Inge K. Hansen – from listing to merger soundings

Like so many other senior executives in Statoil, Hansen has an MSc in business economics from the Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen. He subsequently worked for Bergen Bank and DnB before becoming CEO of Orkla Finans in 1994. With that background, he had detailed knowledge of the capital market – the new world Statoil had entered as a listed company. In early 2000, Hansen was recruited by Fjell as CFO to help lead the way to a stock market listing in 2001.

Hansen was at the centre of events when he stood on the balcony of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on 18 June 2001 to front the introduction of Statoil to the world’s largest stock market. He was sent there by Fjell, who remained at home for the opening on the Oslo Stock Exchange the same day.

Both CFO and CEO were strong supporters of privatisation and thereby continued to pursue former CEO Harald Norvik’s agenda.

Growth

One of the most important goals of the partial privatisation was international growth for Statoil. Establishing a presence in other countries could be valuable but was also complex and controversial – as the engagement in Iran had shown.

In his acting role, Hansen became responsible for taking the lead on the growth strategy until a new permanent CEO was put in place in March 2004.

He was soon involved in soundings over a merger with Norsk Hydro’s oil and gas business. That would continue the restructuring of the petroleum industry in Norway, which Statoil’s partial privatisation had also been part of. Moreover, this could help the company’s international expansion.

But that opportunity ran up against a fundamental tenet of Norwegian oil policy ever since the 1970s, when it was decided that Norwegian public and private interests in the petroleum sector should be balanced between a wholly state-owned company (Statoil), a partly state-owned company (Hydro) and a wholly private company (Saga Petroleum).

Statoil and Hydro had jointly taken over Saga in 1999 – and thereby sparked much debate.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nore, Petter, 2003. Norsk Hydro’s Takeover of Saga Petroleum in 1999. A Case Study, report 73, Power and democracy project report series, University of Oslo: chapter 3.3, https://www.sv.uio.no/mutr/publikasjoner/rapporter/rapp2003/rapport73/index-3_3_.html, accessed 2 May 2022. The question was whether the time was now ripe to abandon the last part of the “three-leaf clover” model.

There had been no lack of earlier calls for a merger. Fjell had expressed himself positively on the idea soon after becoming CEO. A few years later, chair Leif Terje Løddesøl aired the same thoughts – but without consulting either the rest of the board or the minister of petroleum and energy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rystad, Hans (NTB), “Steensnæs overrasket over Statoil-utspill”, Stavanger Aftenblad, 10 August 2002: 10.

In 2003, Fjell commented: “Clearly, we have assessed a merger of Hydro’s oil and gas business with ours. We’ve devoted a lot of time to it. There are both positives and negatives here. Our assessment is that this doesn’t represent a realistic alternative now. That doesn’t mean we can put it aside and forget it for ever. We wouldn’t be doing our job otherwise”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Vindegg, Anders, 2012. Når to skal bli én. En analyse av medienes rolle ved fusjonsforsøkene mellom Statoil og Hydro i 2004 og 2006, master’s thesis, University of Oslo: 40, quoted in Ask, Alf Ole, 2004. Hvem skal eie Norge?, Wigestrand: 71.

Soundings 2004

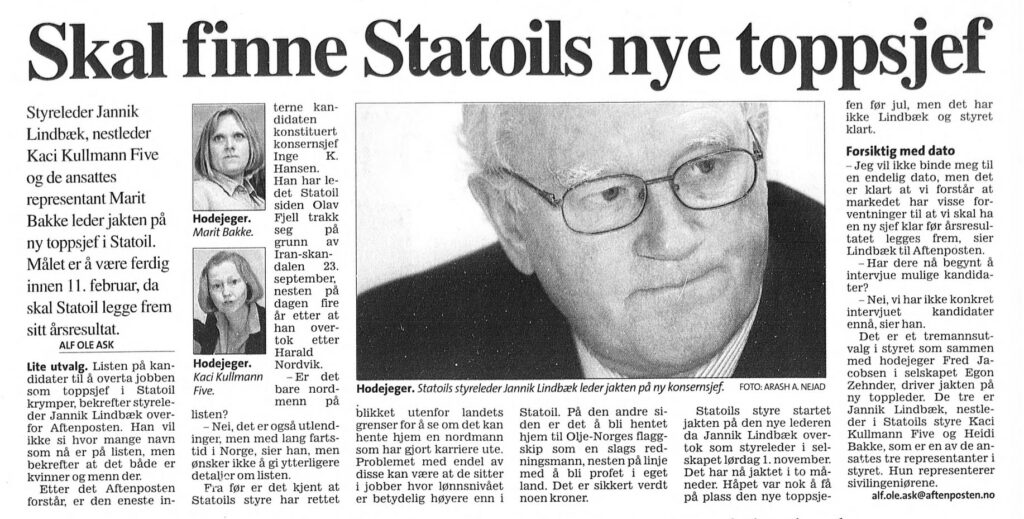

Hansen followed up this tradition in January 2004. At the initiative of chair Jannik Lindbæk, he raised the issue with Hydro CEO Eivind Reiten.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bøe, Arnt Even, “Defensiv Lindbæk tar ansvar”, Stavanger Aftenblad, 4 March 2004: 7.

These conversations were leaked to the public, and received a largely negative reception.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, 2022, En nasjonal kjempe. Statoil og Equinor etter 2001. Universitetsforlaget: 174. The mood in Statoil was sceptical over the timing of the soundings when the company lacked a permanent CEO and was still affected by the Iran affair. Some have ascribed the role as perhaps the leading mobiliser against a possible merger to former CEO Arve Johnsen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ask, Alf Ole, 2005, Hodeløse fusjonssamtaler. Report on journalistic methods to the Foundation for a Critical and Investigative Press (Skup), https://www.skup.no/sites/default/files/metoderapport/2004-25%2520Hodel%25c3%25b8se%2520fusjonssamtaler.pdf, accessed 2 May 2022. Local forces in Stavanger were important allies of the merger opponents for as long as people speculated whether the discussions had touched on where the head office for the merged company would be located.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Sammenslåing på sviktende grunn” (leader), 24 February 2004: 9. In that case, Oslo would be a clear alternative to Stavanger.

Hansen’s soundings were the last to bear no fruit. A couple of years later, Helge Lund – his successor as CEO – succeeded in achieving the merger. With hindsight, it appears that the attempt in 2004 provided important experience for the subsequent process.

The first lesson learnt was that such talks, at least from Statoil’s side, had to be entrenched politically in advance if they were to succeed. Second, the company had to have a sufficiently consolidated and stable position. Third, the process had to kept secret until agreement had been reached.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, op.cit: 182-187.

New CEO

Hansen’s chances of becoming the permanent CEO were weakened by critical comments from union representatives in the company, which related to what was seen as insufficient openness about Statoil’s involvement in Iran.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 106-108.

Lund was appointed CEO at the beginning of March 2004. He was then CEO of the Aker Kværner industrial group. In perhaps the best-known swap of top executives in Norwegian history, Hansen moved to Lund’s former job. The close business relationship between these two companies imposed a quarantine period, which meant Lund did not take up his new role until 15 August 2004. Similar restrictions applied to Hansen in his new job. Executive vice president Erling Øverland took over as acting CEO until Lund was finally in place.

As a former member of Norway’s national handball team, Hansen was very familiar with the importance of managing quick changes and the significance of timing. Such abilities were put to the test during his four eventful years at Statoil.

arrow_backStatoil’s Iranian adventureRollercoaster in the Gulf of Mexicoarrow_forward