Equality and diversity in Equinor

Over the decades, equality and diversity in Statoil/Equinor have gone from an ambition and a goal to being presented as a competitive advantage and a strategic tool for the group. The company has pursued various measures over the years to promote equality. Since these have largely complied with government approaches in form and purpose, it is natural to make mention of these as well.

This article begins with some background on the issues related to gender, equality and diversity in the petroleum sector, and then addresses developments at Statoil in the 1980s, the 1990s, and the years since 2000.

Gender and equality in the petroleum sector

Considerable developments have occurred over the years in female educational choices, the type of jobs held by women and men and, not least, attitudes related to this in Statoil, the petroleum sector, and industry and society in general. Women in the oil and gas industry have largely made their career choices along traditional lines. From the company’s foundation in 1972, women in Statoil worked in administration and catering on land. Only men were employed offshore in the North Sea to start with. Exploration drilling or petroleum production were still regarded as a male preserve when oil began flowing from the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) in the early 1970s. It involved dirty, rough and physically demanding shift work. Eventually, however, women began to get jobs on offshore installations. Some were employed in catering and others as medics. Females were also out on deck or in other technical occupations. The common denominator for everyone who started doing tours offshore in the 1970s was that they came to workplaces built by men for men.

Early in the history of Norway’s petroleum sector, then, women often found themselves in caring occupations and lacked the same opportunities for promotion as their male colleagues. The reasons for the gender imbalance in the Norwegian oil business during the 1970s were manifold and complex. Over the course of that decade, however, the demand for equal opportunities for men and women became clearer both politically and among ordinary people. Norway’s Gender Equality Council was set up in 1972 and the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act followed in 1978. In step with this trend, pressure for women’s rights also grew in the country’s offshore sector. Temporary regulations for NCS living quarters issued by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) in 1979 required operators to provide accommodation and toilet facilities for both women and men on platforms. Until then, the safety regulations adopted in 1976 for the offshore industry only covered “the necessary rooms for quartering people staying on the facilities at any given time”, without taking explicit account of gender.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Temporary regulations for living quarters on production facilities, etc, Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, 1979; Safety regulations for production, etc, of underwater petroleum deposits, Royal Decree, 7 July 1976, Ministry of Industry and Trade.

With the quarters regulations, the NPD became one of the bodies which put the greatest pressure on the Norwegian oil sector to make provision for women. These rules became an important step in equality policy for the industry, and formally opened the doors for females offshore. However, the NPD’s role must not be exaggerated. It made no active efforts to promote equal opportunities, but followed up the provisions of the Equality and Working Environment Acts related to providing for both genders on the NCS. However, considerable work remained to be done on attitudes to female participation in the sector.

While much has happened over the decades, the oil industry remains male dominated right up to the present day – particularly offshore. As recently as 2017, barely 11 per cent of the NCS workforce was female. No less than 29 per cent of these women worked in catering, compared with only four per cent of male personnel.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Fjelldal, Øystein and Blomgren, Atle, Kartlegging av offshoreansatte 2017, Report 10-2019, Norwegian Research Centre (Norce), Stavanger, 2019. At the same time, recent reputational and recruitment campaigns from the oil companies reveal that they want to present a working life offshore (as in the rest of the petroleum industry) with female managers and role models who are climbing the career ladder. The statistics show that, although the share of women on the NCS lies at a stable 10 per cent, the female proportion of Norway’s petroleum sector workforce has risen overall from about 16 per cent in 2003 to 20 per cent in 2016. Growth has been particularly strong among women with higher education, who accounted in 2016 for around 60 per cent of females in petroleum-related jobs. The comparable figure for males was 36 per cent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.ssb.no/arbeid-og-lonn/artikler-og-publikasjoner/sysselsatte-i-petroleumsnaeringene-og-relaterte-naeringer-2016.

Big differences will naturally exist between workplaces in offices, onshore plants and offshore facilities. But the trend seems to be that, while the industry has succeeded to a great extent in recruiting highly educated women to jobs on land, staffing offshore has largely remained male-dominated and divided along gender lines. Women can naturally be found as offshore installation managers, and hold other technical positions on the NCS. Generally speaking, however, highly educated females spend time offshore for periods as a stage in their careers. They do not remain in a job offshore long enough to acquire the same experience as those who occupy other types of position on a permanent basis. Earlier research shows that women with higher education and holding senior posts in the petroleum industry have found they can exert good influence over their own jobs and face little in the way of negative attitudes. But others say it has been important to “under-communicate their femininity”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ervik, Ragna M L, Man må passe på. Om kvinneidentitet i et mannsmiljø. En studie om kvinnene på Ekofisk. Master’s thesis in social anthropology, University of Bergen, 2004. In contrast, those who work in catering or operational jobs generally remain in the same position on the same facility over a long period. Naturally, however, this picture conceals nuances and a wide range of personal experiences.

After this general look at gender equality in the Norwegian petroleum industry, the question is how this aspect has developed in Statoil.

1980s: Aligning with government initiatives

When Statoil was established, gender equality had not become a particular political issue in Norway. As mentioned above, it first began to acquire prominence in the late 1970s. The company was state-owned and aligned with official policies and regulations. Legislation, regulations and measures imposed by government were significant for work on equality. These efforts began formally at Statoil in 1980, precisely in response to the 1978 Equality Act.

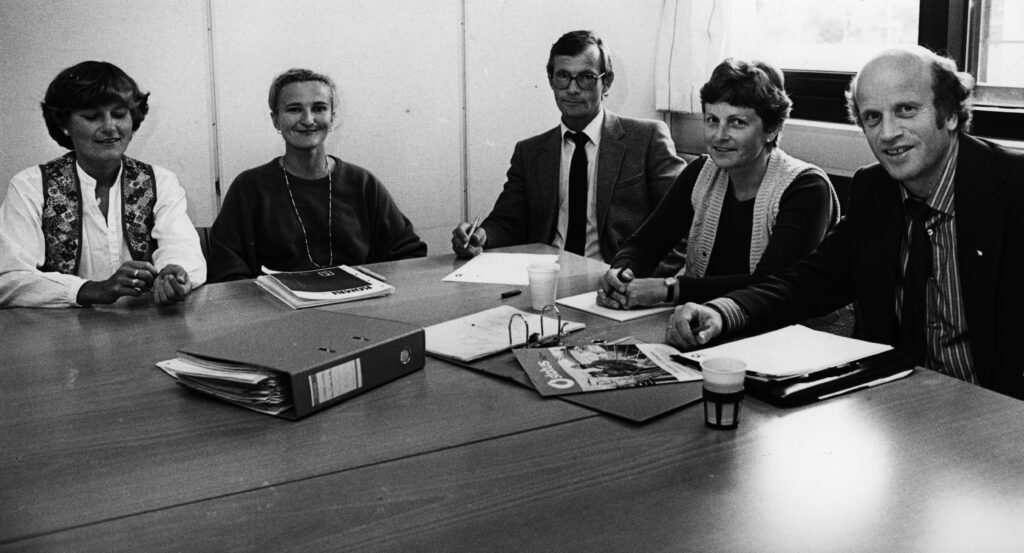

[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/likestillingsloven/id454568/. In a 1985 equality handbook, the company made it clear that policy in this area was based on the Act. The signs are that legislation and government policies both provided guidance for and applied pressure on its equality work.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Larsen, Eirinn, “Fra likestilling til mangfold. To tiår med kvinner og ledelse i bedriften”, Nytt norsk tidsskrift 17, 2, 1999: 114-125. As the 1980s progressed, the handbook was supplemented by various action programmes and an equal opportunities committee was established.

Statoil regarded it as “valuable in a personnel policy context that opportunities, responsibilities and tasks are evenly distributed between female and male employees”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoils likestillingshåndbok, SAST/A-101656/0001/P/Pb/L001, 1985. Furthermore, this applied clearly to both management posts and disciplines where women were under-represented. An internal project group appointed by management had already produced a report on getting more women into leading posts in Statoil. Many different measures were adopted from the early 1980s, such as executive officer courses, scholarships, active recruitment, job reviews, courses and educational offers and traineeships for women.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sletbakken Hauglie, Vilde, Da likestilling ble et Statoilanliggende. Om likestillingsarbeidet i Statoil fra 1972 til i dag, Master’s thesis in history, University of Oslo, 2018.

Individuals in the company are often highlighted for their contribution to equality work – including Arve Johnsen, who was CEO from 1972 to 1988. The dedicated equal opportunities committee established in Statoil during the first half of the 1980s was intended to work on equal opportunities issues, generally promote such cases and provide information. However, various aspects of its work came in for criticism. It was said that these efforts were not very visible to employees, that management paid them less attention than was desirable, and that the committee was ineffective. Critics claimed that gender equality efforts in the company were solely a symbolic gesture to legitimise that Statoil took this issue seriously to the outside world. The committee produced many written declarations of intent on equality, with associated offers and measures which many women took advantage of. While the company sought to live up to expectations and legal requirements, progress seems to have been slow in the 1980s.

Statoil’s early equality measures took little account of the differences between land and offshore in the challenges faced in this area. Analyses show that attention was primarily concentrated onshore, where the majority of the women employees worked. Action was tailored to office conditions on land, presumably because these offered greater opportunities for success. Very few women worked offshore at the time, and the likelihood of breakthroughs there was smaller. Since a few years also passed before Statoil even had female employees on the NCS, it is not unnatural that equality measures were concentrated on land. But sources nevertheless claim that nothing was done to promote equal opportunities offshore in the 1980s, and that a long time passed before provision for females was made on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. A film highlighting that the NCS was also for women illustrated how pregnant women offshore were sent ashore early, in the best case to work on land (if they were employed by an operator like Statoil) and otherwise at risk of being laid off without pay (if they worked for a contractor). Making paid maternity leave a legal requirement in Norway in 1987 improved this position.

1990s: Tensions in equality work

Little attention is devoted to equal opportunities in Statoil’s annual reports from the 1990s but, to the extent that it receives a mention, women in management are the focus. Increasing the proportion of female managers appears to characterise equality work in this decade. A specific target for the number of women in management was expressly given in an action programme for 1992-93. The goal was a 15 per cent female share by 2000, which rose to 20 per cent in the 1994-95 programme. The statistics showed a small rise in female managers, from 9.5 in 1991 to over 10 per cent in 1993.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Likestillingsrapport for perioden 1991-1993, SAST/A-101656/0001/P/Pb/L0005. In this respect, Statoil was on a par with Norwegian industry as a whole. Where establishing a equal opportunities committee and an action plan was concerned, however, it ranked as an early adopter compared with other companies in the petroleum sector.

The management may have given serious thought to the criticism that equality work had too low a profile. Statoil established an equal opportunities prize in 1992 with the goal of strengthening such efforts. Regardless of many good intentions as the 1990s progressed, however, tensions arose between management and employee groups over equality. Many people were dissatisfied that the original objective of equal opportunities for personnel in general had been replaced by a concentration on female managers. Disagreements about equality appear to have prevailed between the leadership and a number of employees for much of the 1990s.

The equal opportunities committee was discontinued in 1994 on the grounds that gender equality prevailed at all levels in the company, and that winding up this body would promote further work in the area. In that respect, Statoil formed part of an international equal opportunities trend in the second half of the 1990s known as “gender mainstreaming”. This involved incorporating equality as a natural element at all levels of an organisation. Disbanding the committee thereby signalled that it had outlived its role and that work on gender equality was ripe for a change.

At the same time, several rounds of reorganisation and cost-cutting measures were conducted in Statoil during the 1990s. Examples exist that these led to equal opportunities being sidelined and resulted in fewer women being placed in senior positions. However, other instances indicate that the proportion of female managers rose despite workforce downsizing.

Such individual cases illustrate that equality work in Statoil was characterised more by chance and decisions on individual cases than by the overall policy in this area expressed externally.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Larsen, Eirinn, “Fra likestilling til mangfold. To tiår med kvinner og ledelse i bedriften”, Nytt norsk tidsskrift 17, 2, 1999: 114-125. It seems that reorganisation, partial privatisation, changed market conditions and increased globalisation in the late 1990s and into the 2000s put efforts to promote equal opportunities in the company to some extent on hold.

Such conditions contributed to changes in the form and goal of gender equality work in Statoil. Discontinuing the equal opportunities committee in 1994 appears to have caused little noise.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sletbakken Hauglie, Vilde, Da likestilling ble et Statoilanliggende. Om likestillingsarbeidet i Statoil fra 1972 til i dag, Master’s thesis in history, University of Oslo, 2018. But how far the general and far-reaching approach called for by the national and international trend towards gender mainstreaming was subsequently pursued by the organisation is uncertain.

2000s: Adjusting to the market and internationalisation

In the early 2000s, Statoil concentrated its attention in working for both gender equality and diversity. This was in line with a general trend in Norwegian society.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nrk.no/norge/–norge-en-likestillingssinke-1.511472. However, many employees were unclear over what the group’s equal opportunities measures involved in practice and what goals were being pursued. Equality and the gender balance were once again included Statoil’s annual reports from 2002, but were then presented as a competitive advantage. This probably reflected an industrial policy promoted politically as well as the change in Statoil’s ownership and increased internationalisation/globalisation.

An important direction taken by work on equal opportunities in Statoil during the 2000s, as in many other companies nationally and internationally, was that gender equality became part of the diversity concept. This was made explicit in the group by making direct mention of diversity in annual reports from 2002, with no reference to gender equality from 2008 to 2017.

“Diversity” as a concept illustrated how equal opportunities had acquired a wider meaning in Statoil as well as in society as a whole, in other countries and in much of the international business community. That meant a transition from concentrating on gender to an expanded concept of equality which also embraced such other characteristics as nationality, culture and language. A contributory cause of this shift was the partial privatisation of the group. To succeed, this change in ownership meant that the business community’s principles for equality and profitability had to weigh heavily in strategic documents and plans. Goals on diversity and equal opportunities were actively deployed as arguments for pursuing increased profitability and competitiveness. As the 2000s progressed, a number of legislative amendments also contributed to this trend. The most important was undoubtedly the new legal provision on gender quotas in 2003, which compelled limited companies to improve the gender balance on their board of directors.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Teigen, Mari, Kvotering og kontrovers – virkemidler i likestillingspolitikken, Pax Forlag, Oslo, 2003.

All in all, developments since then been characterised by the “equality” concept acquiring a diverse content, and by “gender equality” no longer being synonymous with the modern sense of this term. Given developments in recent years, Statoil has had an ambition to work for diversity at every level, but no longer pursues specific goals as it did where equal opportunities were originally concerned. The strategy in today’s Equinor is to achieve even greater diversity and to get better at releasing its value in order to create an inclusive workplace. From that perspective, equality has become not only an ambition but also a symbol and strategic tool. With the 2018 change of name to Equinor, with its connotations of equality and equal status, it is natural to think that the group took yet another step towards establishing equality and diversity as brands and competitive advantages.

arrow_backThe gas pipeline system – arteries for exportsExpansion in Scandinaviaarrow_forward