Exploration in New Zealand

Strengthening Statoil’s global offshore positions was a clear priority under Helge Lund’s leadership in 2004-14. The aim was to secure access to new acreage with a high potential, and to drill in both growth areas and frontier regions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2013, Statoil.

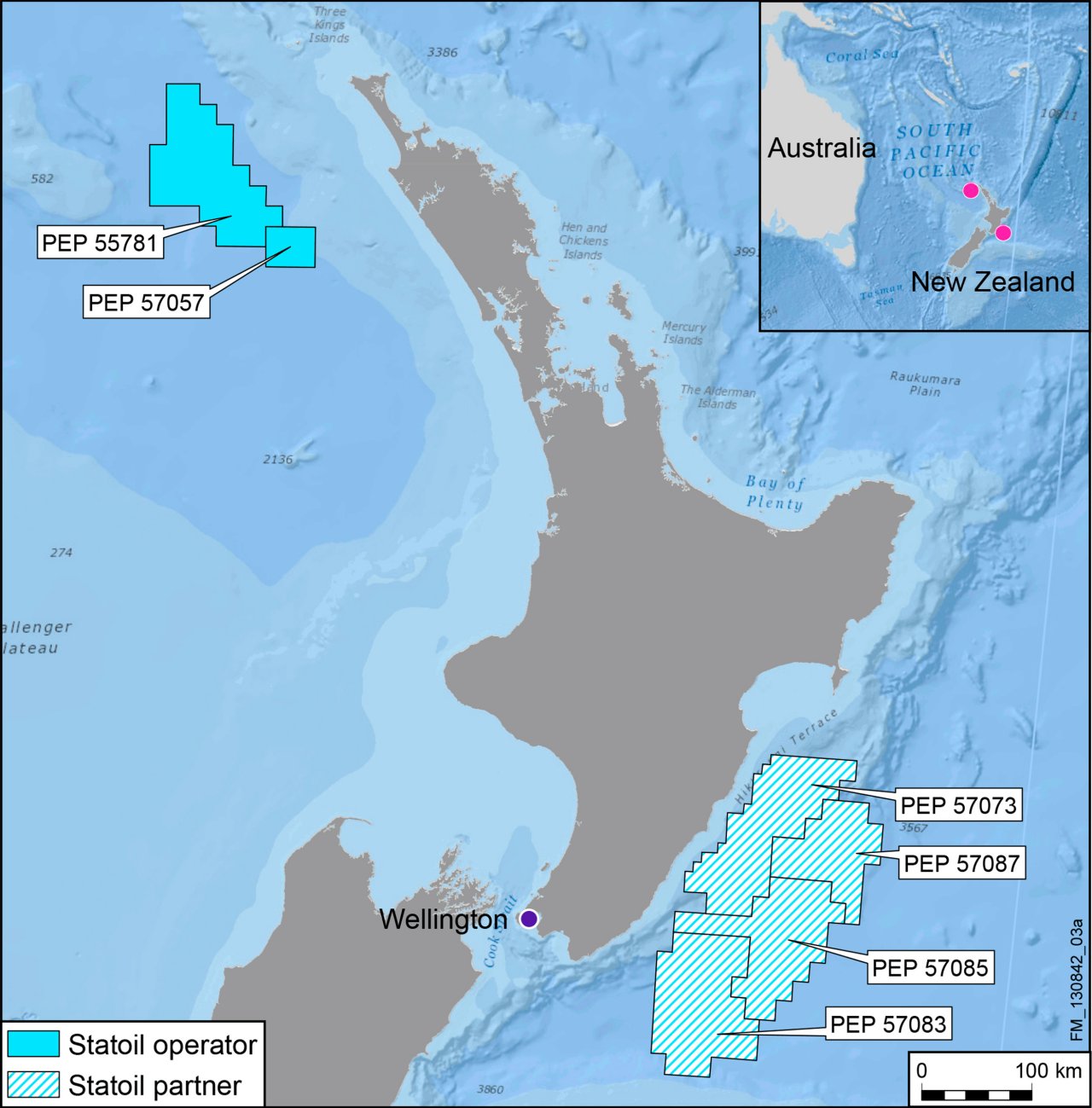

New Zealand provided a typical example of the latter. In the early 2000s, the country wanted to map its opportunities for producing oil and gas. That ambition was expressed by Simon Bridges, the National Party minister of energy and resources, in connection with the award of exploration licences in 2013.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 5 December 2013, “Statoil-offensiv i New Zealand”. It therefore fitted hand-in-glove with Statoil’s strategy when the company was awarded a licence with Australia’s Woodside Petroleum Ltd in the Reinga Basin, which lies some 85 kilometres off North Island in the Pacific.

In 2014, Statoil also secured three licences together with Chevron – the second-largest US oil company – off the south coast of North Island.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 12 June 2017, “Statoils oljedrøm i New Zealand møter kraftig motstand”. Erling Vågnes, exploration head for the eastern hemisphere, was satisfied – this was fully in line with the company’s strategy.

Seismic surveys and drama

Offshore oil exploration was controversial in New Zealand. A few days after the 2014 licences had been awarded that December, Greenpeace took action. Its activists blocked the entrance to Statoil’s offices on the 21st floor of the Vodafone building in Wellington with additional locks and wooden planks.

The environmentalist organisation had collected 19 000 signatures on a petition against the company’s plans for possible future petroleum production. It claimed large parts of the country’s population were worried that seismic surveys would harm whale and dolphin populations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: E24, 10 December 2014, “Statoilskontor på New Zealand sperret av”.

Seismic surveying nevertheless continued. After having studied the resulting data from the search area off the Northland region in 2016, however, Statoil decided to relinquish the licence to the Crown.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Offshore Energy, 14 October 2016, “New Zealand: Statoil abandons offshore exploration project”; NTB, 14 October 2016, “Statoil trekker seg ut av New Zealand”.

Strong Maori opposition

Exploration was also pursued on the southern side of North Island, where Statoil had 30 per cent of another licence with Austria’s OMV as operator. This activity met great opposition from the indigenous population. Like their counterparts in Canada and Australia, representatives of the Maoris attended Statoil’s annual general meeting in Norway to protest against operations they feared would harm stocks in their traditional fishing grounds.

In June 2017, they also brought a petition with 23 000 signatures to the UN’s ocean conference in New York and asked Statoil to withdraw from New Zealand.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 12 June 2017, op.cit.

The Maoris received moral support from Norway’s indigenous Sami population, which pointed out that Statoil was breaching human rights through its activities in New Zealand. That was the message in a letter sent by the Sami Parliament and signed by its president, Aili Keskitalo, to New Zealand premier John Key. It was copied to several ministers in his government, as well as to Statoil and Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

Knut Rostad, Statoil’s press spokesperson for foreign operations, gave the following answer when asked by Norwegian technical journal Teknisk Ukeblad whether the company complied with New Zealand regulations and the UN’s guidelines: “It’s important for us, regardless of where we are, that we do this in a responsible way. We take note of their views. We have kept them continuously informed about our activities, and will continue to do so in the time to come.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Teknisk Ukeblad, 30 September 2015, “Sametinget frykter Statoil bryter menneskerettighetene. På New Zealand.”.

Statoil and Chevron continued their exploration work in the four licences they held off North Island in 2015 and 2016.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Offshore Energy, 14 October 2016, “New Zealand: Statoil abandons offshore exploration project”.

Oil crisis and new strategy

Eldar Sætre took over as CEO of Statoil in 2015. While Lund had served at a time when high and rising oil prices yielded good profitability, his successor had a price slump dumped right in his lap. Operating profit in 2015 was down by 86 per cent from the year before. The company had to downscale after several years of generous spending on new investment.

Nevertheless, the strategy for foreign operations did not change overnight. The goal in 2015 was still to develop substantial and profitable international positions. But the persistence of low oil prices over several years, with little sign of an upturn until 2018, meant there was little scope for new capital spending.

No new licences

The political shift after New Zealand’s 2017 general election changed the parameters for oil operations there. Labour’s Jacinda Ardern became prime minister with support from the Green Party.

Until then, 22 licences had been awarded which provided opportunities to pursue petroleum production for 40 years in the event of a discovery. New Zealand was regarded as an environmental laggard. It had made no promises of CO2 cuts under the Paris agreement. On the contrary, the country had signalled a 44 per cent increase in emissions from 1990 to 2030.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/new-zealand/.

With a new government in place, this climate policy came under the microscope. Legislation committing the country to be climate-neutral by 2050 was passed, and the annual award of offshore oil and gas licences was cancelled in 2018. No new rounds would take place under the sitting government.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Teknisk Ukeblad, 12 April 2018, “New Zealand dropper å dele ut nye oljelisenser av hensyn til klimaet”.

That perhaps contributed to the decision by Chevron and Equinor in 2019 to relinquish their three licences off the east coast of North Island. The 25 000 square kilometres concerned represented a quarter of the country’s active exploration acreage. Although the licences ran for 15 years, neither company wanted to continue exploration because both wanted to consolidate their operations.

Bryn Klove, Equinor’s country manager in New Zealand, felt that many people would speculate that the decision to pull out reflected the changes in the country’s exploration strategy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NZHerald, 18 June 2019, “Chevron, Equinor depart NZ exploration scene”. However, the companies had not got as far as drilling yet. Equinor’s strategy of concentrating on core areas represented the weightiest reason for its departure.

arrow_backFrom Statoil to Circle KSuriname in South Americaarrow_forward