Discovering Johan Castberg

The operations room in the Medkila office was full of people on the morning of 1 April, as geologists, geophysicists, petrophysicists and others followed the logs ticking in from offshore with a mix of hope and fear.

Statoil had played the leading role in exploring Norway’s Barents Sea sector, but a long time had now passed since Snøhvit and the associated Albatross and Askeladd fields were found. This was the only commercially interesting find in the Barents Sea apart from the Goliat discovery by Agip – later Eni and then Vår Energi. Both lay in the Hammerfest Basin, and all subsequent exploration outside that geological area had been unsuccessful.

Traces of petroleum which once filled a reservoir but had already leaked out were repeatedly encountered. “We’re a few million years too late,” was a frequent lament. To add to the pressure, the four wells drilled so far in 2011 were all dry. Skrugard could be the last throw of the dice in the Barents Sea.

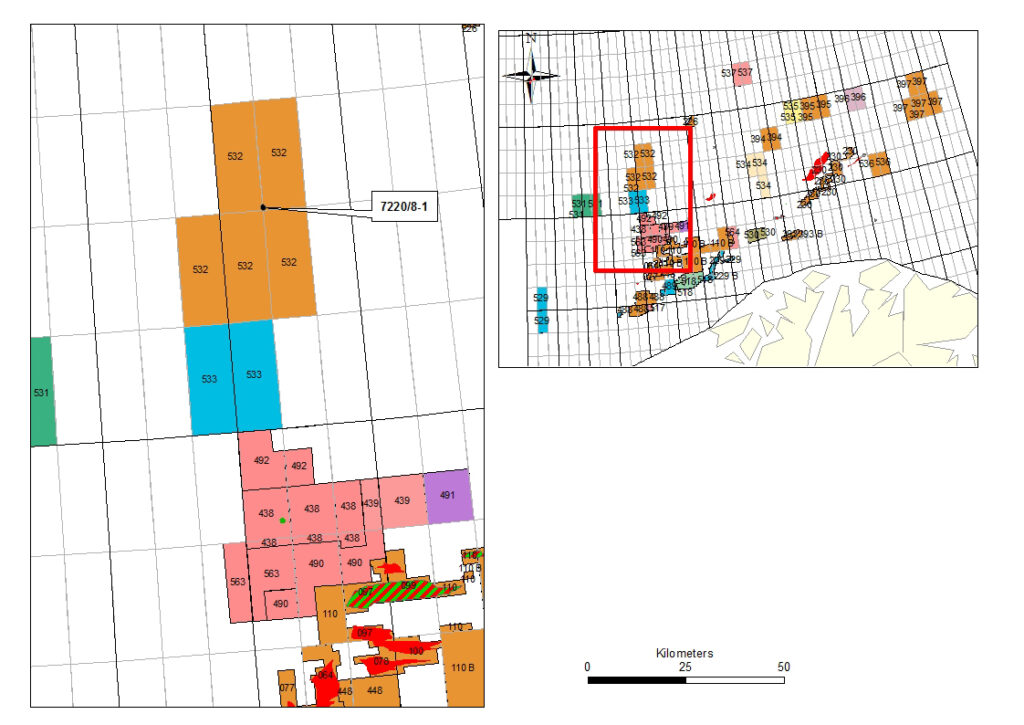

Production licence 532 covered an area of the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) sought earlier by Det Norske, but not awarded until the 20th licensing round in 2009. Statoil was the operator, with Eni and Petoro as partners. This choice was unlikely to have been arbitrary. Statoil and Agip/Eni were actually the only two companies which had operated wells in the Barents Sea during 1993-2011 – even though it was now clear that more companies would be trying their luck in the far north. Located 220 kilometres from land, Skrugard was the most promising potential reservoir structure to be drilled in these waters for a long time. The seismic data revealed unusually clear signs that both oil and gas could be present in large quantities.

Soon after PL 532 was awarded, a decision was taken on where the wildcat (the first well on a prospect) was to be drilled. Planning then began, along with the search for a drilling rig suited to Arctic waters. That took time, and it was not until February 2011 that Polar Pioneer – a semi-submersible specially built for far northern operations – arrived on location to drill 7220/8-1 in 374 metres of water.

Knut Harald Nygård, Statoil’s exploration vice president for the Barents Sea, was on the offensive, and suggested that “old” customs involving champagne and cigars could by all means be revived if Skrugard proved to hold petroleum. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Harstad Tidende, 2 March 2011.

Expectations were high and the potential for failure great. Things were serious now.

Moment of truth

Drilling down to the reservoir depth, about 1 250 metres beneath sea level, progressed without major problems. On the morning of 1 April came the signal everyone had been hoping for – but none had dared to expect. The logs collecting data from the well indicated the presence of both oil and gas at the expected depth. After coring and more detailed well logging, confirmation was secured that the discovery involved 150-250 million barrels. This had a sales value of NOK 100-165 billion at 2011 oil prices and NOK/USD exchange rates, enhanced because the light oil was of good quality. The gas cap in the reservoir could also have a commercial potential. As important as the actual discovery was the fact that it opened a whole province to exploration. Statoil, it was said, had “found the key to the Barents Sea”. After many lean exploration years on the NCS following the Ormen Lange gas discovery in 1997, better times could now be hoped for.

“This generates many new opportunities,” said Tim Dodson, Statoil’s executive vice president for exploration. “We’re only at the starting line. It’s one of the most important discoveries on the NCS for the past decade.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Harstad Tidende, 2 April 2011.

It also proved to be one of the largest finds worldwide in 2011 – which admittedly ranked as a lean exploration year globally, even if it was positive for Statoil.

Other observers, such as Norwegian oil market analyst Torbjørn Kjus, were more restrained. Kjus noted that, even if this was good for Statoil and Norway’s oil industry, 10 such discoveries were needed to replace a field like Oseberg.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 2 April 2011.

Given Norwegian production at the time of two million barrels per day and daily global consumption of 85 million barrels, Skrugard would in theory extend the oil age by 125 days for Norway and by three days for the world.

Although 10 identical structures were not located nearby, there was no lack of follow-up potential. Just days after the Skrugard discovery, planning began for the next wildcat on the neighbouring Havis prospect.

This structure lies further to the west and in deeper water – but was more than a neighbour, according to Nygård: “This is a twin.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finnmarken, 28 December 2011.

And Havis proved to have virtually the same content as Skrugard when its discovery was confirmed a few days into 2012.

Afterwards, Nygård admitted that a duster (dry well) on Skrugard would very probably have spelt the end. “Had it been dry, faith in the Barents Sea would have been hard to sustain,” he said. “It was life or death.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finnmarken, 28 December 2011.

In the wake of success

A number of exploration wells were drilled around Skrugard and Havis, yielding both disappointments and encouragements. All these prospects were named after various ice features, such as Nunatak, Isflak (ice floe), Isfjell (iceberg), Iskrystall (ice crystal) and Drivis (drift ice). The total estimated volume of oil in the finds made is 400-650 million barrels, and petroleum and energy minister Ola Borten Moe gave the name of Johan Castberg to their coordinated development.

General exploration activity in the Barents Sea also picked up, with some 69 wells drilled after the Skrugard find. Roughly half of these found oil and/or gas. But only a handful of them were commercial. In addition to Johan Castberg itself, Wisting further to the north-east is the only discovery where a development is planned.

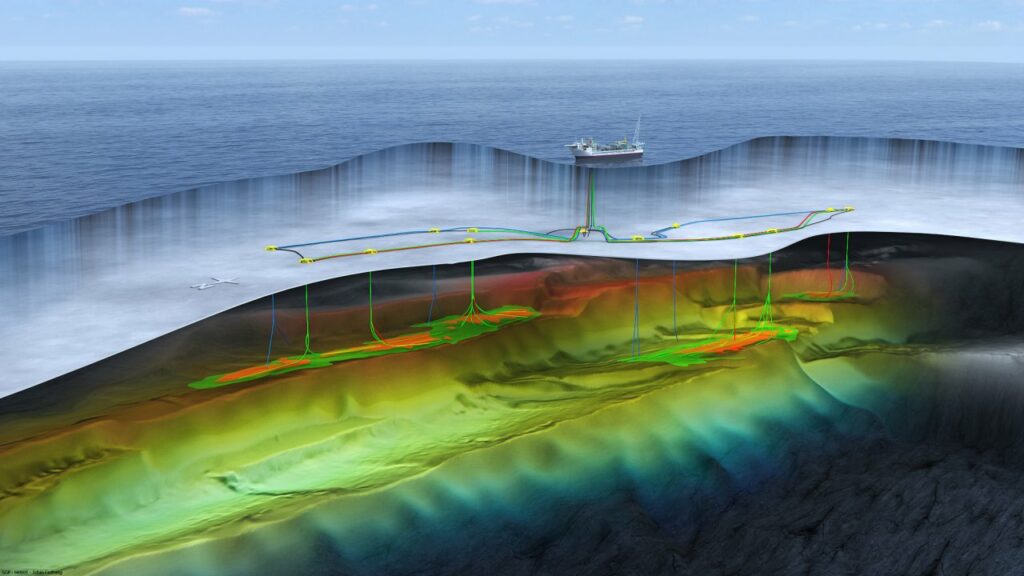

Riding a wave of success and with petroleum in the ground, Statoil continued studying and planning a Castberg development. But the first ambitions of getting on stream within five years proved over-optimistic. At the time of writing, in 2022, plans call for first oil to arrive “on deck” in 2023. After a number of studies and unclear communication about the development solution, as detailed in a separate article, Statoil opted for a floater. This means that the oil will be produced via subsea wells to a floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) unit and shipped ashore by shuttle tankers. The field’s planned producing life is 30 years.