s operating parameters. Channelling the bulk of the cash flow directly to the Treasury would avoid the “problem” of capital accumulating in the company. And amending the voting rules altered the decision process in the individual licence.

No measures were proposed to strengthen overall political control of Statoil. Such solutions were excluded at an early stage out of consideration for the company’s commercial freedom of action and the desire to emphasise the dividing line between business and administration.

Labour rejected these proposals, and the stage was thereby set for an oil policy schism in the Storting if the government opted to impose the reform measures as a pure majority decision. The conflict over clipping Statoil’s wings threatened to bring an end to a long era of broad political consensus over key issues related to the Norwegian oil industry.

Internal opposition

But the question of reorganising Statoil also encountered strong opposition from within the non-socialist alliance. Key politicians in both the Centre and Christian Democrat parties were critical to large parts of the reform proposals. That applied not least to Finn T Isaksen, the Centre Party agriculture minister who had previously been a Statoil director. He argued strongly in favour of reducing the financial consequences of a possible reform. However, the strongest internal opposition came from what might be called the “west Norwegian wing” of the Conservative Party, with Arne Rettedal, minister of local government and labour and prominent Stavanger politician, as its leading spokesperson.

In February 1984, Rettedal wrote a personal memorandum to prime minister Willoch where he accepted the idea of an SDFI but requested that it should not be given retroactive effect. In practice, that would allow Statoil to retain its big holdings in Statfjord, Heimdal and Gullfaks. These internal fissures within the Conservatives were not linked solely to Stavanger and Statoil’s home ground. They also reflected divisions over ideology and principles within the party.

The views of the most eager reform proponents on its ranks were formulated by relatively young, academically educated politicians. Their leading representatives were Ramm and Terje Osmundsen, the prime minister’s personal secretary. Their primary desire was to curb Statoil’s growth out of concern over a potential concentration of power and a lack of democratic control.

Invitation to collaborate

Shortly before the Storting was due to debate the Statoil reform, the party battle lines were still well entrenched. The government and much of the political community had discounted the possibility of finding a compromise. It was in these conditions, that Labour wrote to Willoch on 12 March 1984 and invited him to a collaboration over the issue of reorganising the state oil company.

Labour leader Gro Harlem Brundtland held a press conference with Finn Kristensen, the party’s oil policy spokesperson, after this invitation became known. They rejected any suggestion that the initiative could be interpreted as approval of the Conservative intentions to clip Statoil’s wings. Instead, its purpose was said to be to open the way to a dialogue on the reform issue which could help to maintain the broad consensus over Norwegian oil policy.

Statoil compromise

When Labour took its negotiation initiative in the spring of 1984, the Statoil reform issue had been affecting the oil-policy debate for three years. But the invitation was well received in government circles. Willoch and the parliamentary leaders of the centrist parties in the coalition regarded it as positive for securing a long-term and stable oil policy. A series of four top-level political meetings on the reforms followed. Since little time was available before the issue had to be submitted to the Storting, they were squeezed into a 14-day window.

These efforts to find a compromise must be regarded as extraordinary in a Norwegian context. Seldom have attempts been made to resolve such an important and controversial single issue in so short a time through such concentrated negotiations. Labour had to make the biggest concessions, since the government was unwilling to give way on the issues of principal in its proposals. The solution agreed between the parties was fundamentally the same as that proposed by the Mellbye commission, but with one key exception – Statfjord was excluded from the new provisions.

Commentators expressed astonishment at this outcome. It was considered a political feat that Labour and the non-socialists had managed to negotiate a compromise solution when their original positions had been so far apart. Two weeks later, on 8 June 1984, the Storting voted unanimously to implement the report. The new organisational framework took effect on 1 January 1985.

Statfjord effect

Splitting income and expenses into company and government flows was intended to separate Statoil from much of the oil revenues passing through it and slow its expected expansion. The effect sought was that Statoil would have to tailor its future activities to a more restricted financial base. Such an outcome would have been attainable if the reform had been implemented to the full. But Statfjord was excluded. This field had been Statoil’s most important source of income throughout, and would remain so for a long time to come. In addition, its costs were so low that the financial return from Statfjord remained relatively good even with a low oil price. That sharply reduced the immediate financial impact of the reform measures.

Most of the other fields where the SDFI was introduced had a weaker earnings potential and were more exposed to oil price fluctuations. Collectively, these factors created the Statfjord effect – Statoil could continue to milk that field while the government was left with the bulk of the expenses in the most cost-intensive development projects, such as Heimdal, Oseberg and Gullfaks.

Combined with the dramatic oil price slump in 1986, this put the government an unanticipated position. The desire for better control of the sector’s enormous revenues became just as much a responsibility for the equally huge expenditures.

The cash flow to the government’s coffers proved much smaller than expected, and the goal of limiting the Statoil group’s cash mountain to the benefit of the state was actually reversed for a time. That demonstrates how changes to two significant preconditions for the Statoil reform – a consistent sharing of the cash flow on all the fields and a stable oil price – led to an unexpected outcome.

In the short term, this proved expensive for the government and correspondingly beneficial for Statoil. It therefore took many years before the expected financial effects of the new organisational structure were secured.

Organisational milestone

The debate over clipping Statoil’s wings exposed clear political divisions. However, the negotiations which produced the 1984 compromise can be seen as a consolidation of important principles in Norwegian oil policy. After a period of sharp party-political conflict, calm was established around Statoil’s role. The solution adopted has subsequently been cited as an organisational milestone for Norwegian state participation in the petroleum sector, and the intentions of the compromise have been respected by governments of varying political hue.

arrow_backVictory over Mongstad expansionThe gas pipeline system – arteries for exportsarrow_forward