Diving research to make the impossible possible

The problem faced was the need to cross the deepwater Norwegian Trench which runs between the coast of western Norway and the oil and gas fields in the North Sea.

A test dive to 320 metres was due to take place in the Skånevik Fjord near Bergen early in February 1978. This marked the first attempt to weld together two pipes at that depth. If it succeeded, the trial would set a world record. Where its funders were concerned, it would be equally important in showing that gas could be landed in Norway – an important political goal.

Skånevik trial

Norwegian oil company Norsk Hydro was operator for the dive together with Statpipe operator Statoil, while several foreign oil companies supported the NOK 40 million project.

Major US contractor Brown & Root was responsible for conducting the trial, and hired America’s Taylor Diving and Salvage Company to perform the actual dive and welding operation. The latter was highly experienced, and had been carrying out welding on subsea pipelines using the saturation diving technique since 1972. In preparation for the Skånevik test, the company performed four simulated work dives in 320 metres of water at its own research facility in New Orleans.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Deepwater hyperbaric welding program, information film.

The Sintef research foundation in Trondheim was involved from the Norwegian side, while the welding procedures were approved by classification society Det norske Veritas (DNV). A representative from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) was also present.

Despite thorough preparations, however, things went wrong. In the late evening of 7 February 1978, American diver David Hoover died in 320 metres of water. He was one of three members of the first team sent down to the work depth in the diving bell in order to weld the pipes together in a dry chamber (habitat) on the seabed. Midway through the dive, operators in the control room lost contact with Hoover. He was discovered lifeless by his two team mates, who drew him into the bell and began resuscitation efforts. These proved fruitless. This tragic fatality was probably the result of a technical failure in the supply of breathing gas. The dive was cancelled and a police investigation launched.

Statoil and Hydro withdrew from the trial, but Taylor Diving, Brown & Root and the divers wanted to continue. They transferred to Scotland and successfully completed the welding job in 320 metres of water.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Ryggvik, Helge, 2009, On the Edge, Under Water. Offshore Diving in Norway: 203-209.

The divers, who had experienced the loss of a colleague, spent a total of 44 days in the cramped compression chamber at work depth pressure. This was an unusually long period, but nevertheless approved by the medical specialist supervising it. Given that the fatal accident had revealed weaknesses in the technical equipment, a considerable risk was taken in completing the diving trial in Scottish waters – albeit successfully.

Diving research in Norway

The question was whether the necessary diving expertise could be developed in Norway in order to end reliance on foreign contractors. This idea matured gradually during the 1970s. In 1978, the year Statfjord A came on stream, the Norwegian Underwater Institute (NUI) was established at Gravdal in Bergen as a national research facility. The government and heavyweight Norwegian industrial interests – with DNV in the lead – were the drivers in creating this centre for subsea technology and hyperbaric medicine.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 243-245.

At the time, the challenges faced in piping gas from the Norwegian share of the Statfjord field in mainland Norway and on to Europe were approaching a solution. A favourable gas sales agreement was reached between Statoil and Germany’s Ruhrgas. Statpipe would carry this commodity to Kårstø north of Stavanger for processing, with the dry gas continuing to the continent via Ekofisk and the Norpipe line.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk oljehistorie: 66.

Aiming to overcome the challenges of deep diving, the NUI was in full swing from 1980 with research programmes funded by oil company assignments. It set a depth record – still unbeaten in Norway – of 504 metres with the Deep Ex II dive as early as 1981.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin Øye og Ryggvik, Helge, op.cit: 248-260.

In that year the institute was converted into an independent foundation and renamed the Norwegian Underwater Technology Centre (Nutec).

DNV and the Norwegian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (NTNF) were joined as owners by Statoil, Hydro and Saga Petroleum. These three Norwegian oil companies all had plans for pipeline activities and operations across the Norwegian Trench. That the owners of the centre were also users of its results eventually gave rise to a number of issues related to research ethics.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 260-262.

Among other questions, the board discussed whether research dives needed ethical clearance by an independent commission. But the medical team at Nutec was very clear here – such approval was always required.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stein Tønjum in conversation with Kristin Øye Gjerde, 25 April 2008.

Statpipe research dive

The goal of laying pipelines across the Norwegian Trench to land petroleum in Norway had still not been reached. A great deal was at stake, and several test dives were conducted in 1983-84 so that the Statpipe project could be approved.

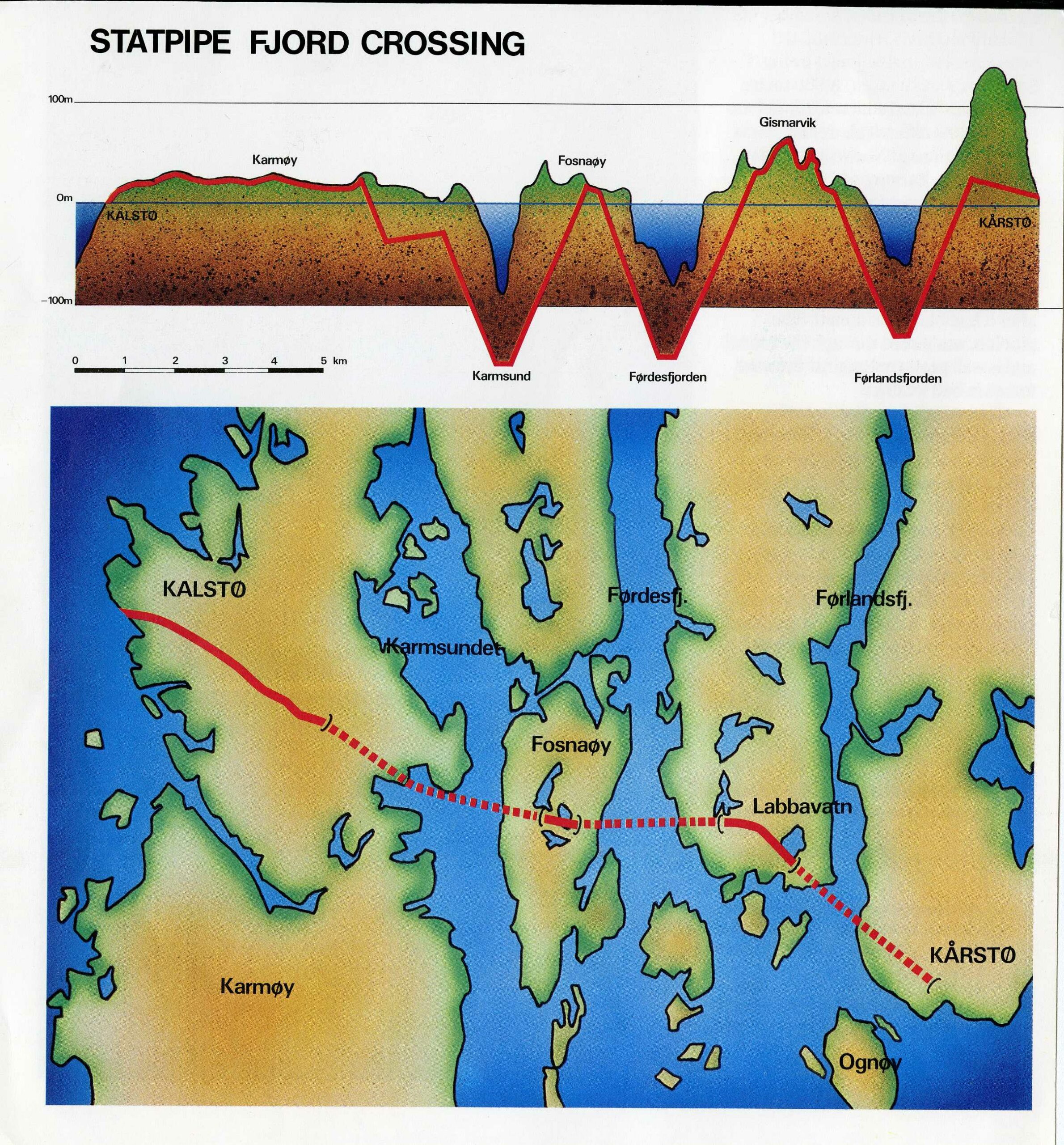

Two diving contractors were hired – France’s Comex and Norway’s Seaway Diving, part of the Stolt Nielsen group. The first would support pipelaying from Statfjord towards Kårstø, while the latter was to cover work from the edge of the Trench to the initial landfall at Kalstø on Karmøy island.

A welding dive to 300 metres was carried out at the Comex premises in Marseilles, with Nutec as a sub-contractor, while two test descents to 350 metres were made at the Bergen centre.

In the latter cases, six divers were put under pressure corresponding to the work depth. They were divided into two teams, each working seven hours a day in Nutec’s big wet chamber. The whole operation took 18 days and was hailed as successful by the project management.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Pedersen, Odd, 2001, Best på bunnen: 84.

A series of dives was also staged by Seaway Diving in the Onarheim Fjord using a pre-damaged 72-metre gas pipeline laid on the seabed. The divers located the problem, removed the concrete coating with its reinforcement bars and corrosion protection, cut the pipe and plugged it against gas flow before welding and heat treatment. This work was conducted in a 60-tonne habitat with gripping and welding equipment, specially built for water depths down to 300 metres and available for the Statpipe project. It could be lowered onto the pipe and, once the bell had been locked to the unit, specialists were able to enter in ordinary boiler suits. Trials on the seabed covered welding, ultrasonic checks and re-applying a protective coating to the pipe. The equipment could be deployed from any diving support ship.

Seaway Diving’s divers were intended to form part of the emergency response when laying Statpipe, with a deepest point of 297 metres. Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) would primarily be used, with divers ready to intervene if anything went wrong.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Haugesunds Avis, “Vellykket Statpipe-test på 300 meters dyp”, 3 September 1983.

Just as with early trial dives, Statpipe also presented challenges. The NPD accordingly approved diving down to 250 metres for the pipeline. That allowed the laying operation to begin.

Aftermath

Big investments put Nutec in financial difficulties, since the offshore industry failed to provide enough work for the centre to pay its way. The solution was for the oil companies to take it over completely. Statoil owned 60 per cent, Hydro 30 and Saga 10. They were represented on the board by Jon Husly, Torleif Enger and Bo Brennstrøm respectively. The danger was that the oil companies thereby increased their opportunity to influence research findings, and critical voices began to be heard.

Jan Jacobsen in the Energy Divers and Service Association commented in 1985: “It represents a disaster for diver health and safety when Nutec, as our only research centre in these fields, is in danger of losing its position as a free and independent brake on the companies’ drive towards using divers in ever deeper water.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Petro Magasinet, no 2, 1985 ”Ta et oppgjør innen dypdykkingen i tide!”: 20.

Putting the oil companies in control of diving research was compared with setting a fox to guard the chicken coop. Calls were made for the NPD to monitor that this work was being carried out in a suitable fashion before people taking part in the experiments were harmed.

The criticism suggested that the depth limit for acceptable diving had been reached. After several test dives in the 1980s, the NPD set this figure at 400 hundred metres. But nobody ever went that deep. The NCS record was 248 metres on Statpipe. And diving on the NCS was gradually phased out in the 1990s. ROVs capable of replacing divers were developed, along with automated welding machines for pipeline repair.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Pedersen, Odd, op.cit: 84.

It is also worth noting that the depth limit for safe diving was reduced in practice to 180 metres in 2000. That put an end to the exploitation of divers for such purposes as crossing the Norwegian Trench with oil and gas pipelines.

arrow_backConcrete’s dominance – the Gullfaks caseThe Volvo agreement – almost Volvoilarrow_forward