Discovering Gullfaks: Hiccups and Blowouts

When prioritising exploration areas on the NCS, Statoil CEO Arve Johnsen had set three key criteria for the choice – it had to contain oil, be large, and lie in a reasonable water depth.

Three criteria

Among the most attractive areas under consideration on the NCS during the mid-1970s were blocks 30/6, 34/7 and 34/8, which later yielded the Oseberg, Snorre and Visund fields respectively. An assessment of which prospect is best will always be subjective. But the recommendation from geologists Svein Nedland and Georg Hamar to the Statoil management was clear – blocks 34/7 and 34/10 were the finest in the Norwegian North Sea.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Statoil, 15 September 1976.

The geology admittedly looked complex, but concerns about deep water and the possibility of encountering gas in the other blocks carried more weight. Moreover, exploration chief Phil Halstead thought geological challenges could help in building a company with a strong technological backbone.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B V, 2007, 34/10. Oil the Norwegian way – a story of boldness, Statoil: 57-58.

Expectations of 34/10 were so high that it was quickly nicknamed the golden block, while the almost equally attractive 30/6 became the silver block. Statoil was named exploration operator for both, but had to choose which of them it would retain in the event of a discovery. It opted for 34/10.

All Norwegian

The golden block was awarded outside the normal licensing round system, as had been done earlier with Statfjord. It also fell outside usual practice on the NCS until then by having only domestic licensees. All 49 of the production licences previously issued had featured foreign companies as operator or partners. PL 050 was the first with no non-Norwegian participants. Statoil was operator with no less than 85 per cent (reduced to 12 per cent when the field came on stream, as a consequence of the “wing-clipping” covered in a separate article). Hydro and Saga Petroleum were partners.

Dramatic drilling

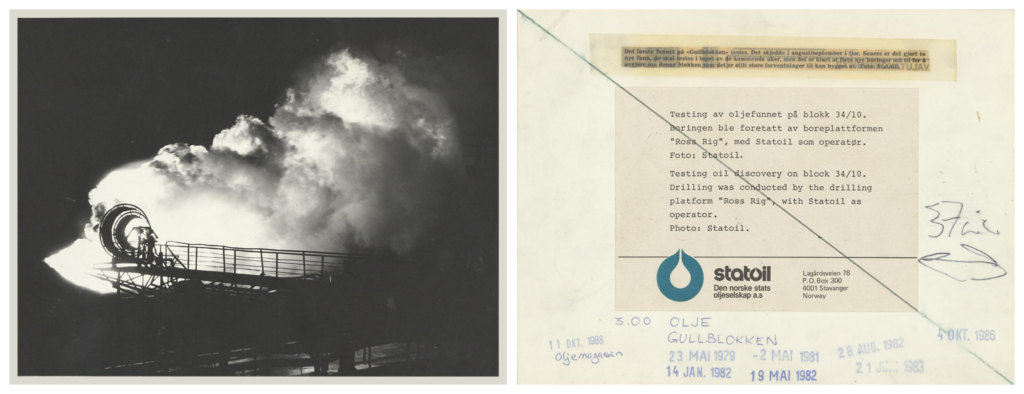

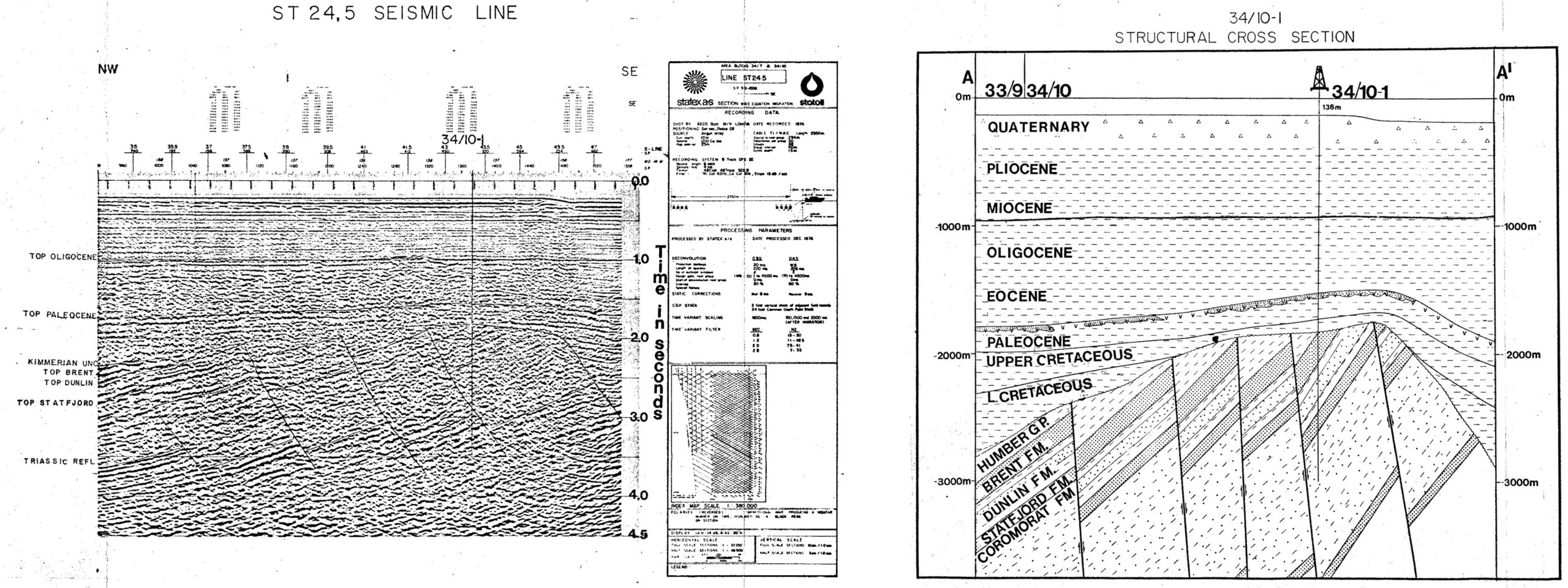

The most interesting structures in 34/10 had been designated Alpha and Delta, and a wildcat (first exploration well) was spudded on the latter just four days after the formal licence award. Detailed studies of the drilling target had already been made, including geological forecasts and predictions of pore pressure – in other words, what rocks were likely to be found at which level, and under what pressure. These assessments indicated that the oil-bearing reservoir was probably at a depth of 1 845 metres and that unusually high pressure might be encountered. But surprises were in store.

Mads Grinrød, who was drilling supervisor when Ross Rig drilled the Gullfaks wildcat, recalled:

We came on the oil suddenly. The drilling rate suddenly speeded up enormously as we moved out of shale into sandstone. When the driller pulled out the string, the oil came up with it. Before we knew what was happening, crude had filled the well right up to the drill floor and spilt onto the shale shaker. We shut in the well and got control over what could potentially have become a critical position.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B V, op.cit

People undoubtedly had a hectic time of it both on the rig and ashore. Kyrre Nese remembered: I was sitting close to Joe Kauffmann, assistant vice president for exploration and production, in Lagårdsveien 78 when 34/10 kicked. Suddenly, Joe’s office was alive with loud and intense telephone conversations. After a short while, he rushed like a madman out of the office. Joe was a cornerstone of the operations area in Statoil at that time … A blowout on Gullfaks would have had consequences for the company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kyrre Nese, 2022, Facebook pages on Equinor’s 50-year history.

Drilling superintendent Ed Diamond was handling the situation from land, and was based in Dusavik outside Stavanger. Esso, being partner in the license, were asked for some constructive input to the situation, to which the reply was: “Houston is concerned”. Ed laid eyes on the Esso representative and stated: “Houston is concerned??!!! What the hell do you think I am?”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Per Lindberg in e-mail 1. august 2022.

An uncontrolled release of oil and gas, or blowout, can lead to large quantities of petroleum escaping from the well, and pose dangers for equipment and crew. If this is not brought under control and “killed”, a relief well may need to be drilled to intercept the original borehole and thereby shut it down. Hasty plans were laid for such an intervention, but it fortunately proved unnecessary.

Within a week, the well was back under control and drilling could continue.

Complex geology and shallow gas

Work on the well progressed without much further drama, resulting in a very promising oil discovery. But suspicions of geological complexity were borne out, and an unusually large number of wells – 10 in all – were needed to understand the reservoir.

The 10th exploration well in what was to become Gullfaks became the first to strike shallow gas – located in rocks above the actual reservoir. That resulted in a proper blowout, forcing the rig to move from the location. Since the gas was shallow, modest in quantity and under limited pressure, no emissions/discharges occurred and no harm was done to people/equipment. Another rig also eventually arrived and could plug the well.

Block 34/10 was the first area of the NCS where Statoil did a three-dimensional (3D) seismic survey. The resulting 3D image of the subsurface, built up from sound waves, provided a basis for interpreting what might be present to guide appraisal drilling, estimates of oil in place and deciding on recovery.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status no 4, vol 4,. 1982: 10-11.

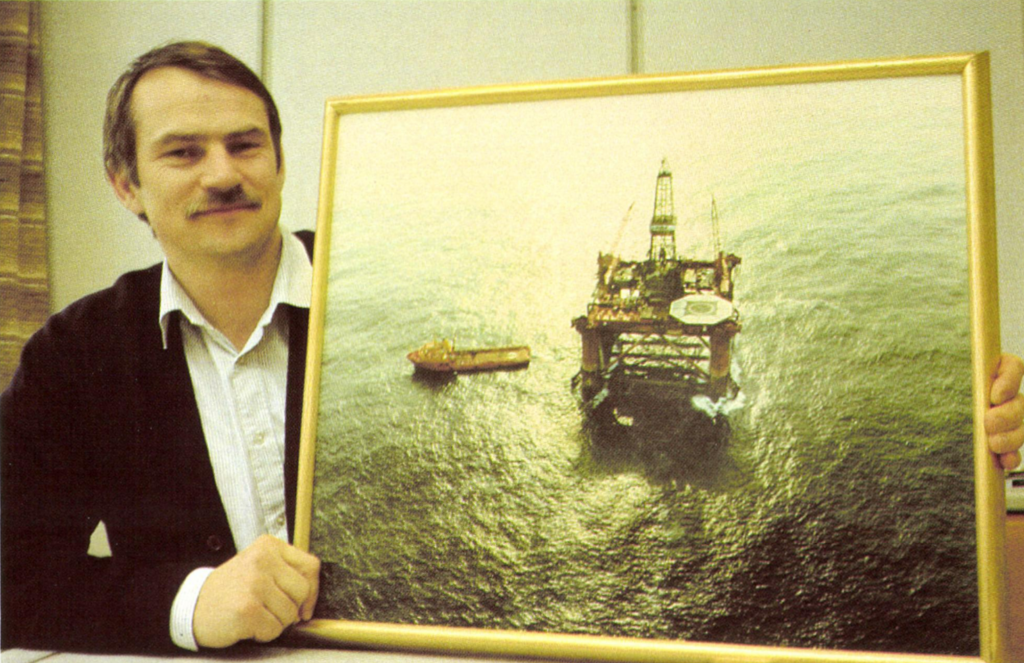

A commerciality report was produced in the autumn of 1980 for what was still known as Delta East. Corresponding to today’s plan for development and operation (PDO), this showed how the oil and gas could be recovered in a prudent and profitable manner. Statoil had already produced a similar report from its small Tommeliten discovery, but this was halted on strategic grounds before submission to the government. “Johnsen feared that people sceptical to Statoil would say ‘let them show they can manage a small development before they’re allowed to be responsible for large projects like Gullfaks’,” recalls Statoil veteran Helge Hatlestad. “As so often, Johnsen’s strategy was successful.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Helge Hatlestad, 15 April 2021, by e-mail.

A project team involving 50 full- and part-time participants was established to secure the basis for a formal declaration of commercialisation. It quickly became clear that the discovery was substantial, but geological complexity and water depths extending in some cases beyond 200 metres were major challenges.

The final report affirmed that the discovery was producible, and the original plans called for no less than four platforms. That was partly because of existing limits on how much a well could deviate from the vertical during drilling. Subsequent technological advances changed this restriction, and the Gullfaks area ended up with three platforms. The last of these became known as the heaviest construction ever moved. Statoil would be the development operator in close collaboration with Hydro and Saga and with Esso as technical assistant.

The commerciality report for Gullfaks was approved by an extraordinary general meeting of Statoil in 1980. Interestingly enough, Harald Norvik – later to become CEO of the company – represented the state as owner on that occasion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B V, op.cit: 62.

An oil price of USD 35 per barrel was assumed in the report but, by the time the field came on stream, this had slumped to USD 10. Nobody could have predicted such a price change when the first development phase was finally approved by the government on 9 October 1981.

arrow_backQuiet in the ranks on landHow Statoil landed the golden blockarrow_forward