Control of Statfjord and the key blocks

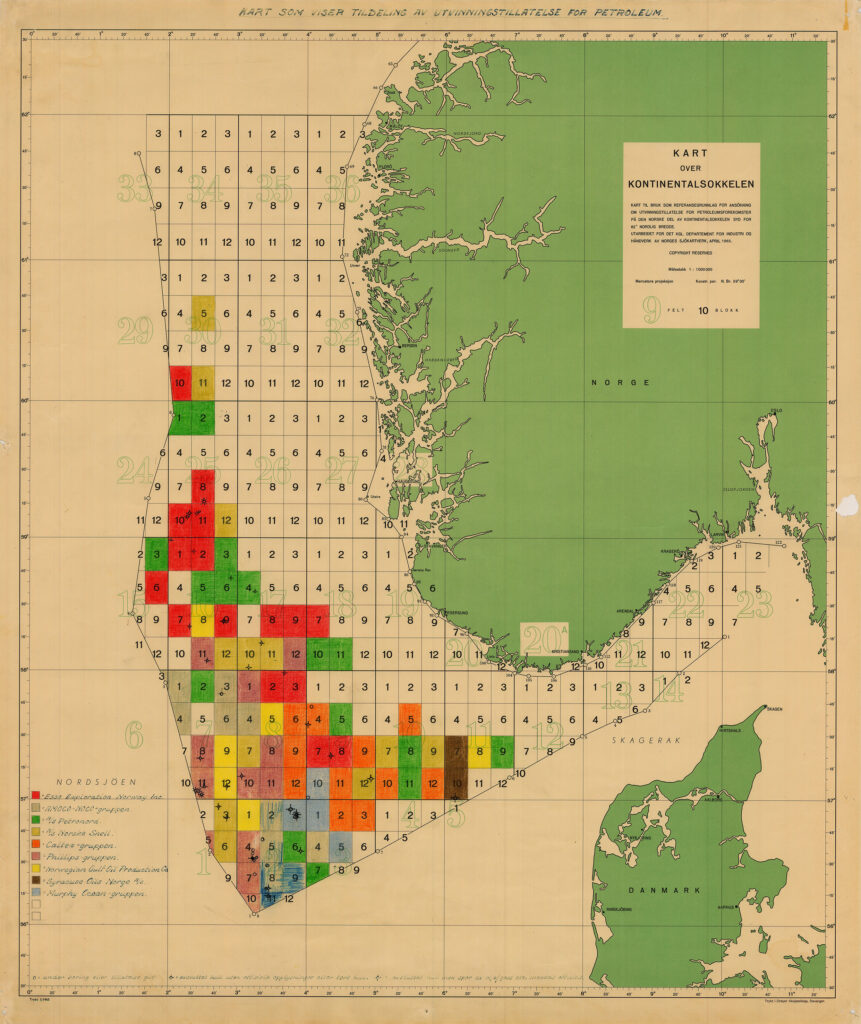

The company got off to a good start when it was awarded interests at an early stage in particularly promising acreage and in proven petroleum reserves across Norway’s North Sea sector. Ever since 1969, the government had kept hold of a number of “key” blocks where seismic surveys, relevant exploration wells and enquiries from foreign companies indicated the possible presence of resources.

These blocks were allocated in the third licensing round over several years from 1973. First up were the “Norwegian Brent blocks” – 33/9 and 33/12 – which bordered on the boundary with the UK. The fight over these had begun even before Statoil was established and while Arve Johnsen, its first CEO, was still state secretary (junior minister) at the Ministry of Industry.

Brent discovered

The issue first arose in the summer of 1971 when Shell and partner Esso made a big oil discovery in the UK sector north-west of Shetland. Named Brent, it was kept secret by the licensees for a long time – with good reason.

Since the field was close to the boundary, Shell/Esso thought it might extend into Norwegian blocks 33/9 and 33/12. They wanted to secure control of this acreage, but had to act quickly in case the information leaked out and rivals tried to get in on the act.

The two companies approached the oil office at the Ministry of Industry, and informed the Norwegian authorities at a meeting on 4 February 1972 about the Brent discovery and why they thought it extended into Norwegian waters. They told the office that they intended to apply for a licence to explore and produce the two blocks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, 1992, Fra vantro til overmot?, Norsk Oljehistorie, vol 1, Leseselskapet, Oslo: 182.

Shell/Esso maintained they were the best guarantee for Norway securing the maximum return from the resources. The relevant acreage lay in deep and stormy waters, and the two companies emphasised to the ministry that they had long experience from the international oil industry. As operators, they were therefore fully capable of handling both the water depth and the weather. As compensation for awarding the production licence, the Norwegian state would receive a 12.5 per cent royalty and 30 per cent participation through a carried interest agreement.

As defined by the Norwegian government in the early 1970s, the latter gave one of the parties – in this case the Norwegian state – the option to participate with a specified percentage in a licence on a par with the other licensees if a commercial discovery was made. The state would not pay its share of the exploration costs until this field came on stream, thereby freeing it from the financial risk.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 11 (1968-69) to the Storting, Undersøkelse og boring etter petroleumsforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel i Nordsjøen, Ministry of Industry: 6.

A formal application for a licence covering 33/9 and 33/12 – dubbed the “Norwegian Brent blocks” – was submitted to the ministry on 22 February 1972.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op.cit: 184.

Nils Gulnes, head of the oil office, consulted his colleagues – engineer Olav K Christiansen, geologist Fredrik Hagemann and legal specialist Karl-Edwin Manshaus. While the office wanted to tighten the terms a little by demanding 50 per cent state participation, it was otherwise ready to open negotiations and give Shell/Esso a production licence. In a memorandum of 3 March 1972, the minister was requested to approve a start to negotiations. Director general Knut Dæhlin at the ministry also supported the proposal for talks in a marginal note.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op.cit: 184.

Application rejected

However, the memorandum bears another marginal note. This was added by state secretary Johnsen, who had been consulted on the document before it got as far as minister Finn Lied. He disagreed strongly with its conclusions and wanted any allocation postponed. The relevant blocks were regarded as extremely attractive, and Johnsen envisioned that they could be very important in building up the state oil company he and Lied were planning.

He therefore wrote: “Conferred with Gulnes, Dæhlin, Christiansen, Hagemann, Manshaus. No supplementary award to be given. To be dealt with in connection with a general announcement.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A, 2008, Norges evige rikdom oljen, gassen og petrokronene: 117.

The Labour Party, then in office, had long been working on plans to establish a state oil company. In Johnsen’s case, that involvement began when he chaired the party’s industry committee in 1970. In a memorandum dated that December, he had outlined an undertaking with a goal and tasks covering exploration, drilling, test production, landing output, refining and marketing – in other words, a fully integrated oil company wholly owned by the Norwegian state.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A, 2008, Norges evige rikdom oljen, gassen og petrokronene: 40.

When Labour came to power in the spring of 1971, Lied had taken over the industry ministry and chosen Johnsen as his state secretary. Their political approach was marked by a desire for national management and control, including the fight for an operational oil company with strategic ownership positions which allowed the state to benefit from the resources beneath the seabed. Both Lied and Johnsen were convinced that holdings in big oil fields would be the most efficient way of ensuring the highest possible resource rent for the planned oil company and thereby for the state. Giving away attractive blocks to foreign companies without national control was undesirable, and the duo were in a position to prevent it.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, H, 2009, Til siste dråpe om oljens politiske økonomi: 106. They got their way, and the final decision went against the original wishes of the oil office and the director general.

The ministry replied to Shell/Esso by letter on 27 March 1972: “After careful consideration of the opportunities for and consequences of supplementary blocks, the Ministry of Industry has come to the conclusion that it cannot make such an allocation such a short time before the general announcement. Regretfully, your application must therefore be rejected.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op cit: 184.

So “such a short time before the general announcement” was used as the excuse for refusing the request. At that time, plans called for the long-planned third licensing round to be announced during 1972.

Awaiting a third round

After the discovery of Ekofisk became public knowledge in 1970, interest in exploring for oil on the NCS had increased markedly. The oil office was inundated with questions from the companies on when a new licencing round would be announced.

The first round on the NCS was opened in 1965, and included almost all the blocks south of the 62nd parallel (which marks the northern limit of the Norwegian North Sea). Twenty-two licences embracing 78 blocks were then awarded. Covering a more limited area, the second round in 1969 aimed to provide certain blocks to supplement acreage already handed out in the first allocations.

The ministry announced in 1971 that a third round was imminent, once again involving supplementary awards to licensees who had run out of work in order to dissuade foreign companies from abandoning the NCS. But those wanting to extend exploration into adjacent blocks could also be given awards.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 76 (1970-71) to the Storting, Undersøkelse etter og utvinning av undersjøiske naturforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel m.m, Ministry of Industry. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1970-71&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL418. That autumn, the companies were urged to submit their prioritised applications.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op cit: 302. Eight responded – and they proved to have targeted well. Statfjord, Gullfaks, Snorre and Sleipner could all have gone to foreign operators had the plans been pursued.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op cit: 182. But the supplementary awards were cancelled, with no action taken on the applications. The authorities nevertheless acquired a good insight into company preferences.

Several considerations prompted a postponement of the round. Overall, however, a key factor was a shift in Norwegian oil policy towards greater national management and control as well as bigger state involvement.

State participation

Ekofisk had opened the eyes of Norwegian politicians. Now that the presence of oil on the NCS was proven, calls began to be made for these resources to serve national purposes. The second round had aimed to offer supplementary blocks to existing licences. At that point, in 1969, drilling results on the NCS had been disappointing, and the government feared that a number of oil companies would withdraw from Norway without the opportunity to explore more acreage. Further investigation of the NCS was something the government wanted, and that called for foreign capital and expertise. This gave the international companies strong cards in the negotiations and Norwegian oil policy was largely tailored to their demands.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Wentzel, T, 2008, Fra forsiktighet til fornorsking av oljevirksomheten. En studie av konsesjonstildelingene mellom 1965-1985: 34.

Report no 11 (1968-69) to the Storting, published in connection with the second round, raised the question of state ownership as a possibility but without making a direct demand for such participation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 11 (1968-69) to the Storting, Undersøkelse og boring etter petroleumsforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel i Nordsjøen, Ministry of Industry: 6. On the other hand, it was resolved that the oil office should raise the issue with the individual licensees and achieve state participation through negotiation. That was done, with involvement secured through two types of agreement – carried interest (see above) and net profit.

The latter gave the state, in addition to the fixed statutory taxes and fees, a certain percentage of the net profit earned by the licensees. Such agreements gave the government no influence on operations, and cannot therefore be characterised as state participation in the strict sense.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 76 (1970-71) to the Storting, Undersøkelse etter og utvinning av undersjøiske naturforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel m.m, Ministry of Industry: 3. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1970-71&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL418.

Key blocks

Control over key and boundary blocks was to be next step towards increased national management and control. The key block concept was employed as early as Report no 95 (1969-70) to the Storting from the non-socialist Borten government. It referred to geologically interesting areas held back because they bordered on areas where discoveries had either been made or were highly likely.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 95 (1969-70) to the Storting, Undersøkelse etter og utvinning av undersjøiske naturforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel m. m, Ministry of Industry: 14. With Ekofisk discovered, the ministry could reasonably expect rapid progress on the NCS. Report no 95 accordingly promised a supplementary White Paper but, before this reached the Storting, the Borten government and industry minister Sverre Walter Rostoft resigned. Trygve Bratteli and Labour took over on 17 March 1971.

Lied was accordingly the minister responsible for presenting Report no 76 (1970-71) to the Storting a month after the change of government.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 76 (1970-71) to the Storting, Undersøkelse etter og utvinning av undersjøiske naturforekomster på den norske kontinentalsokkel m.m, Ministry of Industry. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1970-71&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL418.

This White Paper did not deviate much from the one presented the year before, but nevertheless contained some important changes. It also attracted considerably greater interest. The most important adjustment was a decision by the ministry that the retained key blocks specified earlier should by and large be allocated to a state-owned oil company. Since this had yet to be established, no blocks would be awarded until it was in place. The upshot was a further postponement.

On 14 June 1972, the Storting unanimously voted to establish Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s, and the third licensing-round process could thereby resume.

Soon afterwards, on 20 June 1972, prime minister Bratteli held a press conference where he reported on plans to announce a number of blocks across Norway’s whole North Sea sector. However, the area between the 59th and 62nd parallels – from Stavanger northwards – would be given priority.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Oljeaktiviteten trekker nordover”, 21 June 1972. This reflected a government desire to learn more about conditions further north, since it felt that a good overview of geology in the southernmost part of the NCS had already been obtained.

Bratteli made it clear that the government would allocate a relatively limited number of blocks, and that these would only lie south of the 59th parallel in special cases. State participation on carried interest terms would be demanded with all acreage to be awarded.

Under no circumstance would production licences be given for the key blocks which the government had reserved, and which were widely distributed both geologically and geographically. According to the prime minister, these were not necessarily the best blocks but their geographical spread meant the government would always have one close to any new discovery.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Oljeaktiviteten trekker nordover”, 21 June 1972. From a negotiating perspective, the government now occupied a more comfortable position than in earlier licensing rounds. After Ekofisk, the oil industry on the NCS was in a revitalised and optimistic mood.

Under the Labour government, the industry ministry worked towards announcing a third round on 15 October 1972. But the Bratteli administration had to resign before that date, forcing a fresh postponement.

The dominant political discussion that summer had not been about oil policy or licensing, but possible Norwegian membership of the European Community (now the EU). On 25 September 1972, Norwegians voted in a referendum on EC membership after the country’s largest and bitterest controversy since 1945. Both sides maintained that the consequences for Norway would be disastrous if the other won.

This battle changed Norway’s political landscape, and demands for national self-determination – including over the oil – were strengthened. Norwegian resources were to be kept under domestic control. That must be seen as a gift to the newly created state oil company. The level of engagement with the EC issue had been very high among both politicians and ordinary voters, and it succeeded in felling two governments. Per Borten had dissolved his non-socialist coalition government of the Centre, Christian Democrat, Conservative and Liberal parties in March 1971 over leaks and a collapse in collaboration, and Labour took over.

That party’s leadership was committed to EC membership, and Bratteli proclaimed before the referendum that a Labour voter should vote “yes” to joining Europe. In August, he made the referendum a vote of confidence in his government by stating that it would resign if a majority rejected membership.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bratteli, T, “Speech at an open meeting after a Cabinet meeting on 23 August 1970, Gjøvik”, in Bratteli, T, Finne, H, Auensen, E, Graff, F and Engstad, P, 1985, Trygve Bratteli har ordet: Utvalg av taler, Tiden, Oslo: 107.

The result went against the government, with 53.5 per cent of voters rejecting EC membership, and it had to leave office.

Christian Democrat leader Lars Korvald was given the task of forming a minority coalition of parties supporting the “no” vote, which also included the Centre and Liberal parties. This group had only 47 of the 150 members of the Storting, and ranked as the government with the weakest parliamentary mandate since 1945.[REMOVE]Fotnote: It held that position until Erna Solberg’s government in 2020.

Where oil policy and Statoil were concerned, the change of government meant further delays in announcing new blocks on the NCS. Progress quite simply ceased.

In parallel with the political drama which played out in Norway that autumn, Shell/Esso went public with Brent. Studies made it clear that this was the biggest discovery so far in the North Sea basin. And parts of it could belong to Norway. The revelation of the giant find did not make the nearby Norwegian blocks any less attractive.

It was now a matter of urgency for the government to speed up the award of this acreage. In early December, the government resolved that an exception could be made to the general rule that production licences were awarded after announcing a licensing round. The ministry could then accept applications and make an award without a round being announced.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Section 12 of the royal decree of 8 December 1972 relating to exploration for and exploitation of petroleum in the seabed and substrata on the NCS: “Prior to granting production licences, the ministry shall make a public announcement as provided in section 13 hereof, such announcement shall specify the areas to which applications for production licences can be made. The ministry may, under special circumstances, accept an application for, and grant a production licence without such prior announcement being made”.

New blocks would nevertheless be announced immediately after New Year, Korvald said. Interest shot sky-high, and the oil office now received enquiries from not only oil companies but also embassies, newspapers and journalists who wanted to know what this meant.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T, Nerheim, G and the Norwegian Petroleum Society, op.cit: 302.

Shell/Esso eagerly took advantage of this opportunity to secure the “Brent” blocks outside a regular round, and once again contacted the oil office. They could now point to specific production plans for the Brent field in UK block 211/29.

In early March, the government said that it would consider this application without waiting for the next formal round. If Shell/Esso brought the British field on stream before the Norwegians had clarified whether it extended into their sector, the prospect existed that possible oil belonging to Norway might be produced from the British side. In other words, clarifying any such extension was a matter of urgency so that possible negotiations over a division of any production could begin.

What Statoil wanted

Matters were also starting to get urgent for the new state oil company if it wanted to secure control of Norway’s “Brent” blocks, which was a key goal. Statoil was still small, with only 14 employees and little experience. It nevertheless launched a vigorous offensive.

Johnsen, who had taken over as CEO on 1 December 1972, would have preferred his company to acquire production licences on its own – particularly for blocks 33/7 and 33/12. He failed to win the board’s agreement for this, but its support for a rapid build-up into an operational oil company was unquestionable.

At a board meeting on 9 March 1973, Statoil’s attitude to the Norwegian “Brent” blocks was discussed. The government wanted to move fast in clarifying their utilisation, given developments on the UK side. It feared substantial losses for Norway if its oil was drawn off by the British licensees. Statoil’s board resolved to take the initiative and to be prepared to take the step towards an operative company.

The most effective way the state could secure the resource rent was to hold interests in big oil fields – either directly or through Statoil. That now applied to the two blocks directly opposite Brent. The board outlined three scenarios in which Statoil was a key player:

- Shell/Esso, as Brent partners on the UK side, secured the production licence with Statoil as a 50 per cent partner

- the state oil company received the licence alone

- a sustainable Norwegian constellation was created, with Statoil holding 50 or 51 per cent while Norsk Hydro – part state-owned – and wholly private Saga Petroleum shared the remainder.

As mentioned, Johnsen supported option 2, but the board concluded that the company should pursue the third option. On its own, Statoil would not be able to manage an operator role as early as 1973.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board documents, digital archive. The challenge was the time aspect, with the government keen to get going fast with exploration and possible development.

Ideological conflict

The government and the ministry were concerned about the big financial burden which would fall on the state if its young oil company was allocated the block along. Questions were also raised about its ability to take on such a task. Creating a solo Norwegian grouping also had its weaknesses. The government feared that this option would not get moving quickly enough, with the ministry maintaining that exploration needed to begin as early as the summer of 1973.

A clash also began to develop between the minority government and the Conservatives on one hand and Labour plus Statoil on the other. Although the latter had been established by a unanimous Storting, it remained unclear how large the company should become, how much power it was to be given, and how the Storting should control it.

The non-socialists maintained that the state company was still small and inexperienced, and that the tasks it could take on were limited. But Statoil received massive support from Labour. Unlike the year before, however, political interest in oil policy had now blossomed. Debates had become more heated and these issues were red-hot. The two sides were strongly entrenched, with Labour brutally critical of the government’s approach – particularly over the issues affecting Statoil.

A sharp exchange occurred in the Storting’s question time on 21 March 1973 between Ingvald Ulveseth, the Labour chair of the standing committee on industry, and Ola Skjåk Bræk, the Christian Democrat who was industry minister.

Ulveseth had heard through the press that the government would not necessarily reserve the “Brent” blocks for Statoil, and that the ministry might licence this acreage behind the scenes to private companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting question time 21 March 1973, item 3: 2228/Storting proceedings for the 117 regular Storting 1972-73: 2222-2225, https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1972-73&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL411&pgid=b_0884. Report no 51 (1972-73) to the Storting, approved by the Council of State on 6 March, noted that the ministry had received an application from Shell/Esso for a production licence covering blocks 33/9 and 33/12, and that it would consider this in relation to section 12 of the royal decree of 8 December 1972 (see note 21).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report 51 (1972-73) to the Storting, Ilandføring av petroleum fra Ekofisk-området: 39, Ministry of Industry. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1972-73&paid=3&wid=c&psid=DIVL460.

Was it the case that the government would no longer reserve these blocks for the state oil company being built up, Ulveseth asked. Was it the case that foreign companies would be given a free hand? At the same time, he expressed his conviction that Statoil would be able to conduct exploration drilling on the acreage in question together, for example, with Hydro and Saga.

Ulveseth’s point was that the blocks should not be handed to Shell/Esso, but be placed in the same category as the key blocks and transferred to Statoil in line with the view of the majority on the industry committee. The latter had made it clear that key and boundary blocks should be reserved for the state’s own oil company. It was Ulveseth’s understanding that the Storting had already decided that the boundary blocks should go to Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting question time 21 March 1973, op.cit: 2228.

Skjåk Bræk could confirm that the Shell/Esso application was under consideration, and took the view that this pair were among the few companies with sufficient technical expertise, experience and resources to drill under such difficult conditions. But he was not equally convinced of Statoil’s ability to pursue such operations. He argued that the company was being built up and lacked any practical experience in the area. It had already been given a lot to do, including pipelines and not least rights to state participation in 31 blocks negotiated by the government and transferred to it. Moreover, a financial risk was associated with exploration activity which would cost the state dear if nothing were found. Regardless of the outcome, the government would nevertheless ensure a high level of state involvement.

Ulveseth was not satisfied with this answer, and asked for the issue to be brought before the Storting. In his view, this was where the decision should be taken.

Storting settles the matter

The industry committee was thereby requested to prepare a recommendation for the full house. Presented in April 1973, this proposed giving Statoil wide powers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 279 (1972-73) to the Storting from the industry committee on the exercise of the state option to participate in production licence no 024 for petroleum (Frigg field), and the transfer to Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s of agreements on state participation in production licences, etc (proposition no 78 to the Storting). Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1972-73&paid=6&wid=a&psid=DIVL2086.

Future state participation should be transferred to it, and the company would participate in each production licence on an equal footing with the other licensees. It would take part actively and have direct influence on the management of operations in all phases.

The committee majority also proposed that awards should be confined for the moment to the key and boundary blocks and that these were reserved for Statoil.

A minority consisting of two Conservatives disagreed. They maintained that no regulations existed for exerting authority over the state company, and feared that the Storting would lose its control.

Skjåk Bræk and Dæhlin expressed their dissatisfaction in a letter to the industry committee, where they pointed out that reserving the key and boundary acreage for the state oil company would amount to no less than 100 blocks. That would give it far too much power over oil policy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting debate. Accessed at https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1972-73&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL411&pgid=c_0209.

A fresh debate was staged in the Storting on 23 May 1973, with new conflicts looming. Concerns were being expressed by a growing number of non-socialist representatives at a trend towards giving Statoil ever greater responsibility for national resources without the Storting acquiring corresponding influence over the company.

Conservative Olaf Knudson described Statoil as a “cuckoo in the nest” – growing steadily bigger at the expense of the parents feeding it. He was fearful of a company which would control significant proportions of the country’s oil revenues without the Storting in control.

The letter from the minister was sharply criticised in the Storting but, as the lowest common denominator, agreement was reached that the announcement of blocks – particularly the key and boundary ones – would be made in consultation with Statoil.

Where the “Brent” blocks were concerned, however, Skjåk Bræk made his position clear. They had been announced, and with a very short deadline, in accordance with the exception provided under section 12 of the royal decree. Negotiations were already under way with about 20 companies. The announcement of what were known at the time as the “golden blocks” had been made on the assumption that they would be open to competition rather than being reserved for Statoil.

The industry committee’s recommendation was approved against the votes of 23 of the 29 Conservative representatives. This decision indicated a clear change of course in licensing policy towards Norwegianisation and a clear prioritisation of the state’s own oil company.

arrow_backWinning agreement on a state oil companyDen norske stats oljeselskap is establishedarrow_forward