Little gender equality in the 1970s

The first Statoil board had no female members, and its CEO was naturally a man – so well known in Norway that his name hardly needs mentioning. It went almost equally without saying that his secretary was a woman.

This article provides some examples of what equal opportunities looked like for the first women employed by Statoil.

Mostly young secretaries

Marit Falck, hired as CEO Arve Johnsen’s secretary in November 1972, was the company’s second employee and is often highlighted for that reason.

She was both typical and untypical of the first females to join Statoil. What distinguished her from other women who were hired was her mature years. Falck had attended commercial college and wanted to get a job after her children had become older. Starting as Johnsen’s secretary, she went on to become a personnel secretary along with Else Grethe Kolnes. That involved to a great extent securing accommodation for all the new employees, and even acting as a furnishing consultant. To expand her expertise, Falck qualified in personnel administration at the Rogaland Regional College.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status house journal, no 22, vol 2, 1975.

Typically, Falck had little in the way of higher education. Reading Statoil’s Status house journal from the 1970s gives an overview of those joining the company. The impression is that they were largely men. A great many of them were engineers in their 20s and 30s. But the very youngest recruits were women, often recently graduated from commercial or secretarial college. Some were only 17 years old. Secretaries were employed to operate the telephone switchboard, take dictation, do typewriting and keep the timetables of their male colleagues in order.

The personnel department had the highest proportion of female staff, and a number of women also worked in the information department. That included Berit Rynning Øyen, who was a journalist and editor of Status.

Where women meant bad luck

Rynning Øyen visited the Norskald rig for the information department on 18-19 June 1975. This unit was then drilling on Statfjord, where Statoil was the biggest licensee and Mobil the operator. At that time, not many Norwegians knew how an oil well was drilled in the North Sea. The purpose of Rynning Øyen’s visit was to photograph the work and people employed there, and to provide an impression of the environment when they were off duty. But her presence proved far from uncontroversial.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 12, vol 2, 1975.

“There was a massive row,” she recalls. “Mobil’s offshore installation manager claimed that having women and horses on a rig meant bad luck, and asked several times if I didn’t want to return home the same evening. He proposed requisitioning a helicopter from Flesland [outside Bergen] just to get me ashore. That this would be very expensive was of no concern.” He clearly did not want her on board as the only female among 70 men.

Rynning Øyen did not want to go, and called Johnsen, who told her just to stay put. Norwegian laws and regulations were the ones which mattered, although the country did not get its first gender equality Act until four years later. Rynning Øyen stayed, but was not allowed to remove her coverall when going in to eat. She found the crew pleasant and was well looked after. A berth was provided in the sick bay, the only cabin with a lock on the door and therefore the safest place for a woman. But she nevertheless felt a little concerned, since the lock had been meddled with a few days earlier. It was now repaired and reinforced. But all went well, with a guard posted outside her cabin during the night. The stay proved a success, and Rynning Øyen got the shots she wanted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Berit Rynning, Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 7 May 2020. But conditions were obviously not designed for women.

In the longer term, provision for females offshore improved after the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) made it mandatory in 1979 to have separate changing rooms for women on rigs and platforms.

Engineer on the defensive

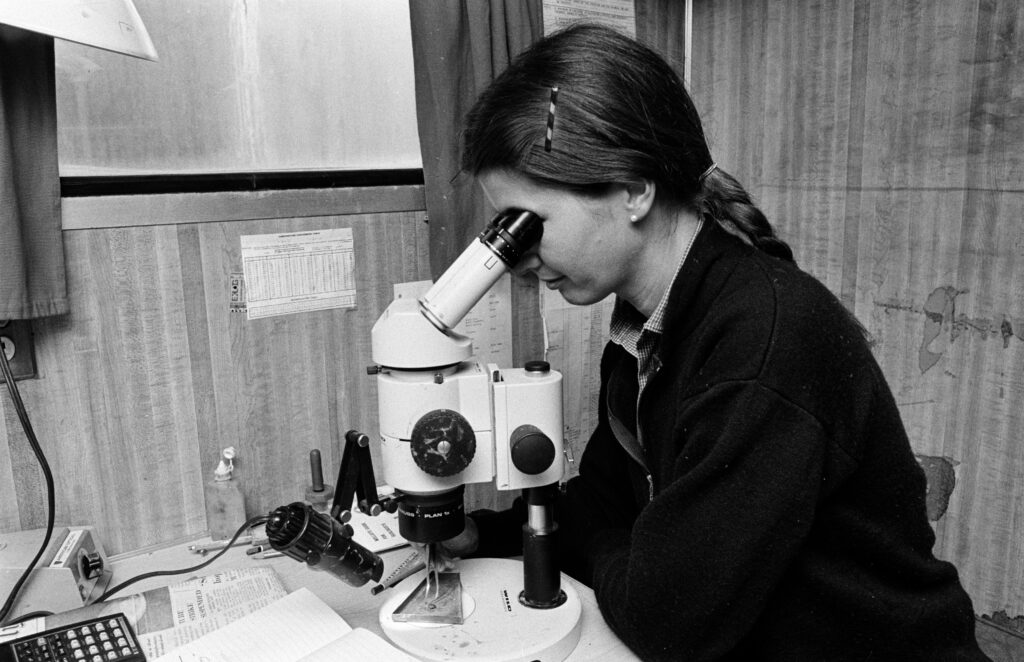

One employee who received a particularly long presentation in Status was Ingjerd Borsheim. While others were profiled in two-three lines, she was given almost a full page.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 20, 1975.

Borsheim ranked as Statoil’s first female chemical engineer, recently graduated with an MSc from the Norwegian Institute of Technology (now the Norwegian University of Science and Technology) in Trondheim. The 25-year-old was to be one of Statoil’s two representatives in the group due to plan the construction of a cracker at Rafnes south of Oslo. She would work there for a couple of years during the planning, construction and start-up phases, and become familiar with Statoil partners Norsk Hydro and Linde in Germany.

Her qualifications for the job were indisputable. In addition to her MSc studies, she had taken an environmental protection course, been a researcher at Sintef and served as a scientific assistant in the department of technical electrochemistry.

Nevertheless, Borsheim often felt she had to defend her choices and position because she was a woman. “The bulk of Statoil’s employees are young men, but they start talking about women’s lib as soon as they see me,” she told Status. She explained that she had never belonged to any feminist organisation – not because she disagreed with their goals, but because she felt that the issues they raised were minor and insignificant. She had chosen to study chemical engineering after upper secondary school on the basis of her interests and abilities – and felt that ought to be fine and not worthy of comment.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Medic on Ross Rig

Working conditions for parents of small children in Statoil on land were improved with the opening of a day-care nursery for employees in 1974-75. The company also helped to fund a home help scheme, and flexible working was introduced.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, annual report of the works council, 1974.

Women began to make their entry offshore. The first female worker started work on 10 January 1977 on Ross Rig, Statoil’s initial drilling unit. This was then drilling the company’s first well as operator on block 1/9 just south of the Ekofisk field.

Typically, the first women employed offshore was a medic. Aged 37, Anne J Sandell was born in the Netherlands and had lived in Norway for 14 years. She was well qualified for the job, having experience as an operating-theatre nurse at Vest-Agder Central Hospital as well as a course on treating diving injuries and sickness.

The Ross Rig job was very different from working in a hospital. Sandell combined the job of medic with a post as a storekeeper. Nor was she used to the tour system – 14 days offshore and 14 on land.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status, no 2, 1977. Nevertheless, she wanted to see if the job of medic/storekeeper could be combined with family life on land.

Gender-defined

These examples provide an insight into the opportunities and limitations which existed for females in the offshore industry 50 years ago. Incidents which serve as amusing anecdotes today were real barriers and constraints for women in the 1970s. With hindsight, it might seem both surprising and shocking that employment in Statoil was so gender-defined. This was quite clearly a time when breakthroughs were made for female participation, particularly offshore. But it helped that the CEO believed women had their place in every type of job they were qualified to do.

arrow_backGetting the oil hunt organisedConstruction of Statfjord Aarrow_forward