Rollercoaster in the Gulf of Mexico

Acquiring Ireland’s Aran oil company in 1995 first gave Statoil a small Houston department. Although this takeover was aimed at accessing the British and Irish markets, it included interests held by Aran in shallow-water leases in the Mississippi delta.

Subsea expertise boosts optimism

By the mid-1990s, Statoil possessed good expertise with subsea operated fields. Along with Norsk Hydro and Saga Petroleum, it had built up important experience in this area on Norway’s continental shelf (NCS). These Norwegian oil companies had learnt much from international majors such as Elf, Shell and Mobil, which had long track records in subsea development. Now they were themselves in the process of becoming world leaders for technology advances in deep water.

Soon after the Aran takeover, Statoil decided to try getting established in the deepwater areas of the GoM, while the original stakes acquired in shallow water were eventually sold off.

Oil exploration leases in the GoM were awarded through a straightforward auction process. The company participated aggressively in these bidding rounds, and its portfolio expanded quickly. In one round, it was successful with 31 of 41 bids. Statoil became the operator of five leases. The level of activity was high. In one area, the company participated with partners who included Texaco. But problems arose with a number of wells drilled by the latter and costs became much higher than planned. Statoil was also committed to chartering a rig to drill wells in the leases it operated.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, 2021, Femti år med oljeproduksjon: min historie.

By the end of the 1990s, the commitment in the GoM was loss-making. The sharp fall in oil prices at the same time prompted Statoil to reduce its international operations in a number of countries, and Statoil Energy Inc in the USA sold all its leases to Kerr-McGee. The Houston office was closed down.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1999 and 2000, Statoil.

With Maloney to the Gulf

As early as 2004, however, Statoil returned to the GoM. A key person behind this decision was William Maloney, the company’s strategist for expansion abroad who had been hired by CEO Olav Fjell in 2002.[REMOVE]Fotnote: About remuneration: https://www.dn.no/energi/houston/bill-maloney/statoil/sikret-seg-millionbonuser-i-houston/2-1-805338 and https://e24.no/olje-og-energi/i/nap8kB/han-ledet-equinors-usa-fiasko-og-knuste-bonustaket. Like Harald Norvik, his predecessor, Fjell was convinced that future growth for Statoil had to happen internationally. However, his lack of experience in the oil sector meant he needed people with international experience for gaining entry to petroleum activities in other countries. American Maloney was one of a trio brought on board to achieve this, which also included Richard Hubbard and John Knight.

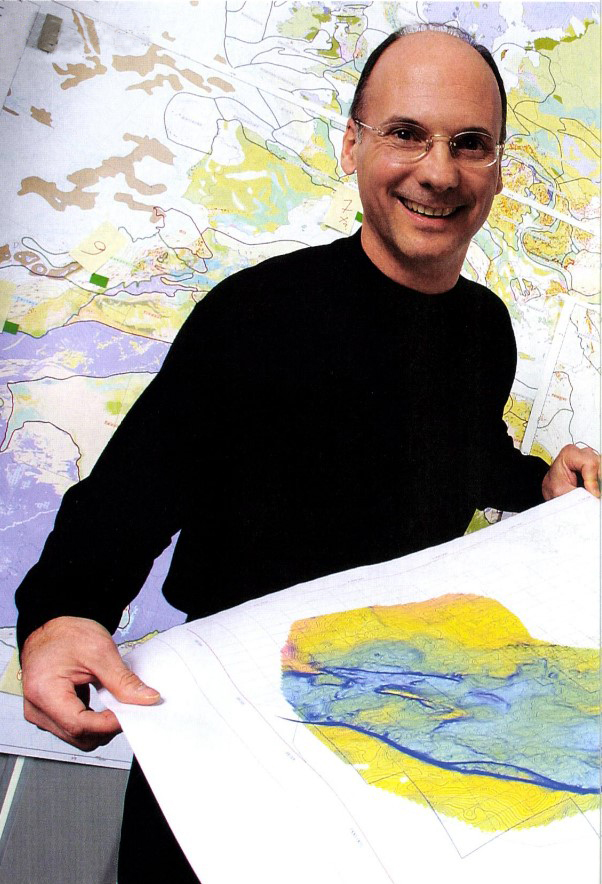

He came from a senior job at Texaco’s London office, where he had worked since 1996. Educated as a geologist, he began his career with Shell Oil Company in Houston in 1981. He was given steadily greater responsibility not only in the USA but also in the international market, and served as regional vice president for Latin America.[REMOVE]Fotnote: University of Houston website, accessed 1 June 2021.

Economic growth in many large economies, such as China, India and Brazil, led to increased demand for oil. Questions were asked about the possibility of shortages, and whether the members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) would be able to meet demand.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor in the USA, review of Equinor’s US onshore activities and learnings for the future. Prepared for Equinor ASA’s board of directors, 9 October 2020: 14. Oil prices rose month on month from 2002.

To benefit from this position, Maloney – who was very familiar with Houston – wanted the company to try its luck again in the GoM. The strategy was clear – begin as a partner before becoming an operator – and the top priority was to get into developments which would soon be on stream. After that, Statoil could turn to more uncertain but potentially more profitable projects.

The company could benefit from its subsea technology expertise. In Houston, it would be possible to continue developing a milieu with a high degree of innovation and very competent suppliers. Texas had a well-developed infrastructure, a stable regulatory and financial regime, and a well-established licensing system. This state had a long oil history and, unlike many of the other countries Statoil had moved into, was not unploughed ground. Maloney was well acquainted with the US system. In this open, competitive market, where acreage was bought and sold with great frequency, Statoil could quickly farm in and establish itself in a mix of producing fields and exploration leases.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, 2022, Equinors historie, vol 2.

Maloney’s strategy was met with great scepticism in Statoil’s Norwegian circles. But acting CEO Inge K Hansen listened to these proposals and helped to guide them through both the group management and the board.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. Statoil could thereby start to build a new GoM portfolio, and acquired an interest in an exploration prospect being pursued by America’s Chevron in early 2004.

In deep water

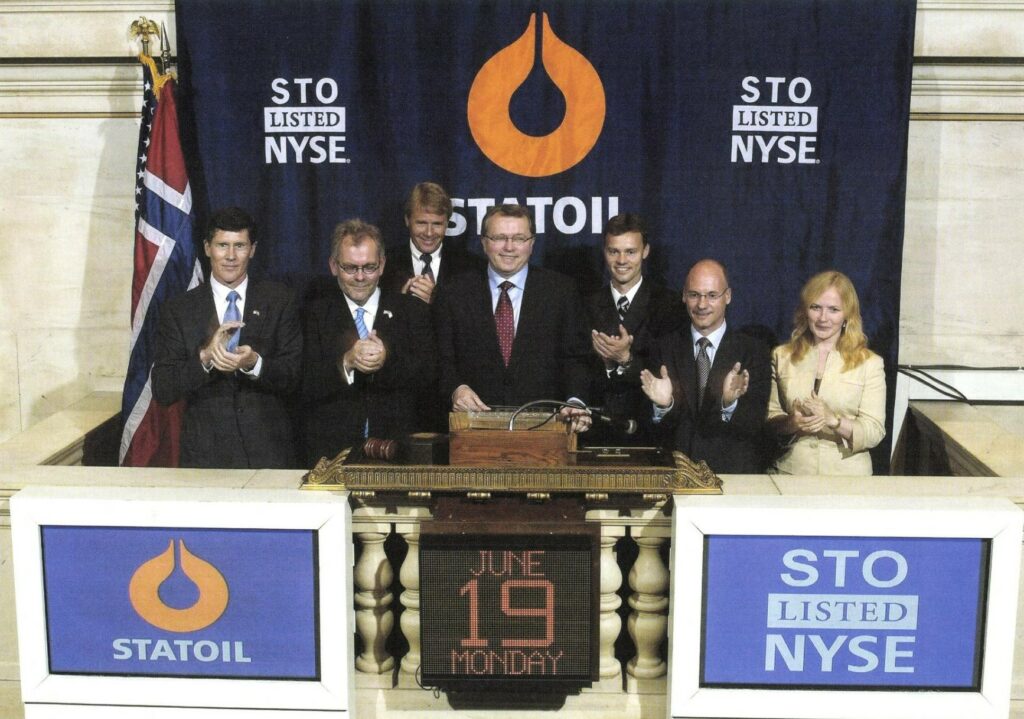

When Helge Lund became CEO in August 2004, therefore, Statoil had already returned to the GoM. This proved to fit well with Lund’s emphasis on continued international expansion. He strongly supported Maloney’s strategy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Årsrapport, 2007, StatoilHydro, “Store ambisjoner i Mexicogolfen”. The exploration strategy was approved by Statoil’s board in 2008, with the ambitious goal of becoming a leading producer and operator in the GoM.

Over the next three years, Statoil invested USD 3.6 billion in the GoM and secured interests in 400 leases and 11 discoveries.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, op.cit. Its annual report for 2006 anticipated that US production would be 100 000 barrels per day after 2021. The GoM had become an international core area for the company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2006, Statoil. The definition of a core area at the time was that daily production must be at least 100 000 barrels and that the company operated exploration and/or production licences.

Statoil farmed into oil fields in deep water which were being developed with Total and Chevron, and with Murphy Oil as operator.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2005, Statoil, https://www.offshore-mag.com/production/article/16789403/thunder-hawk-field-onstream. The company was the largest licensee in several discoveries which were expected to come on stream after 2013.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual reports, 2006 for Statoil and 2007 for StatoilHydro. All interests in shallow waters in the GoM were sold to Mariner Energy with effect from 1 January 2008.

Bringing these finds on stream presented many challenges. In addition to great water depths, the GoM reservoirs were deep beneath the seabed and the geology was complex. Thick overlying layers of salt made it difficult to identify petroleum deposits with seismic surveying. Moreover, compaction of the reservoir rocks made it hard to achieve high recovery factors.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro.

Hydro’s portfolio

As a result of the merger with Hydro’s oil and energy division in 2007, the latter’s GoM portfolio also came under Statoil management.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor archives, CEC, 3 September 2009, GoM portfolio overview. Hydro had acquired Spinnaker in 2005 for twice the amount Statoil – which also sought to take over this oil company – thought it was worth. It eventually transpired that a large part of the portfolio contributed by Hydro was not only overpriced but of such poor quality that it was sold off.

Despite this, the merged company’s annual report assessed the American part of the GoM to be one of the most interesting exploration areas in the world. Unlike other countries where StatoilHydro was involved, operating parameters in the USA were characterised by political and economic stability and predictability. It was also an advantage – as in Canada – that the oil and gas fields lay close to the world’s largest energy market.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2007, StatoilHydro.

The Houston office re-established by Statoil was expanding rapidly. It was located centrally in Westchase, on the city’s west side and inside the “energy corridor” where many of its business contacts were also based. The office initially covered exploration, drilling and development activities, with about 60 employees in 2004.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, op.cit. By 2007, it had increased to almost 250 staff and was set to expand further.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Årsberetning, 2007. op.cit. The biggest growth in employees came from buying up several other companies. After the Statoil-Hydro merger in 2007, the Houston office became the largest in the international department by both employees and number of licences.

How profitable?

As late as 2010, it was estimated that the deepwater proportion of world oil production would increase.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.offshore-mag.com/deepwater/article/16762692/deepwater-expenditures-to-reach-20-billionyr-by-2010. Even though such fields in the GoM were relatively smaller than discoveries closer to the coast of west Africa and Brazil, they had the advantage of good infrastructure and market access.

It might seem that Statoil was trying to do a bit too much at once in the USA. Although it belonged in the front rank technologically for developing fields with subsea wells and pipelines directly to land, this expertise failed to find its full scope in the GoM. A number of rigs were chartered in connection with the optimistic drilling plans. But the exploration team ultimately failed to mature enough targets to make full use of the capacity available, according to Helge Hatlestad, who was one of Statoil’s most experienced international staffers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, op.cit. Put simply, exploration drilling costs became too high in relation to revenues from the fields brought on stream.

At the same time, a technological revolution in oil and gas production on land in the USA threatened the profitability of deepwater developments. Once the method for recovering shale gas and oil had been commercialised, it was applied on a large scale. In 2008, 12 per cent of oil produced in the USA came from shale. That proportion was up to 35 per cent by 2012. Forecasts from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicated that the USA would become a net oil exporter by 2040.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.offshore-mag.com/production/article/16757111/technology-delivers-unconventional-results.

The StatoilHydro management saw which way the wind was blowing and also wanted to join in the “shale fracking dance”. During 2008, the company acquired a 32.5 per cent holding in a shale gas area in the USA’s Marcellus formation under an agreement with the Chesapeake Energy Corporation.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2008, Statoil. That marked the beginning of major investments in a new technology which later proved to run out of control.

Stayer in the GoM

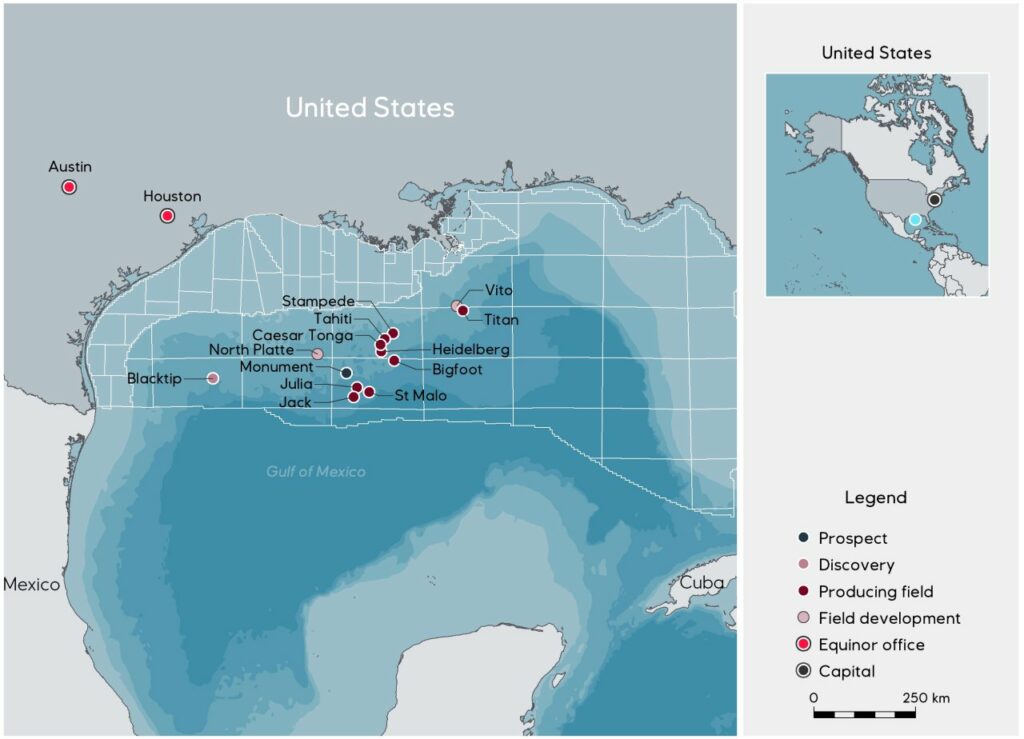

In 2021, Equinor still had a substantial involvement in the GoM. The company held 154 exploration leases, with a production of 123 000 barrel per day.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/news/archive/20201009-report-usa-business It was also continuing to explore. With partners Progress Resources USA Ltd and Repsol E&P USA Inc, Equinor found oil with its Monument wildcat in the central part of the US GoM. This was the company’s first own-operated exploration well in the GoM since 2015.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor’s website, 6 April 2020.

After the attention paid to what became a shale oil nightmare has receded, it appears that the GoM is where Equinor’s oil operations in the USA will continue.

arrow_backInge K. Hansen – from listing to merger soundingsHelge Lund – background and appointmentarrow_forward