Troll gas to the continent

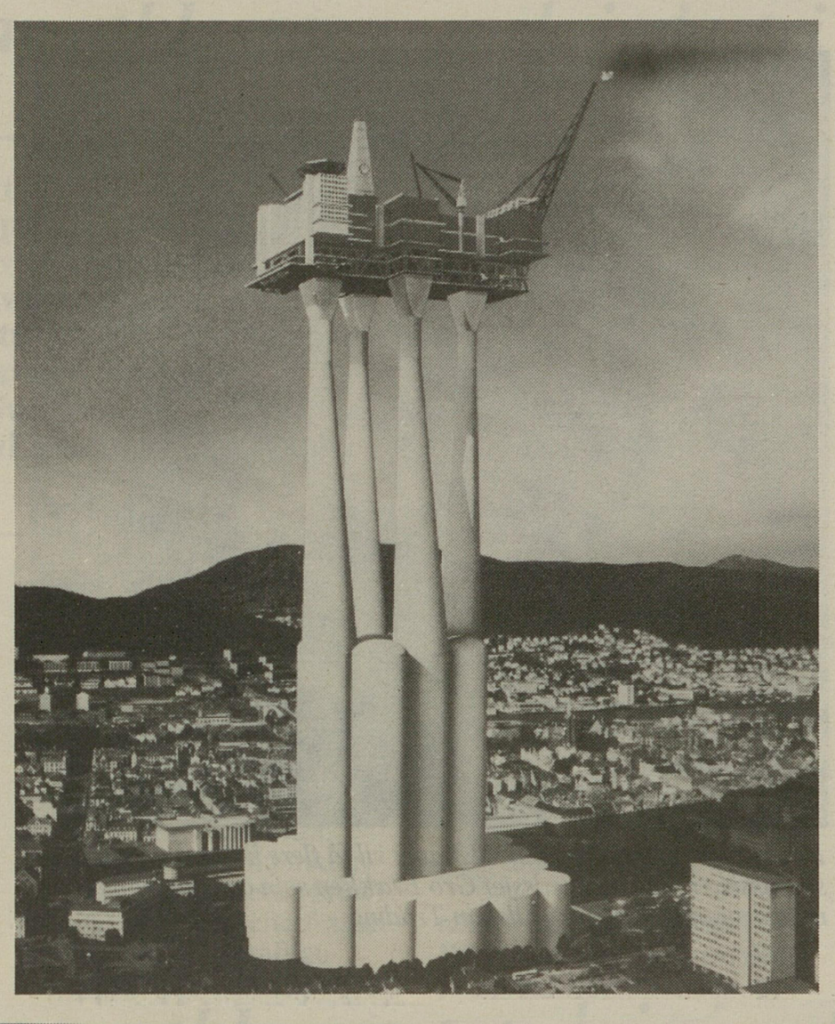

Several aspects of Troll can seem spectacular. For a start, it is unique on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) by holding some 40 per cent of the gas reserves. And it is also one of Norway’s very largest oil fields.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The Troll field and the Troll A, B and C platforms,https://www.equinor.com/energy/troll, accessed 26 April 2022. Similarly, building the Troll A platform tested the limits of concrete as a building material.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sandberg, Finn Harald, The Condeep story, https://draugen.industriminne.no/en/2018/05/14/working-on-the-slip/, accessed 26 April 2022. This structure represented the high point of about two decades dominated on the NCS by large fixed Condeep installations.

Troll was also a source of conflict. The size of its reservoir and the timing of its discovery meant that the field became a pawn in the Cold War rivalry between the superpowers. Furthermore, the wide geographical extent of the field created friction between the companies involved, which held differing interests in some or all of the various blocks.

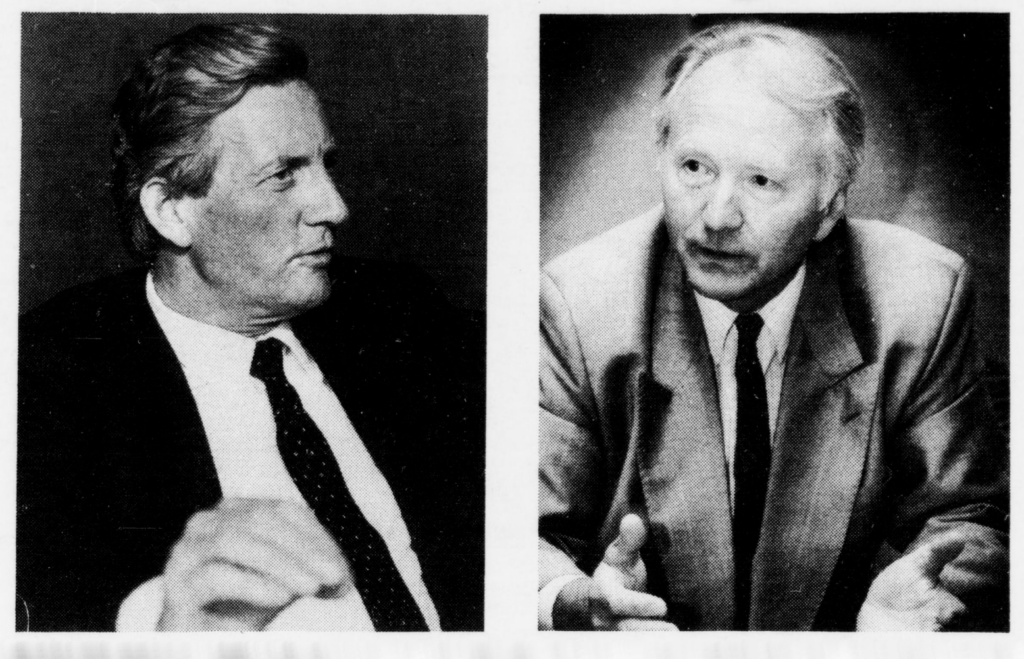

With CEO Arve Johnsen at the helm, Statoil became responsible for gas production from Troll, and took the lead on the Norwegian side in gas sales negotiations with European buyers. Other participants were Conoco, Mobil, Norsk Hydro, Norske Shell and Saga Petroleum.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1990, Statoil-år. Gjennombrudd og vekst. 1978-1987. Gyldendal: 259; Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, 1996, Troll. Gas for generations, Shell: 90.

European energy strategies

This Troll group dealt with a consortium of companies from West Germany, France, the Netherlands and Belgium.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve,: 259, Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar: 90. The Europeans had a complicated basis for these talks, partly because they represented different countries. But they also shared a number of perceptions based on their energy position.

Where oil was concerned, the primary consideration was import strategies. The way the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) had behaved earlier, particularly during the 1973 oil crisis, had been poorly received by the Europeans. One way for the latter to deal with this was to increase oil purchases from other suppliers.

Another was to make greater use of other energy sources. Along with coal and nuclear power, natural gas was an option. During the Cold War, however, west European dependence on gas had a particular strategic drawback – particularly to American eyes – because it could strengthen the Soviet Union.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar: 88. That context opened opportunities for Norway as a gas exporter.

Buyer’s market

The chief negotiators over the Troll gas were Johnsen and Klaus Liesen at Ruhrgas AG. This pair had also reached agreement earlier on conditions for Norwegian gas deliveries to the continent in an export agreement covering Statfjord, Heimdal and Gullfaks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 90. A seller’s market had prevailed then, and a high gas price was secured.

Despite being on the opposite side of the negotiating table, Johnsen undoubtedly respected Liesen. He described the German as “systematic, persevering and clear-thinking” and as “the ablest gas buyer I have met”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, op.cit: 258.

One concern among the buyers was that technical problems or labour disputes on the NCS could interrupt deliveries. This was overcome by the sellers funding gas storage in large caverns in Lower Saxony, which could hold a 14-day buffer stock.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, op.cit: 101; Board minutes, Statoil, 26 June 1986, item 6/86-9, 9.3. (Source: SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Aba/L0003: Styremøteprotokoller, 27.08.1985 til 28/29.06.1990. Dokumentliste Styret og Representantskapet 1974 til 1979., 1974-1990.)

Another important element in the negotiations involved incorporating gas from Norway’s Sleipner East field in the agreement. That made it possible to begin deliveries as early as the autumn of 1993, instead of three years later with Troll alone.

These technical delivery challenges were additional to the issue of price. Market realities indicated that gas had become significantly cheaper since Johnsen and Liesen’s previous deal. An important basis for moving the Troll talks forward was promises by the sellers on price reductions compared with that agreement. The buyers eventually made this a condition of reaching a settlement.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, op.cit: 108.

Profitable day

Statoil took the view that avoiding lengthy negotiations was in its interest, since other potential suppliers of cheap gas to western Europe’s industries and householders were lurking in the wings.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 107-108.

Early on 30 May 1986, however, nobody knew how the day would pan out – not even Johnsen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, op.cit: 264. He explained the uncertainty thus: “It was not always easy to keep order in the ranks … and there could at times be more than 30 people all told in the negotiating room”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 258. On this morning, in fact, no less than 40 people from both sides were assembled at Statoil’s Forus head office outside Stavanger.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 6/7 1986, “Norges-historiens største eksportkontrakt er klar”; Johnsen, Arve, op.cit: 264.

By the afternoon, price was the last issue to be settled. Johnsen began to envisage that it might be possible to reach agreement within the next few hours.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, op.cit: 264.

Late that evening, the two sides finally agreed on the price and a contract value of roughly NOK 500 billion. Statoil’s Status house journal reported the CEO’s expression after an event which needed no words there and then: “At 23.16, Johnsen appears. His smile says it all. Agreement has been reached”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, op.cit.

The gas sales deal was approved by Statoil’s board in September 1986.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board minutes, Statoil, 11 September 1986, item 8/86-2. (Source: SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Aba/L0003: Styremøteprotokoller, 27.08.1985 til 28/29.06.1990. Dokumentliste Styret og Representantskapet 1974 til 1979., 1974-1990.) That December, the Storting (parliament) agreed on the development of Troll and Sleipner East with Statoil as a participant.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 15 December 1986: 1792-93. https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1986-87&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL14&pgid=b_0368. accessed 26 April 2022.

Long-term significance

The Troll gas sales agreements not only secured massive revenues for the sellers, but also influenced developments on the NCS and oil policy in Norway for a long time to come.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk oljehistorie, Norwegian Petroleum Society, Leseselskapet: 273. An interesting aspect was that they were to a great extent supply contracts which covered a specified volume, regardless of which field(s) it came from. In this case, Sleipner East gas was delivered to Europe before Troll came on stream.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 1 (1986-87) to the Storting, annex 13, Utbygging og ilandføring av petroleum fra Trollfeltet og Sleipner Østfeltet m.v: 7 (8). Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1986-87&paid=1&wid=c&psid=DIVL2349&pgid=c_1027. accessed 26 April 2022.

In a broader perspective, it has been argued that “the negotiations [concerned] a system which would reinforce the position of gas as a principal source of energy in Europe for the 21st century”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Borchgrevink, Aage S, 2019, Giganten, Kagge: 171.

Given such assessments, it is difficult to over-exaggerate the importance of the biggest export agreement in Norwegian history.

However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, together (and partly in combination) with the dynamic development of European energy strategies, means it is difficult to make precise long-term forecasts of the importance of Norwegian gas exports.

arrow_backBattle over operating TrollTommeliten – valuable subsea experiencearrow_forward