Discovering Johan Sverdrup – the last giant?

A good answer may not exist, or be open to a long discussion. Nevertheless, or perhaps precisely therefore, a battle was fought out in the Norwegian media over which operator was responsible for discovering Johan Sverdrup. Both Lundin Norway and Statoil claimed that honour. The former credited geologist and “magician” Hans Christen Rønnevik, while the latter highlighted its Creamed Basin team of geologists.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The chronology and exploration history in this article are based on information available in the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate’s fact pages.

Johan Sverdrup was the giant discovery which most people had given up hope of making. Even the most optimistic found it hard to believe that structures on a par with Ekofisk, Statfjord and Oseberg remained to found after more than 40 years of exploration in the Norwegian North Sea.

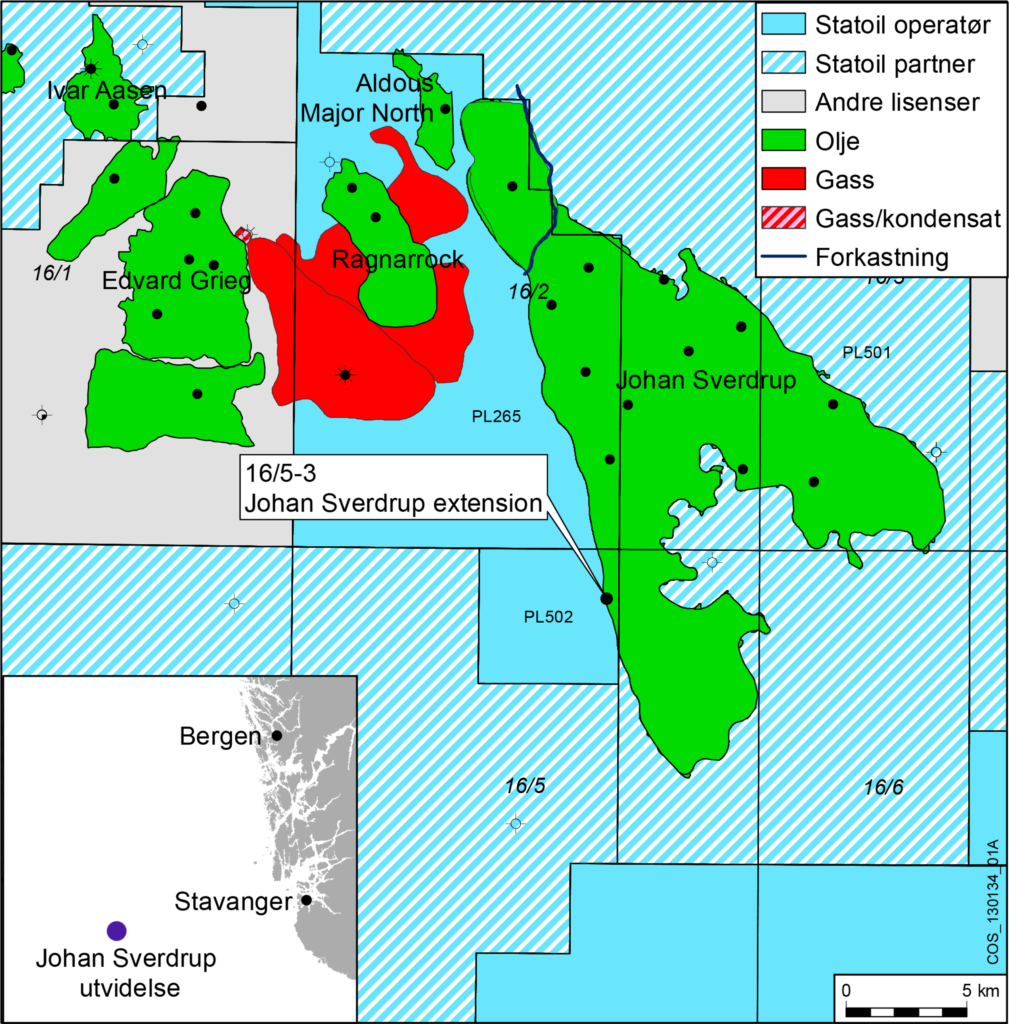

In slightly different circumstances – more precisely, being placed 600 metres further west – well 16/3-2 would have proven the field as early as 1976. But exploration results in the area had been disappointing and made drilling Jurassic prospects there look inadvisable for 32 years, until Statoil and Lundin each matured an “unlikely” prospect almost simultaneously.[REMOVE]Fotnote: A 16/3-3 well was admittedly drilled in 1989 by Esso and its partners, but aimed at a target which was both shallower and in younger rocks than the sleeping giant. It also lay well to the east of the Johan Sverdrup reservoir. The two companies named their exploration targets Aldous Major and Avaldsnes respectively.

Bringing the Utsira High alive

Production licence 265 covering blocks 16/2 and 16/3 was awarded to Statoil in a North Sea licensing round (NST 2000), with a dry well drillled as 16/2-2 in 2001. But the licensees – who included ExxonMobil and Enterprise as well as Statoil – nevertheless held onto the acreage in the hope that new opportunities might be identified. The introduction of new area fees in 2008 then made it expensive to hold onto exploration acreage, and relinquishing licences to save money became a “main activity” for Statoil. This involved returning all or part of the acreage in a licence to the state so that other companies could apply for it in later licensing rounds. By 31 December 2006, more than half the area of the original PL 265 had been relinquished. It remained the hope that the remaining area would bear fruit.

Lundin invited Statoil to participate in an application for the area which became PL 338, but was turned down. Its invitation to join when the licence had been awarded received the same response. With hindsight, that was undoubtedly the wrong decision, given that Lundin carried on and drilled its very first exploration well there. That yielded an oil discovery originally called Luno and later Edvard Grieg. This find was not only interesting in itself, but also demonstrated that opportunities existed for oil to migrate through the Utsira High area and further east into Middle and Late Jurassic reservoirs. That possibility had previously been considered uncertain. These represented precisely the formations which Statoil and Lundin were working on from their respective sides. The promising results in PL 338 prompted both companies to increase their holding in PL 265 by acquiring 10 per cent from DNO and Talisman respectively.

Statoil’s wells on its Ragnarock prospect in PL 265 were also promising. Oil was found there in a chalk formation just above the basement as well as in fractured basement rocks. Although the discovery was not considered producible, it encouraged further assessment of areas further east by confirming – like Luno – that oil could migrate in this direction.

Both Statoil and Lundin were now seeking elephants, as the oil industry calls massive discoveries.

“[Both] were hunting for oil in the same part of the Utsira High,” said Statoil exploration chief Tim Dodson.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Arnt Even Bøe, 2014, Utfordreren. Lundin Norways første ti år på norsk sokkel. “We attacked in different ways, but ended up in the same place. Lundin’s discovery of Edvard Grieg was an important piece of the jigsaw which prompted us to apply for PL 501. But so were the Ragnarock wells.”

In other words, although the two companies participated in the same PL 625 licence, they were hungry rivals. Both applied during the 2008 awards in predefined areas (APA) for the relinquished PL 265 acreage. Soundings were made about submitting a joint application, but the fear of being fobbed off with a small percentage share of an area with great potential led Lundin to pen its own request for a sole licence and the operatorship.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The upshot was that both companies secured 40 per cent holdings in the new PL 501, with Lundin as operator and with the remaining 20 per cent awarded to Denmark’s Maersk. From the government’s perspective, it was natural for Lundin to be given the operatorship since Statoil had not been much of a driving force when it operated the area. In addition, the Swedish company could be said to have the honour of reviving exploration interest there.

Several discoveries become one

Transocean Winner spudded (started) the first exploration well on PL 501 in July 2010. The prospect being drilled was named Avaldsnes after Norway’s first royal seat, and because it was on the eastern side of the Utsira High – in the same way that Avaldsnes lies on the east coast of Karmøy island north of Stavanger. Early on 6 August, pulling out the bit confirmed the discovery of oil in a good reservoir. All the signs were that this was a big find, but just how large remained unclear. Production testing confirmed that the biggest optimists had been right, and that more wells would be needed to delineate the discovery.

Almost exactly a year later, Statoil spudded a well on Aldous Major in PL 265. This also proved oil in an extremely good reservoir, and the first official reserve estimates put it in the same league as Avaldsnes – 30-65 million standard cubic metres (188-406 million barrels) of recoverable oil with a potential for further resources nearby.

That sparked a public dispute over who could claim responsibility for proving the area and which discovery was the biggest. This was best exemplified by the front pages of business daily Dagens Næringsliv and local daily Stavanger Aftenblad on 17 August 2010, which presented Statoil’s Sigrid Borthen Toven and Lundin’s Hans Christen Rønnevik respectively as the hero of the hour. Statoil’s communications head was undoubtedly closer to the truth when he talked to Stavanger daily Rogalands Avis the following day:

Positioning the … bit in the right place follows a lot of work on analysing data over a long period. As is so often the case in business, the large organisations seek to claim the honour when oil companies make big discoveries such as Aldous Major South.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis, 18 August 2010.

A hectic period followed with drilling of appraisal wells and the publication of new figures. Disagreement also prevailed between Statoil and Lundin over how many of these wells should be drilled, and where and when that should happen. When two captains are in charge of separate ships, they undoubtedly fail to steer the same course all the time.

During appraisal drilling, it often happens that new discoveries get bigger. Towards the end of 2010, Statoil estimated that Aldous Major and Avaldsnes – which are actually a single field now called Johan Sverdrup – contained 1.7-3.3 billion barrels of recoverable oil. In mid-2022, the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) put the overall recoverable reserves at 2.7 billion barrels of oil equivalent – making it the sixth largest field on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/facts/field/johan-sverdrup/, accessed 28 February 2022.

Unitisation

Once it became clear that the two discoveries were in communication, it was first renamed Johan Sverdrup – after the 19th century “father of Norwegian parliamentary government” – and then unitised for development as a single structure. This meant that the licences were merged into one unit with the licensees holding proportionate interests. Although Lundin wanted to become the operator, this role was awarded to Statoil – not least because it held by far the largest share of the discovery as a whole.

Looking back, both companies can pat themselves and each other on the back for ability and luck, while other players can shed bitter tears over farming out of licences too early. Johan Sverdrup came on stream in the autumn of 2019 and will rank as the highest oil producer on the NCS for years to come.

arrow_backUp and down with US shaleIntermezzo in Mesopotamiaarrow_forward