Equinor at 50

With Arve Johnsen as CEO from 1 December 1972, a cigar box to hold its petty cash and a share capital of NOK 5 million, the company was intended to ensure Norwegian participation in oil production from the start and to build up expertise which could form the basis for a national petroleum industry.

Over the course of its first half-century, six Norwegians have served as CEO – Johnsen, Harald Norvik, Olav Fjell, Helge Lund, Eldar Sætre and Anders Opedal. Each has had their own strategies, which have left strong marks on the company.

Growth and wing-clipping

Inspired by studies in the USA and the business model applied by oil magnate John D Rockefeller, energetic Johnsen aimed to build an enterprise involved along the whole value chain from exploration and production to selling refined products.

Statoil quickly became Norway’s largest oil company. Its first licence holding was in the Statfjord field, which came on stream in 1979. Taking over the Statfjord operatorship from Mobil in 1987, construction of the Statpipe pipeline and the inauguration of Gullfaks as the first all-Norwegian and own-operated field were highlights in this period. The cost overruns with the Mongstad refinery expansion marked the big downturn.

This growth was not without opposition in political circles. While Johnsen’s approach was strongly supported by the Labour Party, it encountered substantial hostility on the non-socialist side – particularly from the Conservatives. When the latter took office under Kåre Willoch after the 1981 general election, a reform process known as “clipping the wings” of Statoil was initiated. This led to the 1985 introduction of the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI) in oil and gas fields. That restricted Statoil’s freedom of manoeuvre – although it was important for the company’s growth that Statfjord was excluded from the SDFI scheme.

Outwards, northwards and deeper

The more considered strategist Norvik took over as CEO in 1988. He wanted to “depoliticise” the company and move it in a freer and more commercial direction. An internationalisation of Statoil got going seriously during his time. A strategic alliance with BP in 1990 gave the company exploration and production footholds in west Africa (Angola and Nigeria), Asia (Vietnam, Thailand and China) and the former Soviet Union (Russia, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan).

On the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), the 1990s were a time when Statoil adopted new technology created in collaboration with research institutes and development teams in the industry. Multiphase flow, subsea wells, remotely operated vehicles and floating production units made it possible to bring discoveries in deeper water and further north on stream.

Åsgard in the Norwegian Sea was the veritable diamond, with a reservoir large enough to justify investing in gas pipelines, three floating production units and a seabed infrastructure where more than 50 subsea wells were tied in. This was a pioneering project in technological terms and, like many similar ventures, experienced such substantial cost overruns that Norvik ultimately had to resign. Before his departure, however, he laid the basis for a partial privatisation and listing of the company.

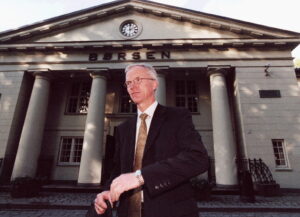

On the stock exchange

The partnership with BP ended when the latter merged with Amoco, leaving Statoil to stand on its own two feet internationally. In order to secure a freer position, new CEO Fjell wanted a stock market listing. That would leave the executive management responsible to the board rather than the Storting to the extent it had been before.

After a political assessment and debate, the Storting approved a listing, but rejected a call for the company to receive large parts of the SDFI. On 18 June 2001, top Statoil executives could ring the bell to open trading on the New York Stock Exchange and celebrate a separate listing on the Oslo Stock Exchange. The company thereby became partly privatised, with the Norwegian state as the majority shareholder.

But the international commitment had its pitfalls. Fjell failed to take the danger signals posed by a consultancy fee paid in Iran seriously enough, which ultimately cost him his job.

Merger and expansion drive

Talented businessman Lund hailed from Kjell Inge Røkke’s Aker industrial system, and was headhunted to take over the CEO role in 2004. Several major international companies had been through merger processes around 2000, and Lund wanted to strengthen Statoil in a similar manner in order to compete successfully in the global arena. He initiated face-to-face talks with Norsk Hydro CEO Eivind Reiten on a merger between his company and Hydro’s oil and energy division. This was not the first time soundings had taken place on such a plan, but Lund’s initiative succeeded because it had sufficient political support and remained secret until everything was in place.

The merger was completed in October 2007, when the company also changed its name to StatoilHydro. It reverted to Statoil ASA on 2 November 2009.

With a substantial international portfolio already in place, the merged company made an even stronger commitment to exploration in a number of new countries. An entry into land-based petroleum production in Canada and the USA proved a costly experience for the company, particularly after oil and gas prices fell from 2014. Lund stepped down in the same year.

An important task for his internally-recruited successor, the sober and reliable Sætre, was to adapt operations to the a lower level of prices both internationally and on the NCS. Under his guidance, Statoil gradually reduced its land-based activities in North America.

Climate issue and renewable energy

One challenge which had became increasingly prominent was climate change. Sætre wanted to highlight a shift of course, and did this by altering the company’s name from Statoil to Equinor. The “Stat” prefix had become less appropriate after the partial privatisation in 2001, and the company no longer wanted to be solely identified with “oil”. Its new designation was intended to reflect such values as justice, equality and balance while also signalling its Norwegian roots.

Engineer Opedal, who hails from the industrial town of Sauda north-east of Stavanger, has been at the wheel since November 2020. He has followed up the approach of being an active contributor to the green shift. His ambition on taking over was that Equinor would be climate neutral by 2050. One course being taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is to supply installations on the NCS with electricity direct from land. Others involve developing wind power, carbon capture and storage, and possibly hydrogen production.

At the same time, the company’s traditional and dominant oil and gas activities have acquired renewed relevance for stabilising the transition to renewable energy sources in a crisis-hit Europe. From that perspective, Equinor stands between industry tradition and energy transition, albeit in a more complex way than many had envisaged a short time ago.

arrow_backEquinor’s company history in brief