Statfjord awarded

The Storting had resolved that the largest possible state participation through Statoil was desirable. At the same time, the industry ministry was fully aware that any development needed an experienced operator. That was particularly true for the Norwegian blocks close to Britain’s big Brent field. Giving this role to Statoil was out of the question. Production plans being pursued for Brent made it clear that mapping the Norwegian acreage was a matter of urgency, and the state oil company was not sufficiently mature for such a demanding job.

Responsibility for negotiating licence terms to cover these high-priority blocks fell to veteran civil servant Karl-Edwin Manshaus. He had worked as a legal expert in the industry ministry’s oil office on framing legislation for the petroleum sector, and also played a key role in establishing Statoil and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

Negotiations over the “Brent” blocks in 1973 lasted for several weeks, with many considerations needing to be taken into account. Manshaus wanted to get Norwegian participants into the licences and to ensure spin-offs for domestic industry. That meant Statoil should receive a big stake and have its share of exploration costs carried by the other licensees. At the same time, an experienced and well-capitalised operator was sought. But neither it not other private foreign companies could be allowed an overly dominant role.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Borchgrevink, A, 2020, Giganten: Fra Statoil til Equinor: Historien om selskapet som forandret Norge, Kagge Forlag, Oslo: 61. Manshaus was also to ensure that Statoil emerged well from the negotiations with the forthcoming operator.

Shell and Esso, respectively operator of and partner in the Brent field, were no longer relevant as operator for the Norwegian blocks, and their dream of control on both sides of the UK-Norway boundary evaporated. The threat that the two companies might rig the division of the oil between the two sectors in order to avoid Norwegian taxes was considered too great. Concern was expressed that oil could be drained from Norway’s side of the boundary to the British unless the Norwegian authorities kept a close watch.

Manshaus offered Shell and Esso 10 per cent each in the licence.

US oil company Chevron was envisaged as the operator at an early stage of the talks, and offered a 15 per cent stake. However, it was not satisfied with the terms offered by the government. The ministry’s reaction provided a clear expression of its privileged negotiating position. Rather than continuing to negotiate with Chevron, it quite simply offered the job to the next relevant candidate.

Instead of having to accept the multinational oil companies’ rules, as in earlier licensing rounds, the ministry could now in reality play them off against each other as a result of the substantially greater interest generated by Ekofisk. Those who refused to accept Norway’s terms soon found themselves excluded. Mobil ended up accepting the conditions Chevron had rejected and took on the operatorship. The requirements set for the US major included transferring knowledge and expertise to Statoil through active training.

Final negotiations with Mobil were conducted at the end of June 1973, with CEO Arve Johnsen also present on behalf of the state oil company.

In addition to the existing terms, Manshaus now presented yet another condition. Statoil was to have an option to take over the operatorship 10 years after a possible commercial discovery had been made. Once its first shock had subsided, Mobil yielded. Blocks 33/9 and 33/12 were too attractive to lose. In its innermost thoughts, too, the US company undoubtedly did not believe Statoil would be in a position to become the operator after just 10 years.

The outcome was that Statoil received 50 per cent of the licence, Mobil 15 per cent and the operatorship, and Esso, Shell and Conoco 10 per cent each. Four other companies also received small stakes[REMOVE]Fotnote: Saga Petroleum 1.875 per cent, and Texas Eastern Norwegian Inc, Amoco Norway and Amerada Hess Norway 1.0416 per cent each.

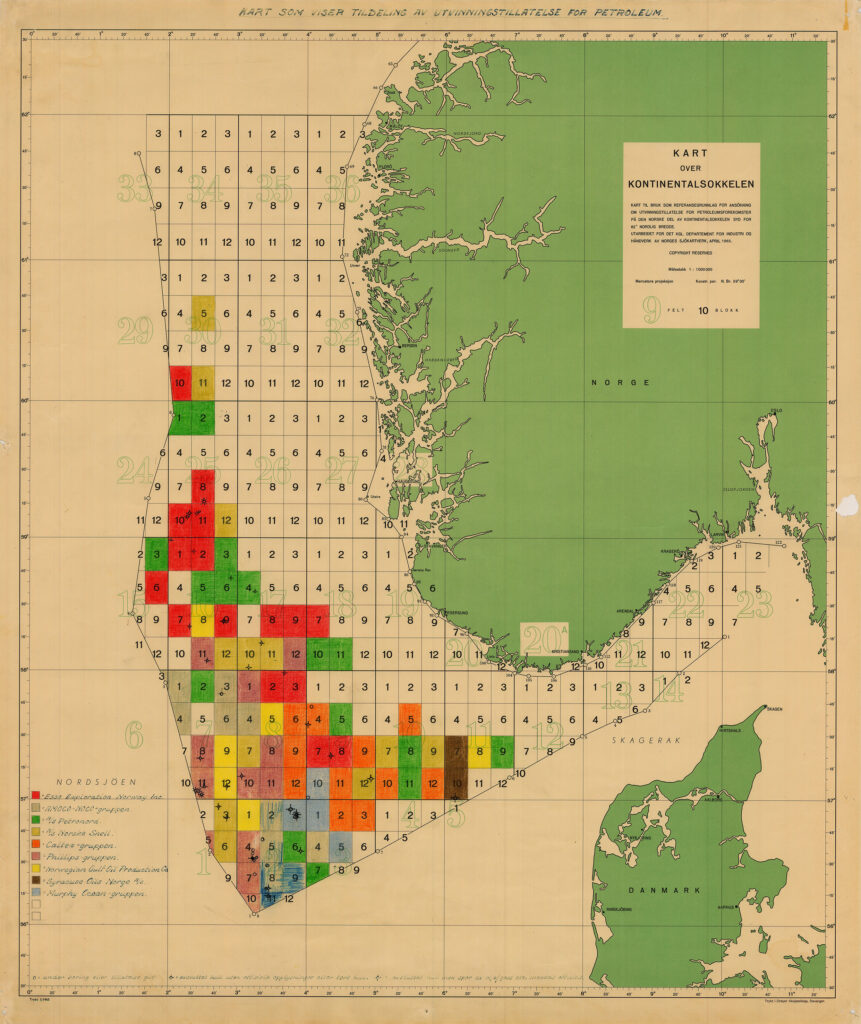

Third licensing round results

A third licensing round on the Norwegian continental shelf had been initiated in parallel with the negotiations over Norway’s “Brent” blocks. Advertised in the summer of 1973, this round extended in reality all the way until 1977. Thirty-two blocks were put on offer, while nine “key” blocks were held back in part until Statoil produced a plan on how these should best be utilised. The conditions negotiated when awarding the Statfjord acreage were established as the norm and, in many respects, represented the new rules of the game. Whether state participation was attainable through awarding interests to Statoil was no longer the question – only how large that involvement should be.

White Paper no 30 (1973-74) enlarged on the political goals of state participation. The object was said to be twofold. First, such involvement opened for additional government revenues beyond merely taxing the industry. Second, it provided an opportunity to influence licensee decisions once a licence was allocated.

In total, therefore, 12 production licences covering 20 blocks were awarded in the third round. Statoil – as it had been officially known since 1974 – received at least 50 per cent in each. Some of the licences also introduced a sliding scale which could potentially give the company a holding of up to 80 per cent.

Most of the licences also contained a provision which allowed Statoil to take over as operator after eight years, while its share of exploration costs was to be carried by the other licensees.

The pracsise giving the state company a clearly preferential status with an interest of 50 per cent or more, continued after 1973. By 1977, it was the turn of the “golden” block – 34/10. Johnsen and Statoil reached one of their absolute pinnacles there by securing a share of no less than 85 per cent and the operatorship. With this award, the company manifested its privileged position.

arrow_backArve Johnsen – a visionary pioneerCo-owner of oil pipelinearrow_forward