Arve Johnsen’s departure

Mongstad was an anonymous little community on the Fens Fjord before massive oil developments began in the area. The project formed part of Arve Johnsen’s plans to make Statoil a fully integrated oil company. That involves being involved along the whole value chain from offshore exploration and development to refining and service station operation.

The refinery at Mongstad became operational in 1975, and was owned 70-30 by Statoil/Norol and Norsk Hydro. When the question of expanding and upgrading the facility arose a few years later, Hydro no longer wanted to participate and eventually pulled out. That left Statoil alone with the project – and the overruns.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 16 (1987-88) to the Storting, Kostnadsoverskridelsene ved utbyggingen av raffineriet og råoljeterminalen på Mongstad, appendix on “Redegjørelse for utviklingen i investeringsestimatene for Mongstadprosjektene. Oktober 1987”, Ministry of Petroleum and Energy: 55-56.

Cost increases

The figures which formed the basis for the 1984 decision by the Storting (parliament) to approve Statoil’s Mongstad plans have been described as “far too optimistic”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, Johannes, 1999, På tidens skanser, Tapir: 215. Expanding the refinery was assumed to cost just over NOK 4 billion in 1983 value.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 16, op.cit: 5-6. The 1987 “section 10 plan”, which fulfilled Statoil’s duty to give the Storting an annual briefing on its plans, put the bill at NOK 5.8 billion, while a new crude oil terminal was costed at NOK 1 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk Oljehistorie, Norwegian Petroleum Society, Leseselskapet: 246. In April 1987, the board was also briefed that tenders for the electrical instrumentation at Mongstad were “substantially over budget”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Statoil, 30 April 1987, item 4/87-2 (Source: SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Aba/L0003: Styremøteprotokoller, 27.08.1985 til 28/29.06.1990. Dokumentliste Styret og Representantskapet 1974 til 1979, 1974-1990).

The two estimates mentioned above were adjusted upwards in June 1987 to NOK 7.6 billion and NOK 1.3 billion respectively. At the end of September, the figures had crept up to NOK 9.2 billion and NOK 1.4 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Statoil, 24 September 1987, item 11/87-1 (Source: SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Aba/L0003: Styremøteprotokoller, 27.08.1985 til 28/29.06.1990. Dokumentliste Styret og Representantskapet 1974 til 1979, 1974-1990). Soon afterwards, the board requested a detailed management report on the project.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Statoil, 30 September 1987, item 11/87-1 (Source: SAST, Pa 1339 – Statoil ASA, A/Ab/Aba/L0003: Styremøteprotokoller, 27.08.1985 til 28/29.06.1990. Dokumentliste Styret og Representantskapet 1974 til 1979, 1974-1990).

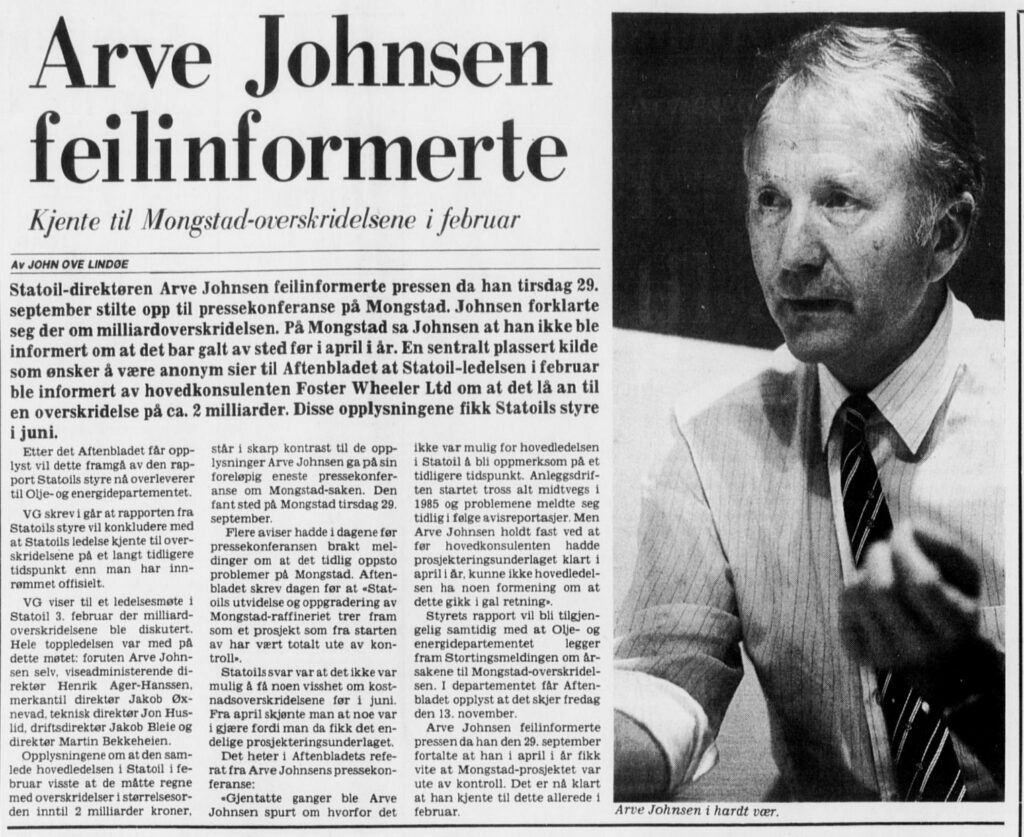

By the end of September 1987, the overruns had also reached the newspaper front pages.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See, for example: Stavanger Aftenblad, 28 September 1987, “Mongstad aldri under kontroll” (front page) and Stavanger Aftenblad, 30 September 1987, “Informasjonskaos i Mongstad-saken” (front page). Media attention persisted during the autumn, and related among other considerations to when Johnsen had first learnt about the cost increases.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See, for example, Lindøe, John Ove, “Arve Johnsen feilinformerte. Kjente til Mongstad-overskridelsene i februar” , 30 October 1987, Stavanger Aftenblad: 4.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy began working on a report to the Storting on the Mongstad overruns. Appended to this White Paper was a report from the Storting board, which painted a complex picture of what had gone wrong. It described the overruns as “very serious” and said that “the degree of difficulty in the project was underestimated as early as the initial studies by everyone involved in the many reports and studies produced”. Furthermore, the board found that “routines between the CEO and the board have proved inadequate in the Mongstad case”. It noted that the CEO would “take note of the criticism”, and that the board would “seek to identify a more suitable form of communication and contact between the company’s management and the board and owner …”. However, its conclusion did not include a demand for Johnsen’s resignation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For the full text, see Report no 16 (1987-88) to the Storting, Kostnadsoverskridelsene ved utbyggingen av raffineriet og råoljeterminalen på Mongstad, appendix on “Redegjørelse for utviklingen i investeringsestimatene for Mongstadprosjektene. Oktober 1987”, Ministry of Petroleum and Energy: 73-74.

Conservative Storting member Per Kristian Foss called on 12 November for Johnsen to go. But Stavanger’s Conservative mayor Arne Rettedal demonstrated “once again that he contradicts the party’s leaders” by supporting the Statoil CEO. He justified this on the grounds that Johnsen’s possible departure “could mean that the company loses its dynamism and harms [its] operations abroad”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nedrebø, Rune, “Arne Rettedal: Ikke rør Arve Johnsen” , 13 November 1987, Stavanger Aftenblad: 4. See also Hatløy, Odd, “Jeg er ikke Høyres opprører”, 14 November 1987, Stavanger Aftenblad: 4. At the same time, Johnsen had been undoubtedly been a good man for Rettedal in regional policy terms during the years he had served at Statoil. So the mayor was not alone in his view – at least not in his own county.

Despite active supporters, however, little doubt prevailed about the big picture which was emerging – dark clouds had gathered over both Johnsen and the board.

When the Auditor-General levelled sharp criticism at board and management as well as the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and its minister, the position became even more strained.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 17 November 1987, “Riksrevisjonen med Mongstad-refs”: 4.

Decision time

The first step towards a decision on Johnsen and the board’s future took place at a board meeting on 19 November 1987. At the end of the session, deputy chair Vidkunn Hveding moved that Johnsen should go. The majority of the directors did not support this. On the following day, Hveding resigned from the board in the company of two other directors. Chair Inge Johansen and two more directors submitted their resignations on the same day.

The opposition whetted their knives. Conservative Party chair Rolf Presthus characterised the affair as “the biggest industrial scandal Norway has experienced”. He also announced that Labour prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland’s job would be hanging by a thread unless she fired either petroleum and energy minister Arne Øien or Johnsen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 20 November 1987, “Mistilliten henger fortsatt i luften. Mongstad-saken tilspisser seg ytterligere”: 4.

On 22 November, Johnsen offered his resignation to Øien.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For Johnsen’s own version of the board meeting and its outcome, see Johnsen, Arve, 1990, Statoil-år. Gjennombrudd og vekst 1978-1987, Gyldendal: 288-290. See otherwise, for example, Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 251-252. He received considerable support from the unions – and it was emphasised that he had not resigned.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Jølbo, Ove, “Mobiliserer med brev – møter Johnsen og Øien. Uvisshetens sky driver i Statoil-korridorene” , 24 November 1987, Stavanger Aftenblad: 5. In practice, however, his fate had been sealed by the reverberations from the earlier board meeting.

Where Hveding was concerned, this marked the end of a long relationship with Statoil. He had left the company’s board in 1974 in connection with Jens Christian Hauge’s departure as chair. In the meantime, Hveding had been petroleum and energy minister in the 1981-83 Conservative government before again becoming a Statoil director. His resignation in the autumn of 1987 played its part in the departure of both chair and CEO.

Inheritance

In many ways, Johnsen and Hveding personified the continuity in the left-right fight over Statoil’s size and power during many of the first 15 years of the company’s history. Both were now out of it for good.

If the Mongstad affair had clarified one thing, it was the CEO’s responsibility for cost overruns. Johnsen’s heir was also to experience that.

arrow_backA tasty Danish – but not lastingHarald Norvik – a purposeful leaderarrow_forward