Securing the state’s royalty oil

Such military metaphors reflected the need to fight some battles to meet the goal of becoming a vertically integrated oil company. The aim was to forge an industrial chain extending from seismic surveying, via oil production, to service stations.

One of these fights involved securing control of the royalty oil – that share of production from the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) which the government had the right to demand from the licensees. Views differed over whether responsibility for this petroleum was a natural role for the state’s own oil company.

Picking a manager

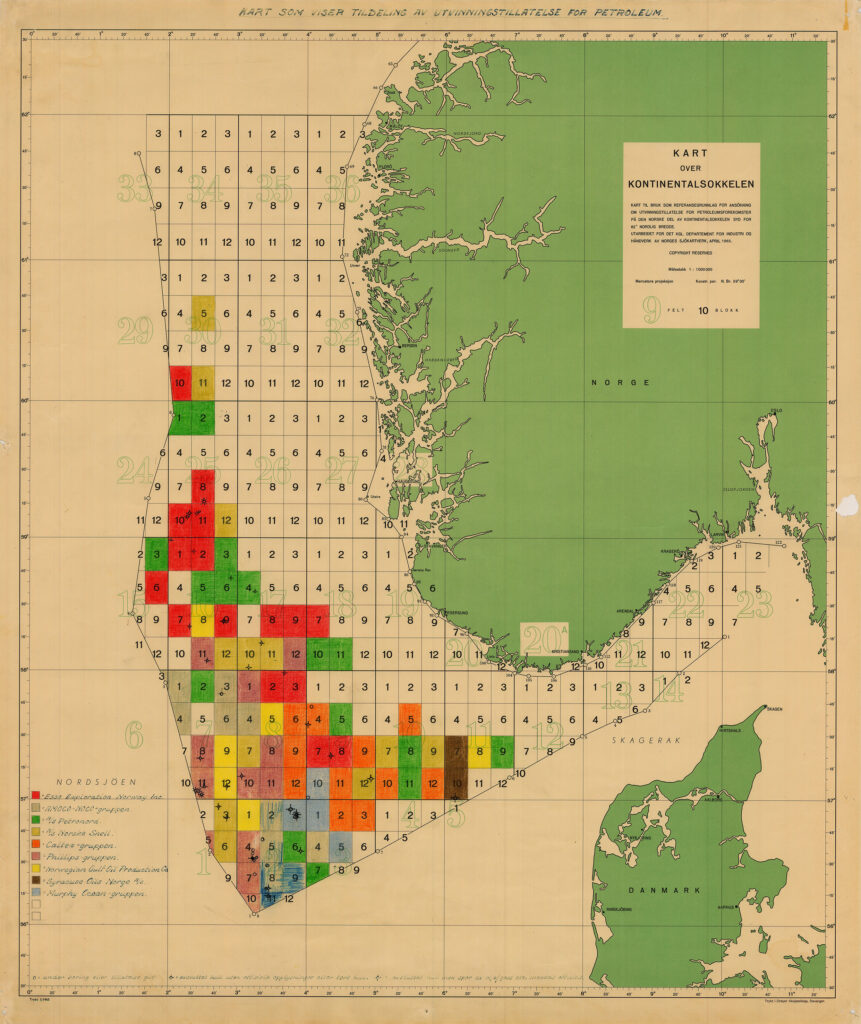

The licensing system for the NCS adopted by royal decree on 9 April 1965 built in many respects on the Norwegian solutions developed when awarding hydropower concessions in the early 20th century. Government revenues from the petroleum sector were to derive from two sources – taxes, and a direct share of the oil produced in the form of royalty once output had begun.

While tax is calculated as a percentage of profit, royalty represents a specific percentage of the production value. The oil companies therefore feared it more than tax. Given the scale of the investment involved, they had plenty to deduct from their taxable income. The same did not apply to royalty, which was paid on gross output.

Norway fixed its royalty on oil production at 10 per cent, a source of relief to the companies because it was lower than the 12.5 per cent charged by the UK. That was a conscious policy by the Norwegian government, with senior civil servant Jens Evensen as its leading advocate. A lower royalty was expected to attract foreign companies prepared to take the risk of initial exploration on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, Tore Jørgen and Nerheim, Gunnar, Fra vantro til overmot, Norsk Oljehistorie, vol 1, 1992: 419-426.

Since Ekofisk was the first Norwegian field to come on stream, it was also the first to become liable to tax and royalty. The decision to claim the latter was taken in 1973, when the initial period of trial production had ended.

Hauge and Johnsen took it almost for granted that the state oil company would be given the job of transporting, refining and selling this “royalty crude”. That would give the new creation practical tasks and sorely needed revenues.

Not everyone agreed. As with many other issues involving Statoil at the time, differences of opinion prevailed about the role the company ought to play. The non-socialists wanted to support private Norwegian enterprises, while the Labour Party believed that Statoil should be given more to do.

Norsk Hydro, which was majority owned by the state, asked in 1973 to be put in charge of the royalty oil. Ola Skjåk Bræk, the Centre Party industry ministry in the minority non-socialist coalition government headed by Lars Korvald from the Christian Democrats, thought it appropriate that the company – which had a 6.7 per cent state in Ekofisk – should also benefit from this state crude.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/participants-in-ekofisk/

Without even discussing the matter with Statoil, he decided in September 1973 to assign the sale of royalty oil to Hydro on the grounds that this would safeguard the company’s operations. It had received 113 000 tonnes as its share of Ekofisk production in 1972, but that was far from enough to meet requirements.

Hydro consumed 700 000 tonnes of petroleum products per annum in manufacturing fertiliser and other materials. The government’s royalty oil from the Phillips group as Ekofisk licensee, amounting to 300-400 000 tonnes per annum, would further help to meet Hydro’s needs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Tidens Krav, 26 November 1973. This decision was taken only a few weeks before the Korvald government resigned.

New parameters

The early 1970s was a time of frequent government changes in Norway. Trygve Bratteli’s first Labour administration had to quit on 18 October 1972 after just over a year in office. Since Bratteli had staked his position on Norway joining the European Community, the referendum victory for the opponents of membership meant his departure.

Korvald took over as premier, but only until 16 October 1973 when Labour won the general election. With Bratteli back in office for the second time, the Statoil leadership saw its chance to reverse the decision to put Hydro in charge of the Ekofisk royalty oil.

Another important incident at this time changed views on how the royalty should be paid. The relevant legislation specified that the ministry could decide at six-monthly intervals whether it wanted payment wholly or partly in produced petroleum or in cash.

The international oil crisis sparked by the war between Israel and neighbouring states in October 1973 resulted in a shortage of crude. Petroleum prices shot up and the rate of inflation, already high, rose even higher.

Norway and several other countries banned Sunday driving to cut consumption and prepared to introduce rationing. Given the need to take account of such emergencies, the government was no longer so concerned to sell its royalty oil but would rather retain it for domestic consumption.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap, 25 January 1974.

The law empowered the King to determine that licensees must deliver petroleum from their production to meet national requirements and ensure its transport to Norway. He could also determine who should receive these quantities. In the event of actual or threatened war or other extraordinary crises, the King could determine that licensees must make petroleum available to the Norwegian government.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1996-11-29-72. This was the right exercised in January 1974.

Under strong pressure from Johnsen and Hauge during the winter, Ingvald Ulveseth – the new Labour industry minister – resolved to alter the decision on administering the royalty oil. A letter from the Ministry of Industry on 18 January 1974 made it clear that Statoil, not Hydro, would be responsible for transporting and refining this crude.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap, 25 January 1974. Because of the oil shortage, the refined products would be made available to Norway’s new petroleum supply directorate.

Statoil reprimanded

While the acute oil crisis was resolved by the late winter in 1974, a new dispute over the royalty oil erupted in March. The bureaucrats in the industry ministry had become irritated by Statoil more or less dictating oil policy. Several such issues were in play at the same time.

On 5 March, the Statoil management with Hauge and Johnsen in the lead were carpeted by the ministry. The meeting was chaired by division head Knut Dæhlin, who had also called in the Attorney General and representatives from the Ministry of Trade and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Only one item stood on the agenda – Statoil’s management of the royalty oil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Njølstad, Olav, Jens Chr. Hauge – fullt og helt, 2008: 635.

Keen to put the Statoil management in its place, the bureaucrats asked who was responsible for determining that the state’s royalty was to be taken in natura – in other words, as crude – or as cash. Hauge had to agree that this decision rested with the ministry.

The next question was who should administer this oil. Hauge responded then that he considered the issue to have been clarified. Everyone knew that Ulveseth had overturned his predecessor’s decision.

Then came the crucial point: how was Statoil going to handle these commercial tasks? The ministry took the view that the company should not sell the oil on its own account but as an agent of the government, and should make no profit from this assignment.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 641.

That got Hauge to boil over. He had never “imagined the possibility that this was to be Statoil’s status”. Once the government had transferred to oil to Statoil at an agreed price, he maintained, the company must be able to take the same profit from its sale as any other commercial enterprise.

This view encountered stiff opposition from the ministry, and Hauge was reluctantly forced to accept that the company would submit a written report about its management of the royalty oil. The ministry would then decide what would happen next.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 642.

Tempers eventually cooled. Statoil’s board meeting on 13 March was told that the company had entered into a contract with Hydro, which wanted to buy royalty oil from Ekofisk. The sale would give Statoil a profit of roughly six per cent at a price of about USD 8 per barrel. It was then reported that some unwillingness had been expressed at the ministry over Statoil making a profit.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes, board meeting, Den norske stats oljeselskap, 13 March 1974.

The dispute over managing the royalty oil waxed and waned over the spring and summer, in part because disagreement prevailed within the government over how this issue should be handled.

Civil servants were critical that the company earned less by selling to Hydro than it could have made on the spot market, where prices had risen because of the oil crisis.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Njølstad, Olav, Jens Chr. Hauge – fullt og helt, 2008: 642.

Although the post-crisis supply position improved during the spring of 1974, the government continued to take royalty in the form of oil. And Statoil was entrusted with the job of transporting, processing and marketing this crude. That allowed it to establish contact with customers in the Nordic region and, eventually, in other European countries and the USA.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, Utfordringen, 1988: 98.

Good start with Labour backing

The issue of who should handle transport, processing and sale of royalty oil is one example of the way Statoil’s leadership applied pressure in the early years. Its aim was to secure acceptance for widening activities at Statoil to cover every business area and ultimately make it a vertically integrated oil company.

At the time, the boundaries for how freely Statoil could operate in relation to the political authorities and the ministry were not clearly defined.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch and Nerheim, op.cit: 330-331.

The non-socialist parties were not inclined to give it as free a hand as Labour, and allowed Hydro to take on the royalty job. But the second Bratteli government and Ulveseth supported the Statoil leadership’s ambitions and were willing to give it advantages in this case.

It was the state oil company’s job to manage common assets which were intended to benefit society as a whole. Responsibility for the royalty oil provided Statoil with an opportunity to become familiar with the market and to build up an organisation for taking on even more assignments.

arrow_backContending over capitalStatexarrow_forward