Five decades as an oil and energy city

From being a relatively poor industrial town, Stavanger has become the centre of a major urban region which ranks as Norway’s third largest – bigger than Trondheim.

Being chosen to host two key state institutions had spin-offs whose importance can hardly be over-stated.

Statoil, which started out with an empty cigar box to hold its petty cash, has become Norway’s most valuable company and is currently priced at more than NOK 700 billion. It was partly privatised and listed on the stock market in 2001 and changed its name to Equinor in 2018.

The NPD was divided in 2004 when the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA) became a separate agency responsible for ensuring that the oil industry complies with legal and regulatory requirements and provides safe jobs.

Unique industry history

Stavanger was not selected as the location for Statoil and the NPD by chance. The town had already become a base for offshore exploration, and optimism prevailed after the discovery of Ekofisk in 1969. International oil companies and contractors were moving in, and the oil industry became visible in the urban scene.

As more discoveries were made and slated for development – first Frigg, then Statfjord, Valhall and others – activity on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) increased. Suppliers in the Stavanger area more than filled their order books. Local industry delivered notable results.

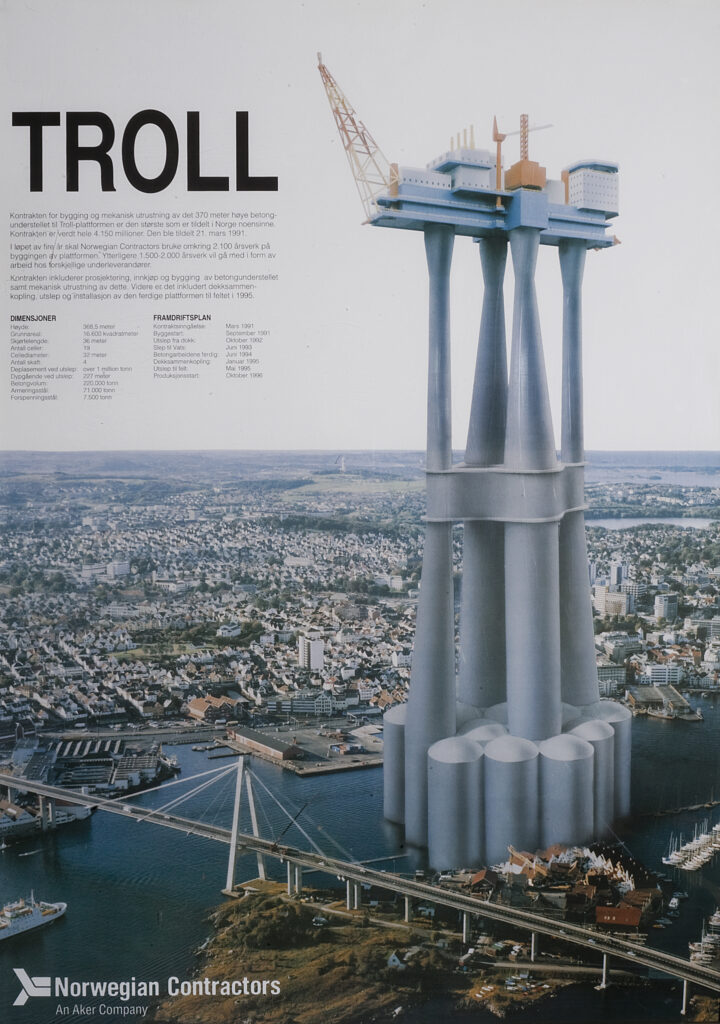

Following the unique Ekofisk concrete oil storage tank, the Norwegian Contractors consortium built 16 of its Condeep gravity base structures (GBSs) in concrete to support offshore platforms. The tallest was Troll A, which ranks as the world highest moveable construction. Stavanger’s Rosenberg Mek Verksted yard, which had previously built oil tankers and gas carriers, assembled the steel topsides for a number of these platforms. Between them, these two companies created thousands of jobs – including many for guest workers.

The Condeep adventure lasted a little more than 20 years. Troll A was put in position on 17 May 1995 as the last of these structures. Limits existed for how tall they could become. While Norwegian Contractors was wound up, Rosenberg secured other work – including the fabrication of subsea templates and production ships.

Subsea technology was in the process of outcompeting the concrete giants on the NCS. And yards like Rosenberg were able to adapt to new types of assignment.

When the NCS above the 62nd parallel – the northern limit of the North Sea – was opened for oil exploration in 1980, offshore operations really spread up the coast and Stavanger was no longer Norway’s only oil town. Bergen, Haugesund, Kristiansund, Florø, Harstad, Hammerfest, Kongsberg, Trondheim, Kristiansand and Oslo all fell more or less into this category. But the original oil capital retained that title.

Education and research for the future

Right from the very start in 1966, foreign oil families arriving in Stavanger needed educational provision for their children. International schools were established – American, French and British – which became cornerstones in the expatriate oil community.

The educational and research institutions which have grown up in Stavanger over the past 50 years have nevertheless become the most important foundations for learning in the city. Established in 1969, the Rogaland Regional College quickly put petroleum studies in place to educate much-needed engineers. This developed by 2005 into the University of Stavanger (UiS), which represents an important workplace with 2 000 staff and 12 600 students in 2022. Its motto is to challenge the well-known and investigate the unknown.

Created in 1973, Rogaland Research secured much of its work from the petroleum sector. It became the International Research Institute of Stavanger (Iris) in 2006 and has since merged into the Norwegian Research Centre (Norce) as part of a wider R&D fellowship in southern and western Norway.

Research is also an important activity at the city hospital, which has become the University Hospital of Stavanger. The centre of gravity for research in the region is the Ullandhaug district, and that became even clearer when the hospital also moved there.

Regional centre

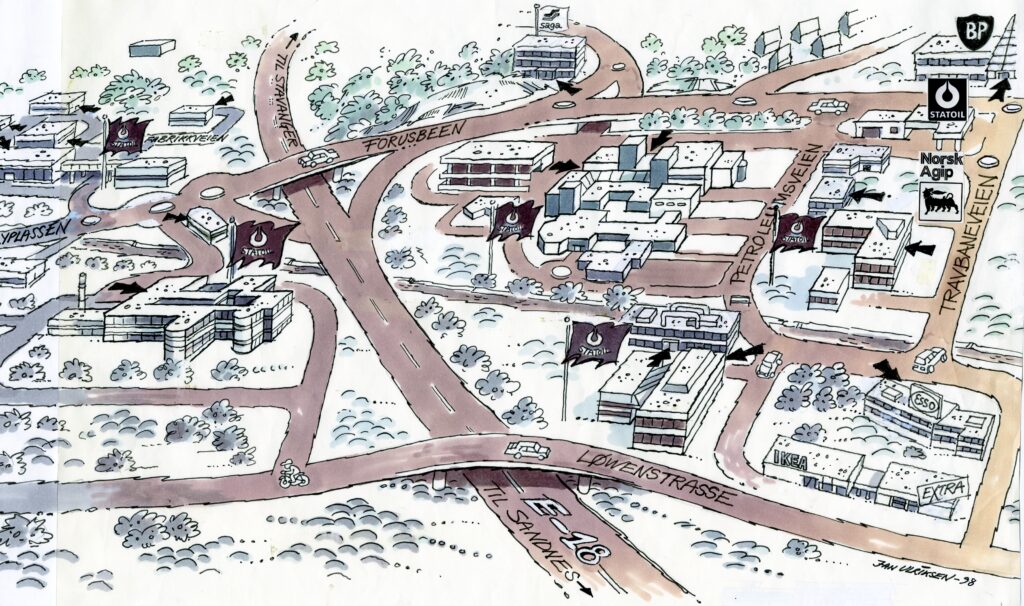

Together with the local oil bases, the Forus district has become the commercial engine in the Stavanger region. The Forus Business Park was established at an early date as an intermunicipal collaboration with the neighbouring Sandnes and Sola local authorities.

Statoil moved its head office to Forusbeen 50 in the late 1970s, encouraging a number of other oil companies to locate there. They wanted to be close to the state oil company and the NPD.

The supplier industry was also strongly represented in what deserves to be called an oil industry cluster. Companies at Forus account for a large share of total value creation in Norway’s petroleum sector. A total of 3 000 businesses in various sectors are established in the area, employing some 45 000 people.

Several other government institutions have later been located in Stavanger. The most significant of these is the Petoro company at Bjergsted near the city centre. Since 2002, it has administered the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI) on the NCS and alone delivered NOK 186 billion to the Treasury in 2021.

Restructuring and green shift

Being an oil city nevertheless has some disadvantages. Business activity is very dependent on petroleum prices, which move both up and down. The four-year downturn which began in 2014 was a lesson in that respect. A number of the international oil companies opted to sell out of the NCS during this period and thereby left Stavanger. Prices in the supplier industry came under heavy pressure, and prompted a restructuring.

Another factor which contributed to change was the Paris agreement of 2015, which adopted the 2°C target. This means that Norway and many other countries have undertaken to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in a bid to keep the rise in planetary temperature below that ceiling.

The shift to greener commerce is now also materialising in Stavanger. A climate investment fund called Nysnø was established in 2017 and had built up NOK 2.4 billion in capital by 2021 with the aid of government grants for making long-term investments in companies which can help to reduce GHG emissions.

Oil companies are turning themselves into energy enterprises, with Statoil changing its name to Equinor in 2018 to signal values such as justice, equality and balance as well as its Norwegian origin. Equinor’s strategy identifies climate change as today’s biggest challenge, and it is making a relatively substantial commitment to offshore wind power – primarily in the UK, but also in Poland and the USA. The first floating wave power project on the NCS is under construction in the Tampen area of the North Sea to supply local oil platforms with green electricity.

Mayor Kari Nessa Nordtun preferred in 2020 to describe Stavanger as an “energy capital” rather than an oil centre. She had several good grounds for doing so.

Local energy company Lyse supplies clean and renewable hydropower and is making a big contribution to digitalising society. Rosenberg aims to convert to manufacturing equipment for offshore wind turbines. Changes are being made at the university, in collaboration with Lyse, to educate the young people of the future in the new industries emerging from the continued electrification of society – battery factories, hydrogen production, seabed mineral recovery and carbon injection. All this requires new expertise.

Local politicians are gearing up again to show that Stavanger and its surrounding Rogaland County is well placed to take a lead in the green shift. This offers many parallels with the efforts in 1971-72 to become the oil capital. Lessons from that earlier period include the importance of being early off the mark and of reaching cross-political agreement on achieving the transition which many people want to see. Although Norway is still, for good reasons, producing oil and gas at full stretch, Stavanger has already begun the green shift.