Victory over Mongstad expansion

“The oil refinery at Mongstad was beset by conflict right up until Hydro sold out in 1987,” one assessment concludes.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johannessen, F E, Rønning, Asle and Sandvik, Pål Thonstad, 2005, Nasjonal kontroll og industriell fornyelse: Hydro 1945-1977: vol B 2: 468, Pax: 344. Lasting roughly a decade, the collaboration between Statoil and Hydro over this facility was afflicted by disagreement over whether it should be expanded and modernised. For financial and other reasons, the Hydro was sceptical to this proposal. Statoil, on the other hand, believed that the market was good enough and that the refinery needed to be developed to avoid being left behind.

To refine or not to refine – that was the question

During the early 1970s, foreign oil companies – with Phillips Petroleum in the lead – argued that Norway would be better served economically by exporting crude rather than refined products. But the Storting adopted a policy statement in 1971 known as the “10 oil commandments”. One of these stated that “Petroleum from the NCS must as a general rule be landed in Norway”. The underlying view was that oil refining and associated activities would create domestic jobs – and thereby tax revenues. In other words, the Storting did not wholly accept the arguments of the international oil companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, 1996, En gassnasjon blir til, vol 2, Norsk oljehistorie, Leseselskapet: 170; https://www.norgeshistorie.no/kilder/oljealder-og-overflod/K1905-de-ti-oljebud.html, accessed 26 January 2021.

How far it made sense to refine or export crude oil was a question with no easy solution. Forecasts and assessments existed, but it was difficult even a decade later to come up with an unambiguous answer.

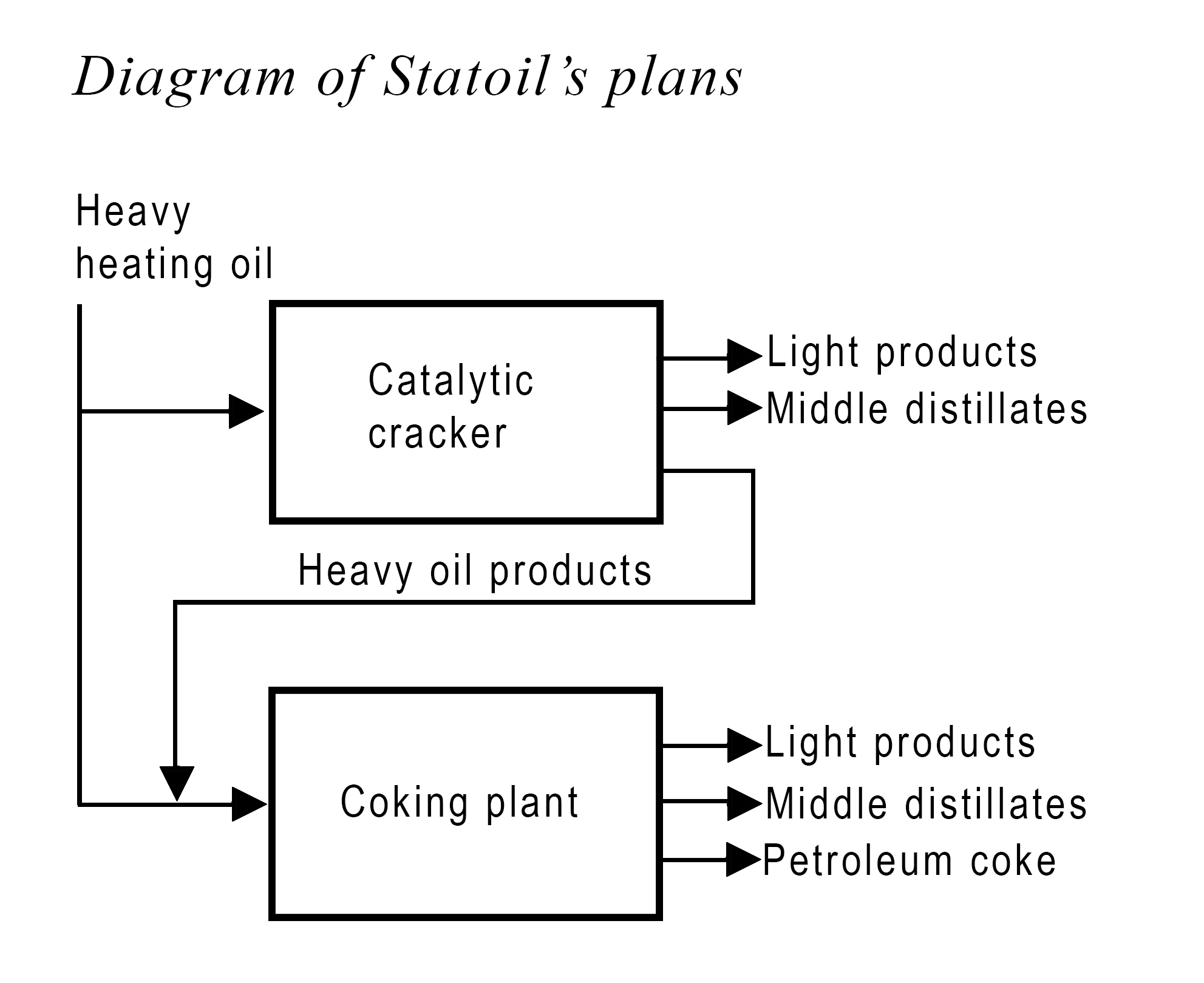

What was certain, however, was that western Europe’s refinery industry was changing in the 1980s because demand for heavy refined products such as heating oil had begun to fall. Some nations were keen to reduce their dependence on oil, industries were in decline and a number of countries wanted to convert to cheaper and more predictable energy bearers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98 (1983-84) to the Storting, Om moderniseringa av Mongstad-raffineriet: 11, https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL288&pgid=b_0417. One example is Sweden, which turned to nuclear power as a replacement for oil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 111 (1984-85) to the Storting, Om Statoil kjøp av Esso Invest AB i Sverige: 10, https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1984-85&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL920. And the latter was also on the way out in Norway.

On the other hand, demand was expected to grow for such light oil products as diesel oil and petrol. No real alternatives to these existed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 8 The outcome of these changes was that existing refineries were unable to exploit their full capacity because they were built to supply products no longer in demand. Costs related to heating, flaring[REMOVE]Fotnote: Flaring involves burning off surplus oil and gas when producing or refining petroleum, or when producing petrochemicals. It is unwanted because energy/resources are wasted and the environment gets harmed. Norwegian regulations specify that flaring is only permitted on safety grounds, https://snl.no/fakling_-_petroleumsvirksomhet, accessed 27 January 2021. and energy losses also needed to be reduced. Increased oil prices meant these outgoings had risen many times over.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 233. Refineries – even such a young facility as Mongstad – had to modernise or die.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 1.

Another trend which emerged in western Europe during the 1980s was that many oil companies aimed to become as fully integrated as possible – in other words, participate in all stages of the industry from production, via refining, to product sales. When oil majors like Shell and Esso not only owned refineries but also produced oil, it was harder for Statoil to sell its crude – particularly under long-term contracts.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 17. While the oil market was demanding and undergoing change, it was clear that Statoil wanted to refine more of its own crude supplies. The question was whether Hydro wished to tag along.

To develop or not to develop

As early as 1980, the board of the state company was informed by the management of plans for an expansion and modernisation of the Mongstad refinery. Put briefly, Statoil was keen on a development while Hydro was sceptical. When the pair came to write a report on the issue for the Norwegian government, they found it difficult to reach agreement. One source of contention was how they were to characterise the profitability of the project. Hydro could accept that it might show a profit, but wanted to include the existing uncertainties. It felt Statoil was far too optimistic.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 229-231.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) saw no reason in January 1981 for a new consideration of the proposals. It felt that the planning and investigations could well continue, and that Statoil, Hydro and Norol had to agree between themselves on owner and operator conditions at Mongstad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 231. Hydro was operator for the refinery, a position it had negotiated when it sold half its 60 per cent shareholding to Statoil in 1976.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 265 (1983-84) to the Storting from the standing committee on energy and industry on modernising the Mongstad refinery: 6. https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=6&wid=aI&psid=DIVL1565. But remaining operator for a development it opposed was hardly appropriate.

Hydro’s reluctance was only partly based on the financial risk. The company had enough refining capacity for its own requirements and would prefer to use the money in other parts of its business.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 5

Statoil, for its part, was very positive about the development. Statfjord and Gullfaks coming on stream meant much larger oil supplies, and existing refinery capacity would compel the company to sell 90 per cent of these as unrefined crude.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proceedings, 1 June 1984: 4295, https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL647&pgid=c_1047&vt=c&did=DIVL136; Proposition no 98, op.cit: 16. It also agreed with the arguments outlined above that the refinery needed modernising to produce more light products.

While Hydro thought a less extensive modernisation would be sufficient, Statoil maintained that this was inadequate and could ultimately result in the refinery being shut down – as many others in western Europe had been.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 1.

Proposals to lease refinery capacity abroad as an alternative were rejected because Statoil wanted a facility tailored for the crude oil qualities found on the Norwegian continental shelf.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 234.

After the 1981 general election, it was clear that Norway would get a minority Conservative government. This was not entirely pro-Statoil, and therefore listened to Hydro’s doubts about Mongstad modernisation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 232.

Statoil and the MPE devoted the next few years to estimating how many work hours an expansion would require and whether the market conditions were suitable.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1990, Gjennombrudd og vekst: Statoil-år 1978 til 1987, Gyldendal: 286-287. Put briefly, the goal was to determine what the project would cost and whether it was profitable. This proved challenging, because the refinery would not be finished until the end of the 1980s and it was difficult to know what the next decade would look like.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 7.

The government was expanded in 1983 into a majority coalition with the Christian Democrats and Centre Party, and presented a White Paper in April 1984 on the Mongstad development. This estimated the total investment at NOK 4.2 billion. The MPE maintained that the project would be profitable, but nevertheless acknowledged that it would “depend on a complex set of factors, each which would involve great uncertainty”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Gunnar, op.cit: 24. The quotation is taken from proposition no 98, op.cit: 35. This uncertainty was also an issue when the Storting considered the development in June 1984. Despite the financial risk presented by the project, however, it received unanimous approval.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting proceedings, op.cit: 4314.

Expansion and modernisation

Statoil’s original plans called for annual capacity at the refinery to be expanded from four to 10 million tonnes, but whether the company could carry such a large project was uncertain. It accordingly proposed to reduce the annual increase to 6.5 million tonnes.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, op.cit: 284-285. The project also embraced a terminal and storage tank for crude oil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 98, op.cit: 18. Plans called for the work to be completed in early 1989. Hydro originally owned 15 per cent of the project, but pulled out in 1985.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statistisk vedlegg til §10-planen for 1986. Stavanger, 25 July 1985, National Archival Services of Norway: 57; ibid, 31 July 1986, National Archival Services of Norway: 17.1. It still held 30 per cent of the shares in the old refinery, but sold them to Statoil in March 1987 to leave the latter as the sole shareholder in Mongstad.

Statoil’s victory over the development proposals came with a bitter aftertaste. It was achieved as a consequence of the conflicts with Hydro and, not least, the disagreements over expanding the refinery. The bitterest outcome related to the financial and organisational consequences which the development and modernisation had for Statoil.