Johan Castberg to land – or not

Oil companies and a supply base were admittedly to be found in Harstad, and oil-related activities in Tromsø. Hammerfest had also secured the Snøhvit landfall and the gas liquefaction plant at Melkøya as a welcome supplement. But a lot of people felt the positive spin-offs from offshore operations were smaller than those they could see further south.

Petroleum and energy minister Ola Borten Moe also presented plans in April 2013 to open the Barents Sea South-East area for exploration. This was the former “grey zone” of overlapping boundary claims, which Norway and Russia reached agreement on in 2011. Many residents of eastern Finnmark county in the far north envisaged a dawning golden age. “People are now coming who will spend money and sell their services on land,” proclaimed Remi Strand, CEO of Arctic Development AS. “Cooks, car mechanics and others who can provide basic services will be required – not just engineers.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finnmarken, 24 March 2013.

Export solutions for oil

Skrugard lies 250 kilometres north-west of Hammerfest, in the western Barents Sea. Its discovery created expectations in northern Norway. Statoil’s exploration office in Harstad sighed with relief after having been threatened with closure. But people further north in Finnmark also hoped the discovery would bring jobs and revenues. The operations office for the planned field development was placed in Harstad but, as the Havis, Drivis and Skavl discoveries were also brought under the Johan Castberg mantle, hopes grew for a landfall in Finnmark which could create local jobs and value.

Several possible models were assessed for exporting the Johan Castberg oil:

- direct export from a floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) unit by shuttle tankers

- an oil pipeline to land for onward transport by tankers

- an intermediate solution with specially tailored shuttle tankers carrying oil from the field to a transhipment terminal on land for loading into larger conventional carriers.

The 10 commandments specified that petroleum should as a general rule be landed in Norway. Where oil is concerned, this occurs in two places – the Sture and Mongstad terminals in the vicinity of Bergen. Many now conceived a hope that a third could be located in Finnmark. But laying a pipeline calls for sufficient petroleum in a discovery or genuine expectations that enough reserves can be found in nearby prospects or exploration opportunities. Johan Castberg was commercially marginal in Statoil’s internal calculations. “The project team has done a good job, and it’s difficult for us,” Hans Jakob Hegge, head of operations north, said in February 2013. “It’s a very close race between a landfall and an offshore solution.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finnmark Dagblad, 8 February 2013.

A resolution came on 12 February that year, with a presentation at Veidnes in Nordkapp local authority. Oil from Johan Castberg was to be piped 280 kilometres to a storage facility at Veidnes for loading via a quay to tankers, with 50-100 calls per year. Statoil’s own figures indicated 50 jobs directly associated with the landfall, in addition to the construction phase and spin-offs. Some people were even concerned about the “massive” growth, but nevertheless took a positive view. “This will challenge the local council in terms of area planning and development, but we accept that challenge with pleasure,” said Labour mayor Kristina Hansen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nordlys, 12 February 2013.

People celebrated and rejoiced, and local paper Finnmarksposten devoted nine pages to the happy news. An upsurge in the property market was also reported, with houses being sold for six times their appraised value.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Finnmarksposten, 8 February 2013.

Pipeline and quay were priced at NOK 10 billion out of a total development cost of NOK 80 billion. “We’ve concluded that a terminal is the best solution, both financially and environmentally,” said executive vice president Øystein Michelsen at the Veidnes event.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 13 February 2013.

Renaming

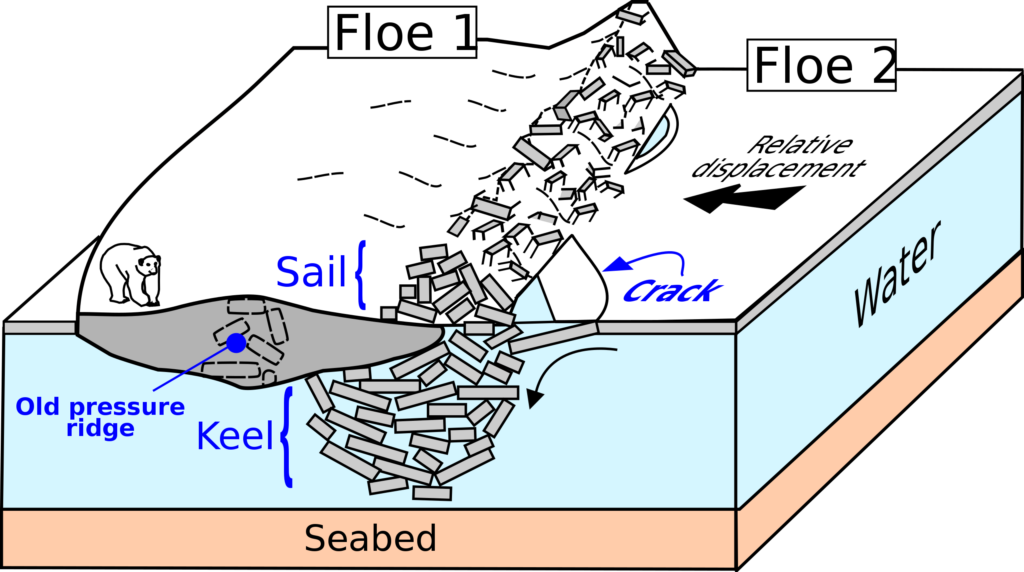

The Norwegian term “skrugard” denotes a pressure ridge created when ice floes are squeezed together and break up, while blocks of ice between them freeze wholly or partly and become compacted.

As Havis (sea ice), Drivis (drift ice), Isflak (ice floe), Skavl (snowdrift) and Kramsnø (wet snow) testify, ice and snow phenomena form the thematic basis for naming discoveries in this area. Many people found that appropriate, because it is among the northernmost parts of the NCS opened for exploration. However, not everyone agreed with these choices. Moe announced in April 2013 that he had picked “Johan Castberg” as the name for a Skrugard/Havis development. This reflected a desire to escape from the “Harry Potter and Grimms’ Fairy Tales” naming tradition, and initiated a policy where the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy opted for the names of historical Norwegians – although operators were at liberty to make proposals.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.tu.no/artikler/statoil-ville-at-dette-feltet-skulle-hete-dronning-margrethe/231193.

Johan Castberg (1862-1926) was a Radical People’s Party politician who served as minister of social affairs and is best known for the “Castberg children’s laws” – a precursor of the modern welfare state.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.norgeshistorie.no/forste-verdenskrig-og-mellomkrigstiden/1642-de-castbergske-barnelover.html.

Tax rules, uncertainty and cost rises

It became known in June 2013 that estimated costs had risen by NOK 30 billion, and the project was postponed. Another negative impact on the development was proposals to lower the level of uplift in Norway’s petroleum tax regime, which could reduce the field’s profitability. To cap it all, Statoil was pursuing a major exploration campaign to expand the resource base for a development.

The breakeven oil price for Johan Castberg was originally USD 64 per barrel, but this was now raised to USD 81 as a result of the cost increases and tax changes.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, 6 June 2013.

Statoil’s exploration campaign yielded a couple of relatively small discoveries, nowhere near the total of one billion barrels which had been muttered about. Uncertainty about the project therefore persisted.

It remained unclarified in 2016, and even greater uncertainty prevailed about a landfall. “The Castberg field is large, but not big enough on its own to bear a terminal solution,” said Statoil press spokesperson Ola Anders Skauby.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 14 January 2016. “Work is therefore continuing together with the other companies which have interests in the area to find robust solutions.”

Disappointment, final plan and approval

Statoil presented a plan for development and operation (PDO) of Johan Castberg in 2017, with the heliport and supply base located in Hammerfest and plans to place the operations organisation in Harstad. An FPSO on the field would load oil directly into shuttle tankers for shipment to market. During the consultation process on these proposals, Statoil was peppered with discontented comments from northern Norway – and Finnmark in particular – because the landfall option had been dropped. But that had no consequences for final approval of the PDO, which was given by the Storting in June 2018.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/358428f8785c4057a9cc143ed221ec75/no/pdfs/prp201720180080000dddpdfs.pdf.

The status in February 2022 is that development continues, with the FPSO hull on its way from Singapore to Norway. Plans call for the field to come on stream in 2024.