Service stations in east and west

It was important for Statoil from its early years to achieve maximum integration as an oil company, covering the whole industry spectrum from exploration and production to refining and distribution. Arve Johnsen, Statoil’s first CEO, was especially concerned with this. So were many politicians, particularly in the Labour Party.

Integration would give the company control over its whole value chain and allow it to take out profits in those areas where these could be made at any given time. That was viewed as important in a fluctuating market, and was the prevailing theory in the petroleum sector until the early 2000s.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Njål Gjedrem, Statoil’s Russia manager in the 1990s, in correspondence with Julia Stangeland in April 2022.

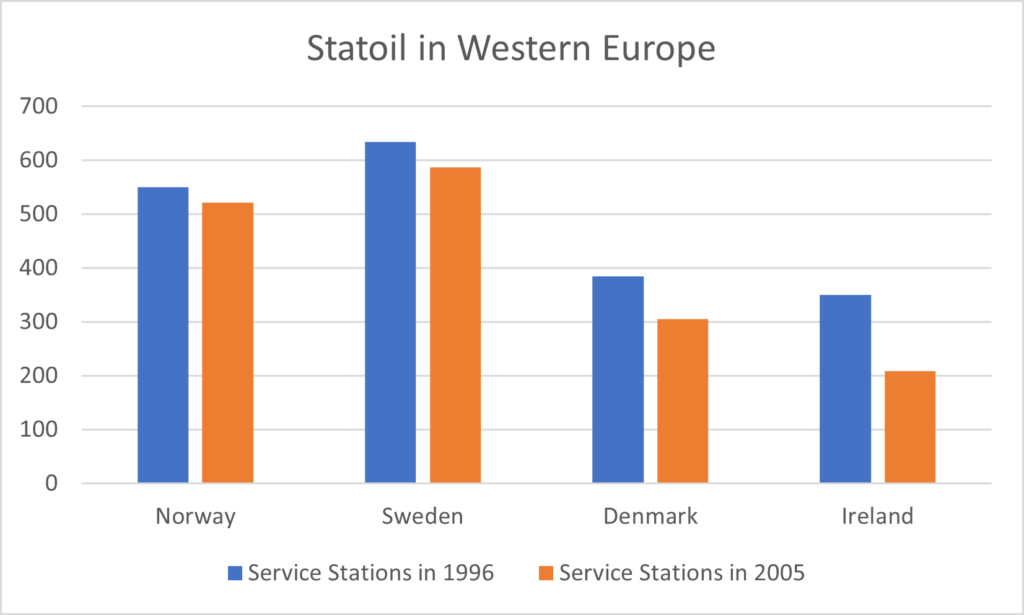

During the 1980s, Statoil took steps to become a Scandinavian marketer of diesel oil and petrol. It initially secured gradual control of Norway’s Norol service stations, and also acquired Exxon’s forecourts in Sweden and Denmark. These three subsidiaries were needed to ensure sales of refined oil products, and the company also aimed to rank among the biggest oil distributors in the Scandinavian region. But Statoil had an even more ambitious goal. Like the ancient Vikings, it travelled both east and west – but fortunately in a far less brutal fashion.

From scratch – organic growth

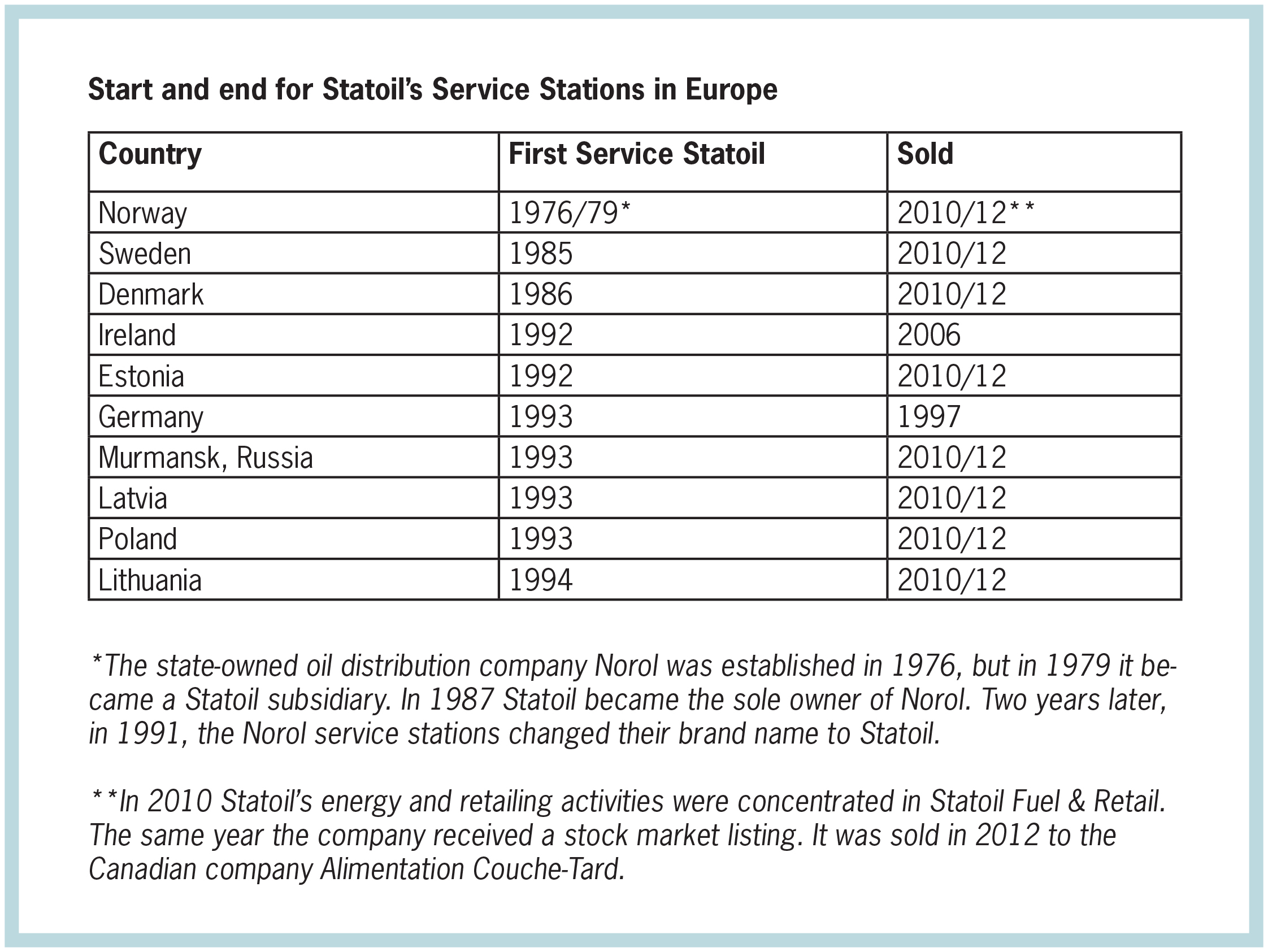

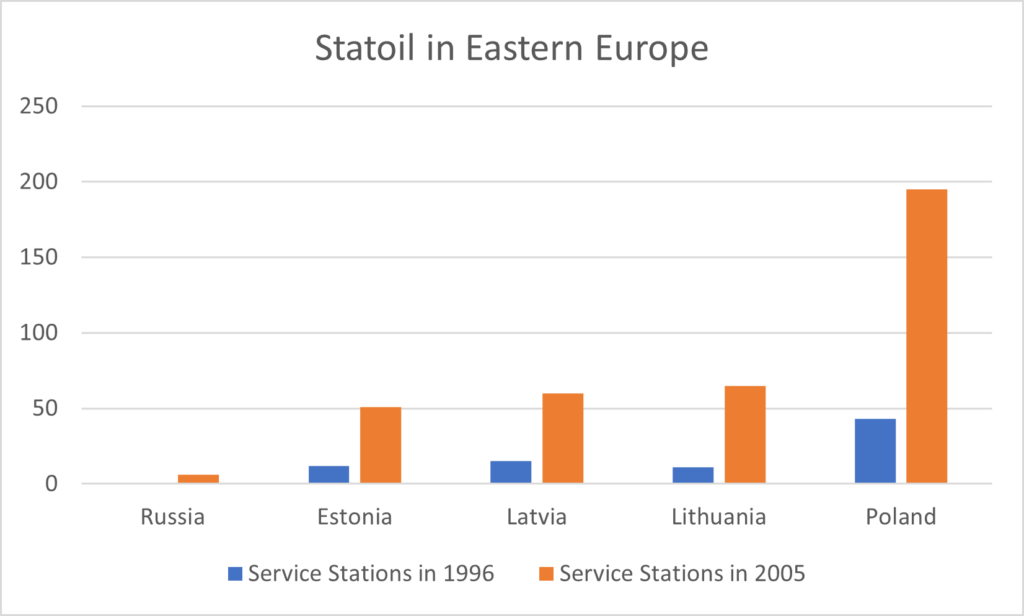

During the 1980s, Statoil built up service station networks in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and the former East Germany. The number of its forecourts varied from country to country, both initially and in subsequent years.

A common denominator for its involvement in these six nations was that – unlike the approach taken in Scandinavia – the company did not acquire established retailing networks. Its service stations were established from scratch. Historians such as Marten Boon call this process “organic growth”. It requires more time and resources than the alternative path to expansion through the acquisition of other companies.

The key question is why Statoil took the organic route in eastern Europe rather than acquiring existing service stations.

According to the board minutes of 18-19 June 1992, it was “hardly possible to acquire stations in relevant locations from other companies”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Statoil, 18-19 June 1992. The meeting was concerned with the former East Germany, but might equally well have been talking about Poland, Russia or the Baltic states.

The minutes are terse and do not go into detail about why such purchases were not relevant. But the probable reason is that retail markets in these former Eastern Bloc countries were less developed than in Scandinavia. Few forecourts existed to be acquired, and those there were would not sell. On the other hand, space existed in the market for establishing new companies.

During the 1990s and the first decade after 2000, new service stations were steadily opened in the Baltic states, Poland and Russia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1996, Statoil: 29; Annual report, 2005, Statoil: 27. But the German subsidiary with its 50 outlets was sold as early as 1997 because it was not making enough money and growing the operation was proving difficult. Statoil preferred to divert the resources to Poland and the Baltic states instead.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1997, Statoil: 11 and 26; Minutes, board meeting, 17 March 1997.

While it opted to build up from scratch with various “ingredients” to the east, the company chose a quicker solution in the west.

Ready-made – inorganic growth

Statoil reached agreement in 1991 – the same year it established itself in Estonia – to acquire BP’s retail arm in Ireland. These service stations were taken over the following March.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1991, Statoil: 30.

This “ready-made” Irish company grew during the 1990s both in the form of more forecourts and through increased market share. It continued to expand through acquisitions.

In 1995, Statoil Ireland purchased Conoco’s 257 service stations in Ireland and thereby doubled its market share from 10 to 20 per cent. That gave it a leading position in the Irish service station sector.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1995, Statoil: 26; Annual report, 1996, Statoil: 29; Annual report, 1997, Statoil: 26. But having many forecourts did not automatically mean growth. Some rationalisation of the network was needed. Statoil’s market share in Ireland was at least as important as the number of outlets.

From 1992 to 2006, Statoil Ireland advanced from fifth to first place among the country’s forecourt chains, with 1 100 employees and 236 stations. The company announced in the latter year that it was selling its Irish operation to Canada’s Topaz Energy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2005, Statoil: 27.

Statoil explained that the decision was purely strategic. It preferred to make a bigger commitment to Scandinavia, Poland and the Baltic states.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2006, Statoil: 27; https://e24.no/naeringsliv/i/8mGw5d/statoil-selger-bensinstasjoner ,accessed 19 July 2021. The company may have felt closer ties to the Scandinavian market, at the same time as it was more rewarding to devote time to that part of the retail network it had built up from scratch.

Concentration

Although revenues from retailing varied with oil prices and refinery margins, Statoil generally had a strong position in energy and retailing. Its 2007 annual report noted that the company remained the largest or second-largest service-station retailer in the countries where it was involved.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, Statoil: 35. In other words, the work it had put in was yielding a return.

After first having advanced on a broad front to establish service stations, the company decided that it would make sense to concentrate on what it regarded as its core region. Germany and then Ireland were accordingly removed from the portfolio.

The Irish sale can also be interpreted as the beginning of the end for Statoil as a fully integrated oil company. Four years later, in 2010, its energy and retailing activities were concentrated in Statoil Fuel & Retail. The latter company then received a stock market listing. It was sold in 2012 to another Canadian buyer – this time Alimentation Couche-Tard.