Bounded and boundless

These three arenas are naturally distributed unequally between the three main divisions of the NCS for petroleum production – the North, Norwegian and Barents Seas. But important common denominators can also be found.

North Sea – confined area, unconfined reservoirs

The possibility of petroleum deposits beneath the North Sea led to a reorientation of attitudes to international law by the Norwegian government in the early 1960s. Previously, its aim in discussions on territorial limits had been to protect the rights of Norway’s fishing industry in coastal areas. This issue was considered so important that it was worth a lengthy conflict with the British in 1911-51.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For a concise review of the maritime boundary issue from 1812 to 1951, see Berg, Roald, 2016, Norsk utanrikspolitikk etter 1814. Samlaget: 41-43. For more detailed information on the beginnings of the conflict over territorial limits and Norwegian international law specialists, see Eide, O. J., 2019, Norge i Arktis 1906-1933. Folkerettsjuristenes fellesskap, faglige legitimitet og politiske handlekraft i spørsmålene om Svalbard, sjøgrensen og Øst-Grønland. PhD thesis, University of Stavanger: 99 ff.

With a view to possible offshore petroleum production, the government declared Norwegian sovereignty over the NCS in 1963.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Vislie, Ingolf, 2017, Jens Evensen. Havet, oljen og retten, Orkana: 156 ff; Proposition no 75 (1962-63)) to the Odelsting. Treaties entered into with the UK and Denmark established the median line principle for defining their respective North Sea sectors. That meant boundaries were equidistant from each country’s coast.

It is remarkable how quickly these dividing lines were defined in the 1960s compared with the lengthy process of determining the territorial waters. A major reason was that all sides wanted to clarify these limits in order to start exploring an offshore area with manageable water depths.

The North Sea boundaries agreed at that time had consequences for several of the fields where Statoil has since been heavily involved.

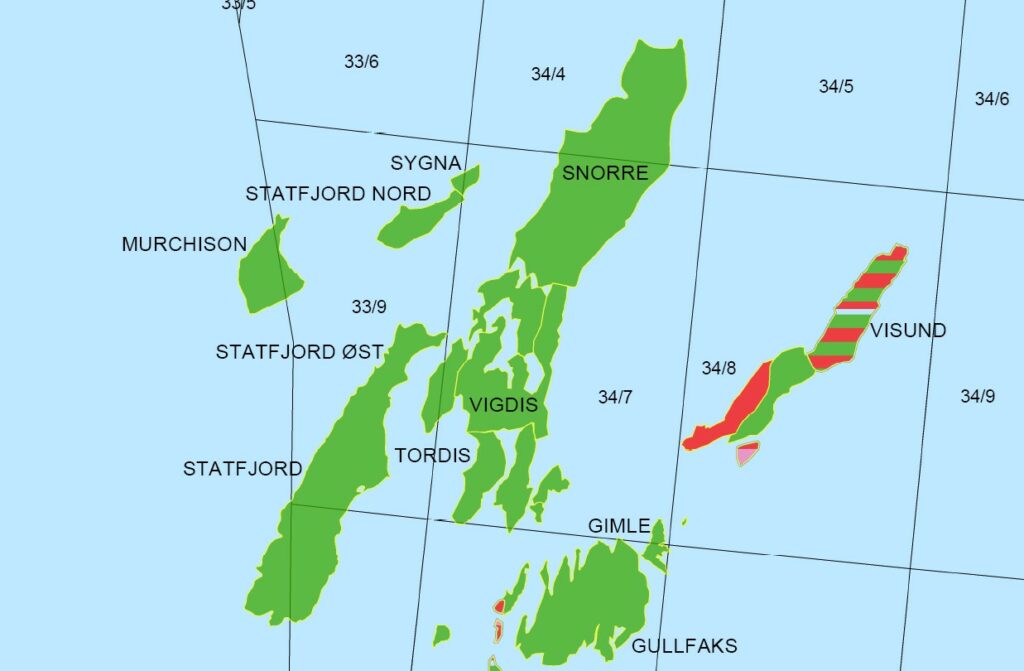

One example is the cross-boundary Statfjord field. The position of the median line between Norway and the UK means that the enormous reservoir is split between them – admittedly with more than 80 per cent on the Norwegian side. This division has led to lengthy negotiations on how production should be organised. The solution has been to place the installations in Norway’s sector, but to divide up output on the basis of detailed calculations concerning each country’s share of the reservoir. As the largest oil field in the North Sea, Statfjord has been a cornerstone of Statoil/Equinor’s finances. Small changes in determining the median line would have a significant impact here.[REMOVE]Fotnote: On challenges with the shared reservoir, see for example: Lavik, Håkon. The final redetermination, 1995–98 https://statfjord.industriminne.no/en/2019/11/11/the-final-redetermination-1995-98/, accessed 2 August 2022.

Another example of boundary challenges is Troll A, the platform which marked the depth limit for concrete installations. An important point here is the way Statoil/Equinor has been involved in a project which overcame the challenges faced in the deepest parts of the North Sea. As production operator for Troll Gas (and now for the whole field), the company demonstrated that it was possible to produce large and stable gas volumes from a fixed concrete platform in water depths beyond 300 metres.

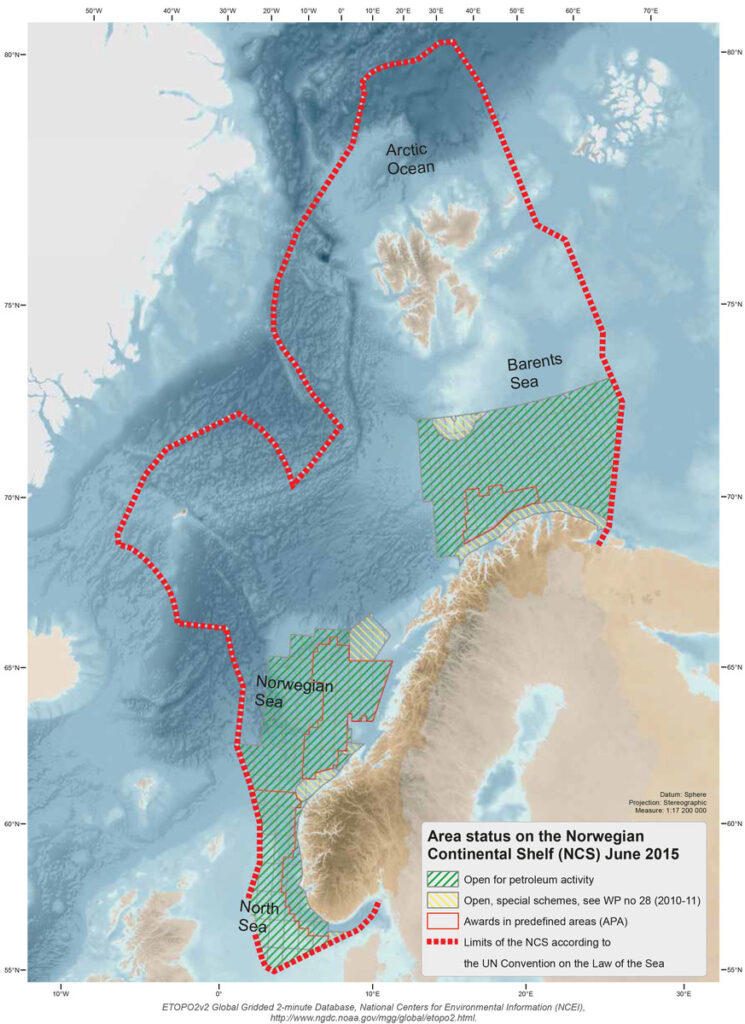

Norwegian Sea – wide zone and deep water

With effect from 1 January 1977, the Norwegian government established a 200-nautical-mile economic zone extending out from the coast. Norway’s sovereign rights here include exploiting and managing resources – such as fish or petroleum – in the sea, on the seabed and in the subsurface. Following extensive multilateral negotiations through the UN system, the arrangement was formally incorporated in the UN convention on the law of the sea in 1982. The zone was restricted in the North Sea by the median line with other states, but by and large reached its full extent in the Norwegian Sea.

Rights of the coastal state in an economic zone are closely related to its possession of a continental shelf which corresponds under international law with the extent of the zone. The UN’s commission on the limits of the continental shelf can also approve extensions to the zone on the basis of documentation submitted by the relevant state. As a result of such a process, the NCS in the Norwegian Sea extends considerably further out than its economic zone there.

International law thereby gives the country wide scope in terms of acreage for exploiting petroleum resources in the Norwegian Sea. However, the depth of its waters have made big demands on technological progress for achieving profitable recovery. The Aasta Hansteen field in 1 270 metres of water provides an example of how Equinor operates in this part of the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aasta Hansteen https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/facts/field/aasta-hansteen/, accessed 2 August 2022.

Barents Sea – Arctic isolation

The Barents Sea has long presented special challenges. First, talks on clarifying a boundary line with the Soviet Union and later Russia took a very long time. A treaty on this subject was entered into in 2010, 40 years after the first informal negotiation meeting.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ratified 2011. See 1) Delelinjeavtalen med Russland https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/utenrikssaker/folkerett/delelinjeavtalen-med-russland/id2008645/, accessed 2 August 2022. 2) The background to the treaty https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/foreign-affairs/international-law/innsikt_delelinje/treaty_background/id614274/, accessed 2 August 2022. Second, the area is a long way from export markets.

Statoil/Equinor was responsible for the first development in this part of the NCS. Given the name Snøhvit, this field lies in just over 300 metres of water.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Snøhvit https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/facts/field/snohvit/, accessed 2 August 2022. That reflects the fact that the Barents Sea, like the North Sea, is relatively shallow. Gas and condensate are produced from subsea templates, without surface installations on the field. The wellstream is piped 145 kilometres to the Hammerfest LNG plant at Melkøya. Liquefied natural gas, the main product, is loaded into specialised carriers for shipment to markets worldwide.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Unique range

The examples above illustrate the unique range of experience at the edge acquired by Equinor on the NCS – along median lines, in deep waters and far to the north. It has thereby developed profitable solutions for petroleum production which help to give it a dominant place on the NCS.

At the same time, this position confers a great responsibility for following up ambitions to be climate-neutral by 2050.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor sets ambition to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. https://www.equinor.com/news/archive/20201102-emissions, accessed 2 August 2022. Such a target can inspire innovative thinking on what types of boundaries are the most significant, and whether the boundless challenges are perhaps the most important.

arrow_backWind energy supplements gas-fired power on TampenFive decades as an oil and energy cityarrow_forward