From Statoil to Circle K

“We have more forecourts than Starbucks has coffee bars,” Jacob Schram, Europe head of what was called at the time Statoil Fuel & Retail (SFR), proclaimed in January 2016. “We have 15 000[REMOVE]Fotnote: These figures included service stations in Canada, the USA, Mexico, Japan, China, Indonesia and Guam as well as Europe. outlets, it has 10 000. Our turnover is USD 15 billion, which is twice the Starbucks figure.” He was addressing 3 000 employees who had assembled at the Telenor Arena venue outside Oslo to launch a new name for the service station chain which had borne the Statoil label for more than 20 years in Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://e24.no/privatoekonomi/i/4daAMa/bensin-statoil-doepes-om-til-circle-k, accessed 12 January 2022.

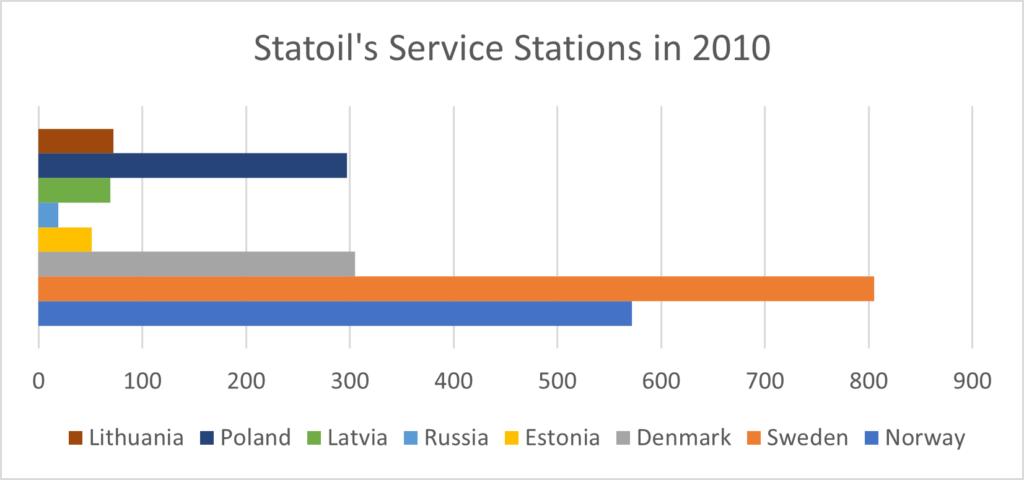

Until 2010, Statoil had retail satellites in Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Russia. Its service station subsidiaries in Norway, Sweden and Denmark had been operated since 1996 as a single company, a kind of “Statoil Scandinavia”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1996, Statoil: 28. The common denominator for them all was that they marketed and distributed oil products – particularly petrol and diesel oil. This business was primarily conducted through the many forecourts as well as bulk sales of maritime and aviation fuels. All the subsidiaries were merged in 2010 into SFR, which then secured a stock exchange listing.

Why was this company established and listed? And why did Statoil pull out of the service station sector completely in 2012?

No longer part of the core

“The energy and retail business has different drivers for value creation compared to [our] core business,” Statoil noted on its website when announcing the sale to Canada’s Alimentation Couche-Tard. That was why SFR was established and listed [REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/no/news/archive/2012/04/18/18April12StatoilAcceptsBid.html, accessed 16 March 2022.

Statoil’s ability to make money from oil and gas production involved different factors than those which governed retailing petroleum products. CEO Helge Lund believed it was better for the two companies to function separately, without explaining why.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Børsnoterer bensinstasjoner” (Jakob Schultz), 3 September 2010, National Library of Norway. But it is reasonable to assume that financial considerations and changing views of the core Statoil business played a part.

Explanations differed when Statoil sold its German and Irish marketing subsidiaries in 1997 and 2006 respectively. The company made insufficient money in Germany and further expansion was too difficult. But the business in Ireland was doing well, and the grounds for selling out were said to be strategic in character. In both cases, Statoil maintained that it wanted to use its expertise and financial resources elsewhere – the Baltic states, Poland and Scandinavia. These countries can be said to have been Statoil’s core area for retail.

Being in a “core area” was little help in 2012, when the parent company no longer viewed the sale of oil products as part of its “core business”.

It then used words such as a “milestone in Statoil’s strategic development”, and referred to a desire to free up capital, streamline its own portfolio and concentrate even more strongly on being a “technology focused upstream energy company”. In other words, Statoil wanted to focus its attention on oil production and let others deal with selling oil products at the retail level.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/no/news/archive/2012/04/18/18April12StatoilAcceptsBid.html, accessed 16 March 2022.

During the 1970s, Statoil’s goals included becoming a fully integrated oil company involved in every aspect from exploration to selling petrol and diesel oil directly to consumers. It had been committed to this objective in subsequent decades in Norway, Scandinavia and other European countries, building up new subsidiaries and forecourts as well as taking over such outlets from others.

SFR continued to make changes and pursue this commitment after its 2010 listing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Planlegger gigantsalg” (Jakob Schultz), 9 February 2011, National Library of Norway. Although the company’s share fluctuated in price, it performed by and large well and was regarded as a good investment. Profits were up from 2011 when the sale to Alimentation Couche-Tard occurred.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, ”Schibsted er favoritten” (Andreas Nyheim), 2 January 2012; ”Selger gigant, kjøper smått” (Andreas Nyheim), 21 February 2012; “Bensinsalg ga milliardgevinst” (Anita Hoemsnes), 27 July 2012, National Library of Norway.

Statoil nevertheless opted to sell its shares in SFR, and all the minority shareholders eventually followed suit. Leif Sande, president of the Norwegian Union of Industry and Energy Workers, was critical of the sale. He supported the idea of a fully integrated oil company and believed that this gave Statoil a broader foundation. In his view, that provided greater stability and flexibility and thereby more security for the employees.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Svært skuffet” (Arne Grande), 19 April 2012, National Library of Norway.

But the company management did not agree. Rather than broadening its base, they wanted to concentrate the business. SFR was sold in 2012 for NOK 16 billion, with NOK 8.6 billion going to Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Avtale setter stopper for budkamp” (Morten Bertelsen, Espen Linderud and Kjetil Sæter), 19 April 2012; “Bensinsalg ga milliardgevinst” (Anita Hoemsnes), 27 July 2012, National Library of Norway. That yielded a post-tax sum of NOK 5.8 billion which, according to CFO Torgrim Reiten, was to be invested in oil production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Avtale setter stopper for budkamp”, op.cit.

Name change

In 2016, then, 3 000 people who had so far sold petrol and hot dogs under the Statoil logo were assembled near Oslo to learn about a change of name to Circle K. This designation, which already covered the 10 000 or so other forecourts owned by Alimentation Couche-Tard, was now extended to the former SFR stations.

The Canadian owner would not reveal what this change of name would cost, but that was not much of a consideration. In any event, it could not continue to use the Statoil name after 30 September 2019.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://e24.no/privatoekonomi/i/4daAMa/bensin-statoil-doepes-om-til-circle-k, accessed 12 January 2022.

Statoil’s service stations were a thing of the past, and the company’s history had thereby also changed.

arrow_backOil and the environment in AustraliaExploration in New Zealandarrow_forward