Sleipner A GBS – lost and replaced

The platform support unit had been almost wholly submerged for its final pressure tests when a loud bang was heard from within by those on board and alongside at 05.49. Two smaller bangs followed. It was quickly established that a substantial leak had occurred. The control room recorded almost 1 000 tonnes of water flowing into the drilling shaft. Although the ballast pumps were started immediately, the volume flooding in was much greater than they were designed to handle. About 18 minutes later, the Sleipner A GBS went to the bottom. That was enough time to evacuate all the 22 people who had been on board without injury. On its way down, the concrete structure collapsed completely and all the air in its storage cells was forced out – creating a tsunami effect so great that two nearby tugs lost sight of each other. The whole mass hit the seabed with great force just under 200 metres down. Seismic shock waves were registered by several seismological stations around the time of the sinking.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://draugen.industriminne.no/en/2018/05/14/the-sleipner-sinking-and-draugen/

A subsequent survey showed that the GBS was completely smashed and had probably imploded on the way down. Remains were spread over a wide area in water depths ranging from 170 to 220 metres.

Unexpected descent

Sleipner A was the first – and smaller – of two large platforms (the other was Troll A) scheduled to deliver gas under a big sales contract signed in 1986 with European buyers. The job of building the GBS was awarded to Norwegian Contractors (NC) in June 1988. Work began the following spring on what was described as “a relatively straightforward structure with several challenging production solutions”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind, 1993, På dypt vann: Norwegian Contractors 1973-1993, Norwegian Contractors, Oslo.

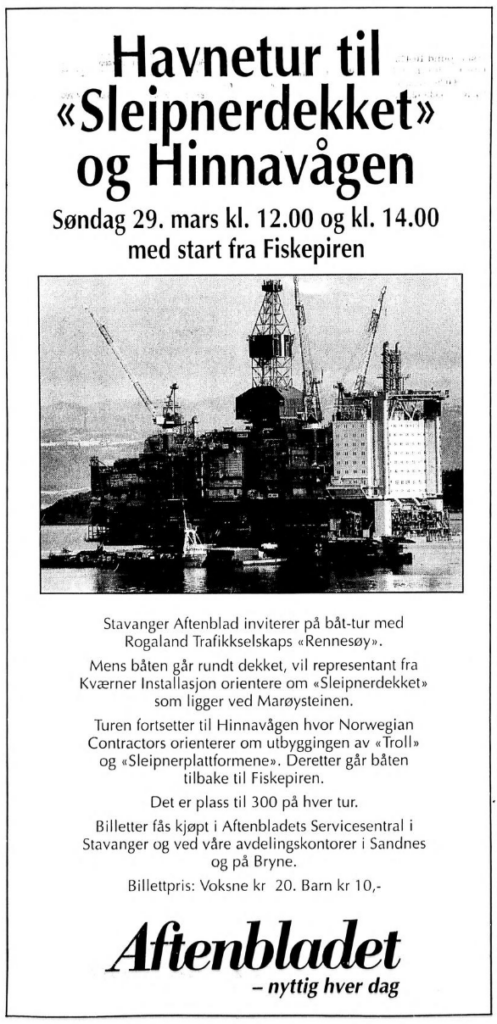

Activity at and off the Hinnavågen GBS construction site in Stavanger was in full swing during the summer of 1991. Work on Troll A had begun, Draugen was under construction, and Sleipner A was nearing completion. Casting the last of these concrete structures had finished and it lay out in the Gands Fjord to be prepared for mating with the steel topsides. The latter were also ready and waiting nearby to be joined to the GBS, with subsequent assembly hook-up work.

Sleipner East was scheduled to start gas deliveries on 1 October 1993 – but the sinking put the whole schedule under threat. Dag Halstensen, who was NC’s operations manager on the Sleipner A GBS, recalled the fateful events in the local press:

We had reached the critical trial deballasting of the GBS when it happened. We were checking that the concrete shafts and pumps functioned as they should. First came a loud bang, and then a leak which simply increased in scope. The computer monitor showed water surging into the one shaft, and it all went quickly.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 23 August 2011. It was clear that nothing could be saved from the seabed, where what remained was largely lumps of concrete along with twisted reinforcement bars and piping. The wreck had a price tag of around NOK 1.8 billion.

Complex solution

Statoil CEO Harald Norvik was preparing for breakfast with the visiting head of BP when he was called about the sinking. “Has anyone died?” was his first question, and he got the answer he hoped for. “Good, then we’ll have no problem coping with this”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Harald Norvik, personal communication, 2022.

As early as the same morning, plans were being laid for how the agreed gas deliveries to continental Europe were to be met, reports Helge Hatlestad, then Statoil’s field development head for the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, Femti år med oljeproduksjon : min historie (2021). The original scheme was scraped. This had required the A platform getting out to Sleipner East early in order to drill and complete platform wells and to provide time for commissioning and testing the Zeepipe gas pipeline to Zeebrugge in Belgium.

Instead, a multi-component solution was adopted:

- identify the fault quickly and build a new GBS tailored to the completed topside, with the mated platform reaching the field no earlier than the summer of 1993

- “parking” the topsides at Marøysteinen island off Stavanger to complete installation and hook-up of modules, followed by mating when the GBS was ready

- drilling subsea wells in dedicated seabed templates on Sleipner East and the Loke satellite, which could then be tied back to Sleipner A when it was finally in place

- move the riser function for Zeepipe (originally in a Sleipner A shaft) to a separate platform named Sleipner R and built at Aker Verdal

- secure replacement gas from other fields.

Nine hours after the sinking, Terje Vareberg, Statoil’s gas chief, could tell a press conference that the goal was to start gas deliveries on the original date of 1 October 1993.

“In many ways, the nation’s credibility as a gas supplier was at stake,” Vareberg said later. “What would they [the buyers] have done without gas? It would have been like a sudden power cut.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 23 August 2011.

Investigations by both NC and Statoil, as well as subsequent tests, indicated that the sinking was caused by a fracture in the concrete wall between the drilling shaft and an internal (three-sided) tricell. That in turn reflected underdimensioning. One consequence of these findings was that additional safety margins were adopted, with a much larger amount of reinforcement steel used in the new GBS. To meet the contractual deadline, work had to get going fast. So Statoil and NC jointly decided to build the new GBS in 19 months, with towout scheduled to start at 18.00 on 7 June 1993.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 18 August 2001. Although a formal contract between the two was not signed until December 1991, construction began quickly.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind, op.cit.

Parking space required

One question was where the topside structure should now be parked for module assembly and hook-up until it could be positioned on the new GBS. The lifting job was to be performed by an Italian crane barge, but the draught of this vessel meant the topsides could not remain at Stavanger’s Rosenberg Verft yard. Instead, Marøysteinen on the sailing channel into the Gands Fjord was selected as a suitable location for the structure, which measured 120 metres long and 35 metres wide. Local authority approval was obtained at record speed, despite grumbles from birdlovers and local fish farmers, and work could begin on blasting away bedrock and making a temporary foundation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 28 September 1991.

The topsides arrived at Marøysteinen in late January 1992, and installing 26 345 tonnes of modules could begin. Involving units for drilling, quarters, gas processing and the derrick, these were lifted into place by the crane barge and hooked up. Since it was now necessary to wait for the GBS, more time became available for equipment testing, and drilling was even conducted – but without finding oil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 29 April 1993.

Rebuilding, start-up and sequel

Version two of the Sleipner A GBS was completed in the summer of 1993 after what must be characterised as an incredible mobilisation by both Statoil and NC. “Building a new Sleipner GBS will be a test of our manhood,” observed new CEO Jan Moksnes at NC in 1992, and the company had 700-800 personnel working day and night on the job.

The topsides, now weighing 36 000 tonnes with the modules in place, was towed the short distance from Marøysteinen to the GBS in the Gands Fjord on 28 April 1993 and mated. Tow-out to the field began on 7 June in accordance with plans laid almost two years earlier.

Shortly after the sinking, a jigsaw of gas supplies from various fields was put in place to ensure deliveries if Sleipner failed for begin producing on time. But this proved unnecessary. On 24 August 1993, almost exactly two years after the dramatic event in the Gands Fjord, gas production began from Sleipner East and Loke. The 1 October start-up date for deliveries was met.

The sinking unleashed insurance payments totalling NOK 2.3 billion to the Sleipner licensees. A regress claim from the insurance companies plus Esso and the Norwegian state as self-insured parties led to a compromise settlement in the autumn of 1996, whereby Aker and NC paid NOK 340 million without admitting liability. A settlement was also reached with the Sleipner licensees, who had demanded NOK 211 million in compensation because of delays. Aker ended up paying NOK 45 million, again without admitting liability.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 18 October 2001