Statoil’s Mongstad story

It is difficult to say exactly when the story of Mongstad begins. Purely chronologically, of course, the plant has a starting point. That was when Norway’s Norsk Hydro and then British Petroleum (BP) built a refinery at Mongstad north of Bergen in the 1970s, although the plans had existed long before that. Statoil subsequently secured a stake in Mongstad in 1976 and became increasingly influential until Hydro sold out in 1987. BP had disappeared long before.

But this is not the story about Mongstad I want to relate here, and which used to be repeated again and again at “family gatherings”. It merely represents the run-up to all the drama in the 1980s – when the politicians supported refinery expansion with varying degrees of enthusiasm, when Hydro had enough, when Statoil failed to call a halt, and when everyone got a shock – or more or less in that vein.

This is story of how a refinery could run horrifyingly over budget and how some became angry while muttering more or less loudly: “What did we say?”. Its subject is not what happened. Instead, I will seek to identify why this narrative has found a place in virtually all histories of Statoil as the slightly embarrassing anecdote which always gets dragged out at family parties – even if everyone has heard it before. This is a tale about politics, industrial rivalry, good sense and gut feelings, empire-building or not, the “Mongstad symptom” and whether admitting error is shameful. But, perhaps most importantly, it is a good story.

A dramatic account

While fixing the Mongstad tale in time can be difficult, it has a clear start and even clearer end in thematic terms and begins with plans to expand a refinery. The narrative continues with a fight for the right to implement the plan, and with a project execution which progresses while becoming more and more expensive. The conclusion is the resignation of Statoil CEO Arve Johnsen and the board, and a change of direction in the company’s history. Nobody writes anything about how the Mongstad refinery managed financially after the expansion had been completed and production was under way.

In addition to a beginning, a main section and an ending, the tale also involves well-defined characters – Statoil and Hydro, Johnsen and various Hydro executives, politicians on both right and left, and the state as parent. And in the background lurk the Statoil directors, initially in bit parts and then in roles which turn the drama around.

Because a drama this was. It had everything – intrigues, accusations of empire-building, and a state within the state. As spectators, we can choose who to support – the bold, slightly irresponsible Statoil, driven to an extent by gut feelings, or sober and (far too) sensible Hydro? These two resemble children competing for parental favour, for backing from right and left at the political level. Each parent has their favourite son, but external forces – by all means call them the voters – decide which of the siblings receive the greatest benefits.

Another important factor is that this drama was not cheap. It actually cost at least three times as much as the original budget.

The Mongstad narrative contains elements which appeal to the storyteller in people, but which are also sufficiently complex for something worth studying being always findable. Perhaps the most interesting feature of the tale is nevertheless that it can be positioned in a broader context and become a Statoil history.

Two tales, two histories

“Great prestige attached to the Mongstad project,” historian Gunnar Nerheim has observed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk oljehistorie, Leseselskapet: 249. That is undoubtedly correct. Statoil had big ambitions for the refinery, related in many ways to its aim of becoming an integrated oil company – one which not only explored for and produced oil, but also refined it and sold the resulting products. Johnsen and others had devoted much time to convincing the politicians that the time was now right to expand the Mongstad facility. This may also have reflected an unconscious desire to demonstrate that Statoil had become so mature that it could manage to execute such a large and demanding project.

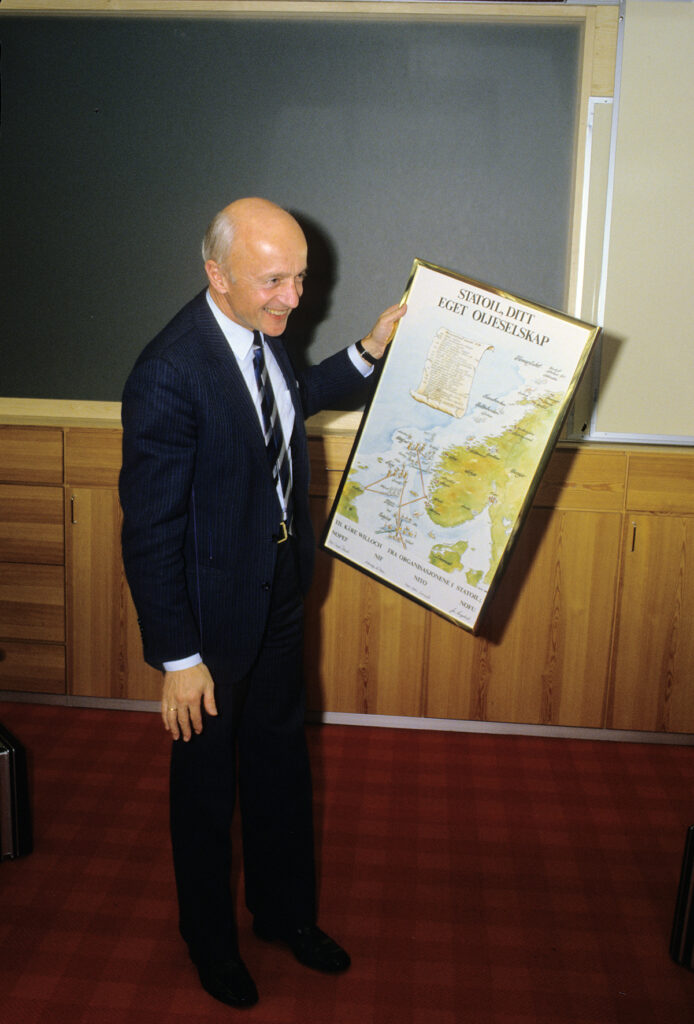

Johnsen did not need to convince the Labour Party that this was a good idea. It had faith in Statoil. The centrist parties were more difficult to bring on board, but the concept was eventually accepted by Kåre Kristiansen – the centrist Christian Democrat who was minister for petroleum and energy in the non-socialist government. The Conservatives surrendered – very unwillingly, according to Kåre Willoch, their leader and prime minister. He claimed to have yielded to avoid a dispute which could sink the coalition.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Willoch, Kåre, 1990, Minner og meninger 3: Statsminister, Schibsted, Oslo: 304.

By the time the gigantic budget overrun had been run up, Willoch was no longer prime minister. But he may nevertheless have been among those who did not exactly make it easier for Johnsen to admit that things had gone wrong.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 249. His position was perhaps a little like a youngster who has promised their parents to tackle a difficult job but must nevertheless phone home to ask for more money.

It is tempting to do a little embroidery with a story like this, to work on owning it. Both Johnsen and Willoch have written their own versions of what happened at Mongstad. And both have been accomplished gilders of their own reputations.

Johnsen has talked about inaccurate drawings, prices which were suddenly much higher than they had been, and bad timing – but never that the idea itself was bad. Statoil had become 15, he has commented. It could manage without him.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Arve Johnsen, https://tv.nrk.no/serie/mitt-liv/sesong/2/episode/3, 9 April 2021. The company might no longer have been a child, but perhaps it still possessed youthful boldness?

Willoch went further in his memoirs. He made it clear that, boldness or not, neither Mongstad nor Statoil was a good idea. This is what happens when the state runs a company. The former prime minister wrote this in 1990, and was outspoken in the chapter on Mongstad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aven, Håvard Brede, 2014, Høgres syn på statleg eigarskap i norsk oljeverksemd 1970–1984, University of Oslo: 17. He ought perhaps to have waited a few years before penning this story. Writing down narratives when they are fresh in one’s memory has advantages, but it could perhaps also be sensible to acquire some perspective on events so close at hand.

Historian Eivind Thomassen believes a lack of distance is one of the key reasons why so many versions of the Mongstad narrative exist. Many books about Norway’s oil history and Statoil were written in the 1990s, he notes, soon after the Mongstad affair had roared through the media. That was a time when covering the scandal was felt to be essential.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thomassen, Eivind, 2020, The Crude Means to Mastery. Norwegian National Oil Company Statoil (Equinor) and the Norwegian State 1972-2001: 162.

Those who have written about Norwegian oil later have perhaps read these earlier accounts and found the Mongstad narrative to be still important. Perhaps it is not Mongstad’s fault that big sums of money are associated with its name, but that it constantly has bad timing?

The Mongstad “symptom”

A search for “Mongstad” in the National Library of Norway’s catalogue throws up roughly 5 000 hits for books and almost 100 000 newspaper references. This is our fifth article about Mongstad and we have still not reached what former premier Jens Stoltenberg called Norway’s “moon landing”, which also related to the facility.

I largely agree with Thomassen’s view that the reason for so many Mongstad tales is that many of the Statoil/oil histories were written soon after the scandal. Nor has Mongstad’s reputation been helped by the fact that both Johnsen and Willoch have written about their experiences in detail.

However, I do not believe this is the whole story. To explain why historians and others have kept returning to the Mongstad affair, I think it is important to acknowledge that this is good story which also offers constant opportunities for finding new depths and nuances.

At least as important, in my view, is the fact that the tale says a great deal about Statoil – or has, in any event, been used for that purpose. Johnsen wanted, with Mongstad, to establish an integrated oil company. The Conservatives, with Willoch in the lead, wanted to identify Mongstad as a “symptom” of what was wrong with Statoil. The refinery became a symbol for the company’s development and its darker side, a symbol and a symptom of challenges in Statoil, in the relationship between it and Hydro, and in the relationship between the company and the politicians on both left and right.

This Mongstad narrative can be read as a Statoil history in miniature. I also believe that many have recounted it precisely to ensure that their version remained standing, their Statoil history became known – because, after all, we all want to own the history which defines us.