Statex

Processing seismic data requires both computing power and technological insight, with the finished product going to geologists. They in turn interpret the material to try to determine how likely petroleum is to be found, and in what quantities. As Statex boss Bjørn Haug Hansen put it, the aim was to “separate the wanted from the unwanted noises and to calculate what these noises indicated”. The background for establishing the centre was that both owners saw benefits from combining KV’s insights and experience in computer systems with Statoil’s role as a substantial user of data processing services.

Before Statex appeared, seismic processing on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) was dominated by Geophysical Services Inc (GSI), a subsidiary of Texas Instruments. Agreement was reached by the newcomer with GSI on acquiring technology and taking over the American’s traditional share of the market. Statoil deputy chair Åge Solbakken objected to the establishment of Statex in a sharply-worded memorandum submitted to the board in November 1973. He maintained that the oil company had enough to do as it was, and that Norway already had a geophysical company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T and Nerheim, G, 1992, Fra vantro til overmot?, Norsk Oljehistorie, vol 1, Leseselskapet, Oslo: 293. The fact that Statoil’s longer-term ambition was to build up a seismic databank containing information which companies were obliged to share with government agencies was also seen as problematic – not least by representatives from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch and Nerheim, op cit: 293.

This job was allocated to the NPD, which still receives and administers all seismic data acquired on the NCS.

Nevertheless, the creation of Statex was approved by the directors against the votes of Solbakken and Vidkunn Hveding.

The main Norwegian player in the seismic surveying field, established in 1972, was the privately owned Geco. Externally, it claimed to be unconcerned about the competition. Statex “will concentrate particularly on data processing, while [we] also conduct survey work in the field,” said CEO Anders Farestveit.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende, 21 January 1974.

However, it transpired that Statex would also be pursuing seismic data acquisition. The company received a major assignment from the industry ministry’s oil office in its first year for such work off Finnmark in the far north.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjerke, Halvor Kr, 1989, På dypt vann: et høyteknologisk eventyr: 16.

As early as 1974, Statex was handling half of all data processing on the NCS – so its entry to the market was swift. Much of the work came from the government and Statoil itself. At that time, a certain rivalry prevailed between the NPD and Statoil. The two competed over recruiting and building up expertise in seismic surveying. This friction found expression in the allocation of work, with Statoil said to having given 70 per cent of its assignments to Statex while the NPD used Geco for 70 per cent of its work.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjerke, op cit: 17.

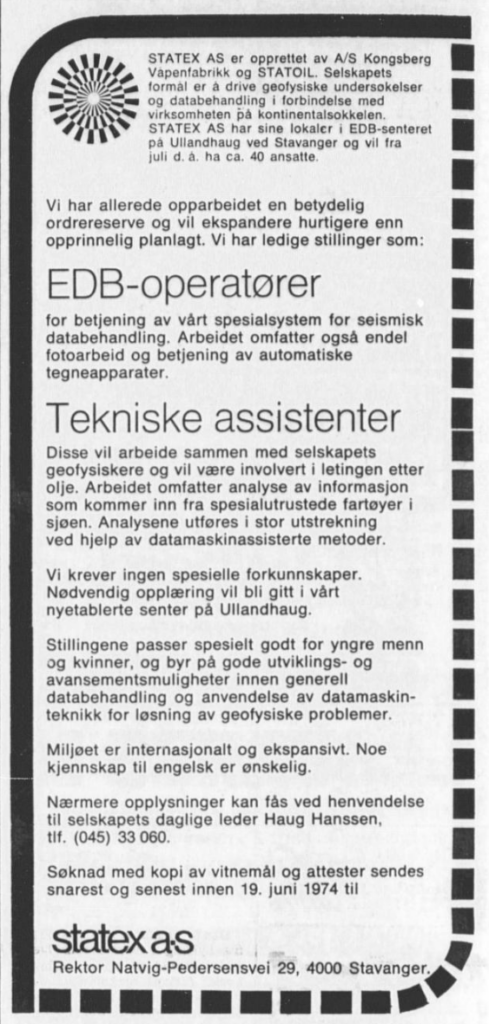

Based at Ullandhaug in Stavanger, Statex was intended to benefit from proximity to expertise concentrated in the nearby university college. The company grew quickly, had some 50 employees by the of 1974 and was constantly looking for more.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1988, Utfordringen: 93.

A year after its establishment, it became clear that Statex intended to do more than acquire and interpret seismic data. It wanted to establish a laboratory to analyse drilling samples. That followed a fight with the continental shelf office of the Norwegian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (NTNF) in Oslo, which was also interested in establishing and operating such a facility.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet, 7 April 1975.

Once again, the bulk of the work derived from Statoil. But Statex also conducted analyses – which previously had to be done abroad – for other companies on the NCS.

Through Statoil’s part ownership, Statex was widely seen as being the state oil company’s arm in the seismic survey field and a threat to diversity in Norway’s petroleum sector. It was unusual for an oil company to be a dominant owner in an enterprise providing services to the whole industry, and it was easy to sow doubt about both the award of contracts and the leakage of information from competitors to the parent company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjerke, op cit: 18.

Furthermore, opinion was divided on how far Statex was a “state organ” or competed on equal terms with other players in the same sector. Was its name, for example, a compound of “state” and “exploration” or of “Stavanger” and “Texas”, as some newspaper articles claimed?[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 20 July 1974.

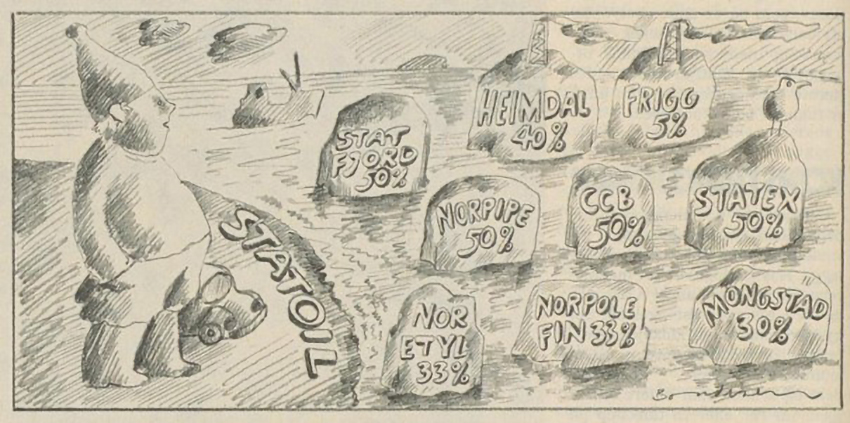

A number of politicians and participants in the public debate also believed that Statoil, by establishing Statex and the A/S Coast Center Base Ltd & Co (CCB) subsidiary at Ågotnes outside Bergen, had exceeded its original mandate and threatened diversity and competition on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 3 and 6 June 1975. That harked back to the discussions about changes to Statoil’s objects clause, which had been made without informing the Storting (parliament).

Both Geco and Statex eventually came to realise that Norway, at this early stage in its oil age, was too small to be able to develop two competing enterprises in such a technologically advanced field. Discussions initiated in early 1976 led to Statex becoming part of Geco with classification society Det Norske Veritas (DNV) and KV as 50-50 owners. This unification took effect in 1977, and Statoil sold its interest to KV. That took it out of the seismic acquisition and processing sector.