Troll on land

The path from exploration to discovery, appraisal, planning development and operation, constructing installations, and the actual realisation and startup of production is a lengthy one. It also takes a long time – no less than 43 years in the case of Norway’s Flyndre field – and changes often occur along the way. With a field as large and complex as Troll, a protracted journey is understandable. But changes as fundamental as those made in this project, and at such a late stage, are rarely seen.

With the discovery well completed in November 1979, Troll was declared commercial in November 1983 and the first plan for development and operation (PDO) of its first phase was submitted in September 1986. The Statoil board took a number of important decisions in the second half of that year covering the Troll and Sleipner gas fields: [REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meetings, Statoil, 11 September 1986, 20 October 1986 and 12 November 1986.

- approving the Troll gas sales agreement with European buyers

- declaring the part of Troll located in blocks 31/3, 31/5 and 31/6 (production licence 085) commercial

- Troll phase 1 to be developed

- Statoil increased its participation in that part of Troll located in PL 054 pursuant to the sliding scale provision

- Sleipner East to be developed

- Statoil increased its participation in Sleipner East pursuant to the sliding scale provision

- Statoil participated in the development of, and was operator for, the transport system to Zeebrugge in Belgium.

Plans and concepts

The PDO approved by the Statoil board was based on no less than 26 appraisal wells and their evaluation as well as a sales agreement which specified that up to 20.26 billion cubic metres of gas would be delivered annually for 29 years from 1 October 1993.

Almost NOK 1 billion is said to have been devoted to developing the deepwater technology required to produce Troll phase 1. And the overall development cost is estimated at NOK 20 billion in 1986 value.

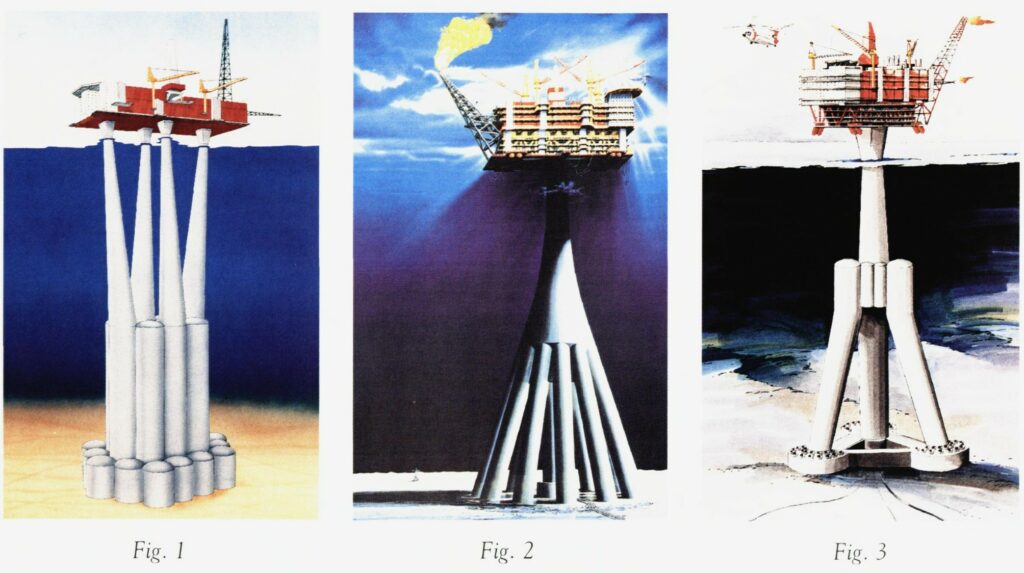

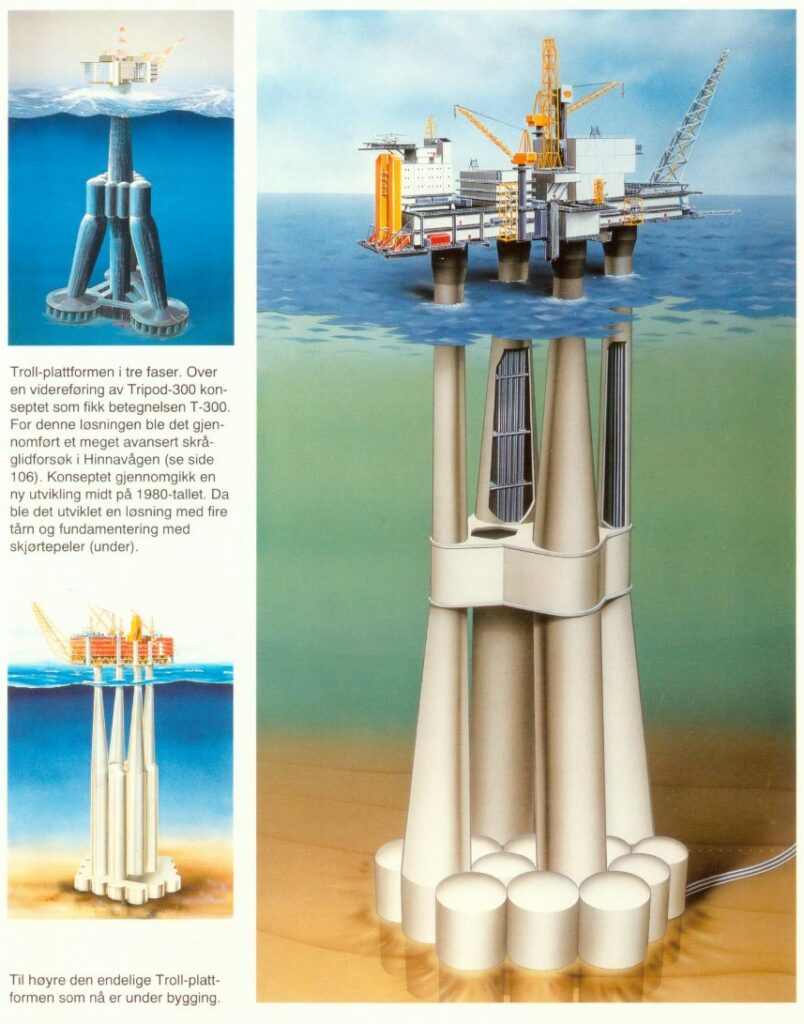

Gas was to be produced and processed on a fixed platform. Supported by a concrete gravity base structure (GBS), this would rank the world’s tallest structure ever moved. When the PDO was drawn up, several possible concepts were under consideration. But it was clear that the Condeep technology based on a concrete GBS would be utilised for an installation standing in more than 300 metres of water and supporting 62 000 tonnes of topside weight.

One of the Condeep concepts, known as the Tripod, called for inclined shafts of varying thickness in the GBS. Widespread doubts were expressed over whether such a structure could be constructed with the slipforming technique. To demonstrate that this was actually feasible, a “leaning tower” was cast in the Jåttåvågen district of Stavanger and stands there to this day. Nevertheless, the Tripod was not selected. Instead, the choice fell on a four-shaft concept – which was still an impressive sight, and far beyond what many commentators thought could be constructed.

Dealing with the gas

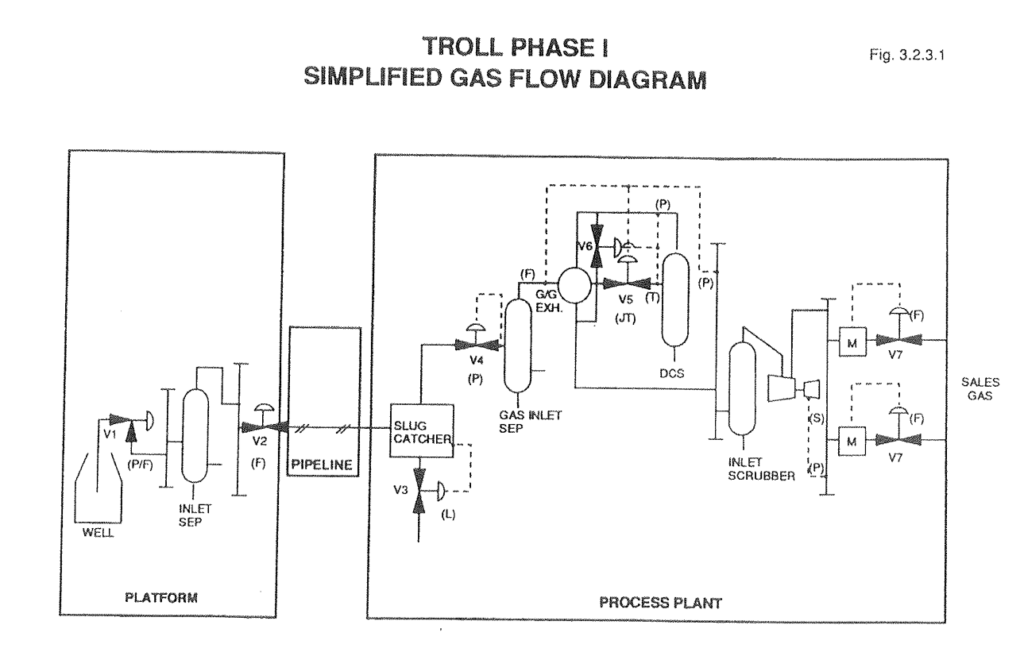

Troll gas is good quality, comprising 93 per cent methane. But heavier hydrocarbons and water still needed to be separated out before delivery to the buyer. Additional compression was also needed to drive the gas the whole way to continental Europe.

Such processing and compression called for a big plant on the platform, which was expected to consume 1.7 million standard cubic metres (scm) of gas per day.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Troll Field – plan for development and operation. Phase one gas, September 1986, A/S Norske Shell.

While sales talks on Troll gas were being pursued with Gaz de France among others, Statoil also secretly negotiated an agreement for gas from Sleipner. To add piquancy to the whole proceedings, French oil company Elf rather than Gaz de France was a key counterparty to these discussions. But the French government intervened in the final phase of the Sleipner talks and forbade Elf to continue. If France was to take large Norwegian gas volumes, it had to be through Gaz de France. That created complications and a revised PDO which reduced capacity on the Troll platform. However, this reduction was not implemented after Gaz de France agreed to buy from both Sleipner and Troll.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, 1996, Troll: gas for generations; Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk oljehistorie.

Cheaper and better

The development solution for the process plant nevertheless turned out to be different from the one first envisaged. That was not least due to the ideas proposed by Arild Volden. His long experience included assistant field manager for Frigg before joining Statoil in 1983. He became more and more concerned about the dimensions of the platform, and was convinced that it was both technically feasible and better financially to bring the gas ashore for processing. Several attempts to launch this idea internally encountered resistance, in part because the cost overruns at the Mongstad refinery were mounting and the willingness to accept large-scale technical innovations was small.

Although landfall studies for Troll were not supposed to continue, Volden secured acceptance for carrying on with plans to convert the gas compressors on the platform for electrical operation and to adopt subsea solutions for oil wells.

A widespread belief was that transporting gas and water as a multiphase flow in the same pipeline would present a big challenge. Long-distance transport of unprocessed gas with heavier components and water could cause pipeline corrosion, and Troll was due to produce for many years. Volden disagreed, and claimed that the land terminal could be placed even further away without any problems in terms of corrosion and the multiphase flow. He was so convinced that dewatering, compression and onward export to Europe had to be done at and from an onshore plant that his colleagues at Statoil’s Bergen office nicknamed him “Troll on land”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor, 2021, 25 år med Troll gass. Eventyret fortsetter.

His arguments for landing the unprocessed wellstream included:

- safety – less processing and fewer people offshore

- operating costs – a simpler offshore installation meant less maintenance

- lower topside weight would give a cheaper and simpler structure

- development costs – opportunities to starting building onshore later and thereby postpone spending

- expansion – opportunities for capacity increases at an onshore plant and tie-ins to other fields.

A final look

Volden became the first Troll employee at Statoil’s Bergen operations division (DDB) in Sandsli, an appointment symbolically enough reported in the same issue of house journal Status as Arve Johnsen’s resignation as the company’s first CEO. His departure and replacement by Harald Norvik opened new opportunities to review the chosen development concept. Projects which could help to change the negative impression created by the Mongstad overruns were suddenly more welcome. Volden’s big idea again moved up the organisation, all the way to Norvik. He has recalled this as follows:

Troll was one of the first issues I came into contact with after taking over at Statoil. Development preparations were well under way, with Norske Shell in charge. After an internal process in Statoil’s management, we decided that we should take one final look at landing the Troll gas in Norway. The oil industry was making positive progress in developing new technology, while we had all become more concerned with costs and profitability. The climate for doing something with Troll was good … Engineering of Troll had already advanced very far, and I was fully aware that success depended on reaching top-level agreement in the companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, op.cit.

He decided to raise the landfall issue at a meeting between top-level representatives from Norske Shell and Statoil in the spring of 1989. It was agreed to assess the issue jointly and, after detailed studies, the decision was taken to bring the unprocessed gas ashore. Norvik has subsequently said it was one of his proudest moments that Statoil succeeded in amending a project at such an advanced stage and with such a heavyweight operator as Shell.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Borchgrevink, Aage Storm, 2019, Giganten, fra Statoil til Equinor.

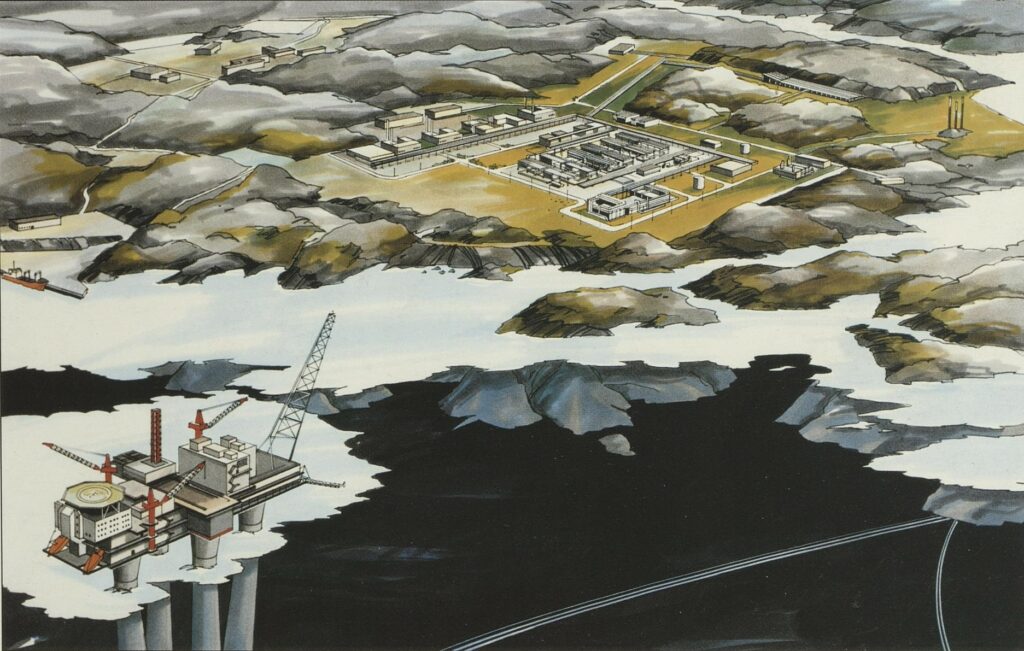

The Troll licence resolved on 15 March 1990 that the A platform would not be fully integrated, but that its process facilities would be moved ashore instead. Kollsnes in Øygarden near Bergen was eventually chosen as the landfall site. That naturally had huge consequences for this local authority, and supplemented the Sture oil pipeline terminal on the other side of the island.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor, 2021, 25 år med Troll gass. Eventyret fortsetter.

Since the original plans had already received a government go-ahead, a new PDO had to be prepared and approved. This was drawn up by Norske Shell in close consultation with Statoil and submitted in May 1990. It explained that extensive studies had found landing the gas for dewatering to be the preferred option and associated condensate would be exported from the Sture facility.

First electrification

Landing the gas freed up substantial space on the platform, which in turn permitted another innovation on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) – electrification of an offshore installation. Another factor contributing to this decision was that Norway in 1989 had an annual hydropower surplus of 2.5 terawatt-hours (TWh), with Troll and Kollsnes expected to require 1.7 TWh per annum.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, op.cit.

Delivering electricity to Kollsnes unleashed intense discussions, including protests about overhead transmission cables. The solution was to run 15 kilometres of the 300 kilovolt cable below ground across Sotra and in Øygarden – a unique approach in Norway during the 1990s. More than 1 500 kilometres of power cables were laid in the terminal area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor, 2021, 25 år med Troll gass. Eventyret fortsetter.

The daily 1.7 million scm of gas originally scheduled for running the platform now also became available for sale. When the Norwegian government later imposed a duty of NOK 0.6 per cubic metre of carbon dioxide released from oil and gas production on the NCS, the commercial justification for relying on electricity was further strengthened.

Smaller platform, more pipelines

The new topside weight for Troll A was now 26 500 tonnes, a substantial reduction from the original plan. Two 36-inch pipelines would transport the unprocessed gas to Kollsnes for dewatering and removal of the condensate, while a four-inch line carried glycol antifreeze back to the field for mixing with the gas to prevent internal corrosion in the pipelines to Kollsnes.

These transport facilities lie almost entirely on the seabed. In the shore zone, however, they have been run through a tunnel for the final kilometres up to the plant in order to avoid bad weather and exposed locations. That represented a major project in itself.

In addition to an increased capability to deliver 23.7 billion scm (Gscm) of gas per annum to Europe, the Troll sales agreements committed the sellers to have spare capacity equal to 14 days of consumption in the event of an unexpected plant shutdown. To make good on this promise, gas storage was constructed at Etzel in Germany to hold about 500 million scm. This was later expanded to 1.2 Gscm.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/en/what-we-do/terminals-and-refineries/etzel.html.

Big celebrations were held in Øygarden when the Kollsnes plant opened on 19 June 1996. The guests, including HM King Harald V, were served wine which had been bought as early as the mid-1980s and specially stored for this occasion. Gas flowed in from the platform just over 60 kilometres out to sea while electricity was transmitted in the other direction. Pioneering giant Troll A was thereby in swing with deliveries to continental Europe.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, Bjørn Vidar, op.cit.

arrow_backVeslefrikk – recycled floaterThe toughest strikearrow_forward