Oil distribution under debate

Norway was a young oil nation in the mid-1970s. Big fields like Ekofisk and Statfjord had been discovered and production had barely got started on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). Statoil was established as the state oil company, and so was the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Many aspects of Norwegian oil policy had been debated and defined, but others remained unresolved.

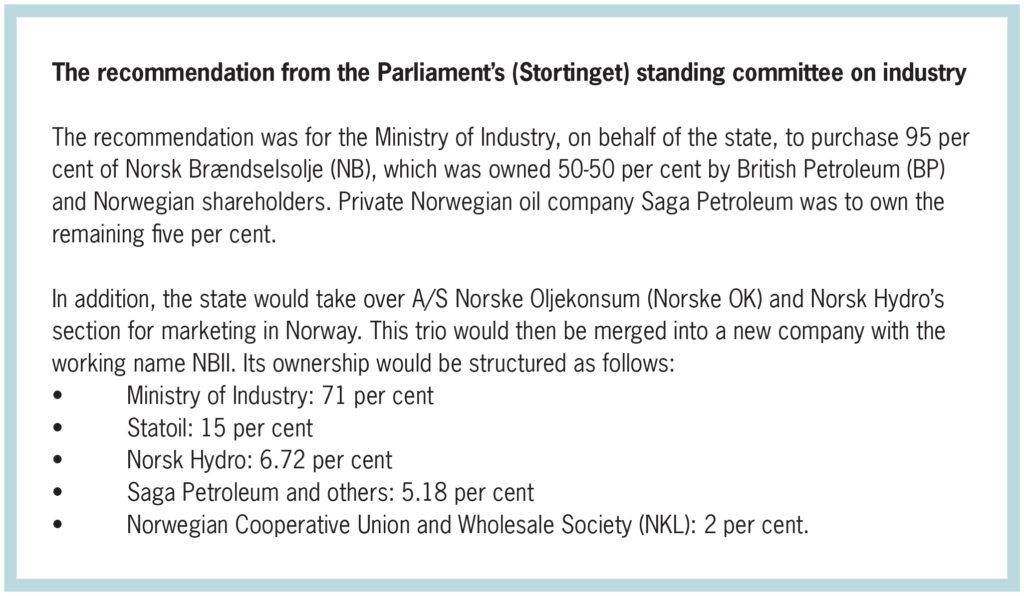

On 6 January 1976, the Storting (parliament) assembled to discuss a recommendation from its standing committee on industry concerning the purchase of Norsk Brændselsolje A/S, A/S Norske Oljekonsum/Norske OK and Norsk Hydro’s section for oil marketing in Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 254, 6 January 1976: 1975. https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1975-76&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL476&pgid=b_0409&vt=b&did=DIVL70. These acquisitions would be used to create a state-owned oil distribution company provisionally named NBII.

Presented by the Labour government, the proposal was expected to secure a majority with support from the Socialist Left.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 6 December 1975, National Library of Norway. But, although the issue had in many respects already been decided, the debate lasted from 11.00 to 23.00 with a three-hour break. No less than 38 representatives spoke a total of 90 times.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings, op.cit.

The Ministry of Industry, which was responsible for the plan, had already entered into frame agreements with the various companies. All that remained was the Storting’s consent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition (Bill) no 20 (1975-76) to the Storting, Kjøp av Norsk Brændselsolje A/S, A/S Norske Oljekonsum/Norske OK og Norsk Hydro a.s’ seksjon for markedsføring i Norge: 4. https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1975-76&paid=2&wid=a&psid=DIVL513. Industry minister Ingvald Ulveseth emphasised that the non-socialist parties could not opt for only part of the package – it was all or nothing. That was the main reason for the long debate by Norwegian parliamentary standards.

Principles under discussion

Reading through the Storting proceedings for 6 January 1976 shows that terms such as “principle” and “discussion of principles” were used by several non-socialist speakers. While Carl I Hagen, on behalf of the ALP, argued that this was something the parties should be able to decide without a lengthy debate, the Conservatives and the centrist parties – the Liberals, Christian Democrats and Centre – maintained that Labour should have provided space for a broader discussion on the shape of Norwegian oil policy. Did Norway need a new distribution company? Did it have to be state-owned? If so, how should it be organised?

Non-socialist representatives found it frustrating that the government was presenting a finished package to the Storting on a take-it-or-leave-it basis. The centrist parties, for example, could well imagine a “repatriation” of British BP’s shares in Norsk Brændselsolje (NB) to Norway, but were opposed to the state purchasing privately owned Norwegian shareholdings.

Moreover, a number of opposition representatives felt they had been given insufficient time to make their own investigations. Was it true, as Ulveseth claimed, that BP would only sell its 50 per cent NB shareholding if the Norwegian owners did the same? Or that the latter were not interested in retaining their shares if the state owned the other 50 per cent?

Both the Conservatives and the centrist parties tabled alternatives to the government proposals. Both the degree of state versus private ownership and Norwegian versus foreign ownership varied between these.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 258, 6 January 1976.

From international oil company to state control

Several answers were proposed to the question of how NBII should be organised. The Socialist Left at one extreme wanted maximum state involvement, while the ALP at the other saw no need for a Norwegian distribution company at all – whether privately or state owned. Labour wanted almost full state ownership, the centrists partial state ownership, and the Conservatives a completely private Norwegian company. Everyone except the ALP thought national ownership was important.

Hallvard Eika from the Liberals summed up the centrist standpoint: “The Liberals do not suffer from fear of the state … At the same time, however, we are convinced that Norwegian society should continue to build on a business community primarily composed of privately owned companies and other forms of non-state enterprise. That is the current structure, and should remain so in the oil age”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 2014.

The Socialist Left would preferably have excluded all the private companies – including Saga Petroleum – due to receive holdings in NBII and Mongstad refinery owner Rafinor. Its members argued that oil and gas were a natural resource like hydropower, and had to be under state control. Foreign companies must in any event be excluded.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 1991 ff.

Hagen, on the other hand, questioned what the foreign companies had actually done wrong. The ALP quite simply saw no reason to establish a Norwegian oil company at all, and accordingly proposed that the Storting should reject the whole proposal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 263, 6 January 1976: 2054 and 2026.

Conservative Olaf Knudson by and large agreed. He pointed out that state capitalism largely equated to unfree and undemocratic countries and, although Norway was not there yet, believed it was unfortunate that the state owned every third Norwegian industrial share. That was not least unfortunate when the government drew up the laws which also applied to companies it owned through the state.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 261, 6 January 1976: 2036 and 2054.

Another consideration was that companies sometimes needed to take quick decisions, which did not accord with the Storting’s demand for management and control.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135 (1975/76) to the Storting from the industry committee, Om kjøp av Norsk Brændselsolje A/S, A/S Norske Oljekonsum/Norske OK og Norsk Hydro A/S seksjon for markedsføring i Norge: 14, https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1975-76&paid=6&wid=aI&psid=DIVL1583. The Conservatives thought the Storting could adopt legislation and regulations which made state management unnecessary. A Norwegian company did not need to be synonymous with state ownership, maintained the party’s Odd Vattekar.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 254, 6 January 1976: 1981.

Prime minister Trygve Bratteli replied by asking the non-socialists to tone down their “old-fashioned fear of socialism”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 261, 6 January 1976: 2038.

Overly expensive?

Labour and the Socialist Left wrote in the committee recommendation that the state would benefit from buying into the distribution market and that this could done without “being at the expense of other important social tasks”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135, op.cit: 9. The government would not be borrowing money for the purpose nor drawing on the budget. Funding would come from the anticipated oil wealth. According to the government, this was cash which would otherwise be placed in foreign bank accounts to the benefit of capitalistic bank owners.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 263, 6 January 1976: 2050.

None of the non-socialist parties accepted that argument.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 2025-2026 and 2028. In their view, the funds could well be used for something else. They believed, on the contrary, that it was a waste of taxpayer money – not least considering the high price being paid for the shares.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 259, 6 January 1976: 2022, 2055, 1998 and 2048; Willoch, Kåre, 1990, Minner og meninger, vol 3, Statsminister, Schibsted. Oslo: 298-299.

That price was the subject of a number of newspaper articles, with headlines like “Acquisition of Norsk Brændselsolje. Government paying 140 per cent too much”, “Agreed price too high”, and “Irresponsible treatment of funds held in trust”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Respectively Nordlandsposten, 13 December 1975, Stavanger Aftenblad, 6 January 1976, and Drammens Tidende og Buskeruds Blad, 6 January 1976, National Library of Norway. While a right-wing party newspaper[REMOVE]Fotnote: Until roughly the mid-1980s, most newspapers in Norway were affiliated to a political party – either directly as a party organ or through explicit or implicit support. That applies to the newspapers cited here. https://snl.no/avis, accessed 2 June 2020. presented proof that NB was overpriced given its earnings in recent years, another paper with an affiliation further to the left published an assessment that NBII had good opportunities to earn well in coming years. The non-socialist parties believed one story, the socialists another.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Including Nordlandsposten, 13 December 1975, and Moss Dagblad, 15 December 1975, National Library of Norway.

Labour and the Socialist Left maintained that “bookkeeping” principles could not be prevail to the exclusion of all else. Not everything could be measured in cash. It might, for example, be relevant to “give [NBII] special obligations” related to regional policy – such as maintaining service stations in out-of-the-way areas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135, op.cit: 9.

Leading Conservative Kåre Willoch wrote later that, when politicians presented arguments like “regional policy considerations” and “social considerations”, it was a sign that they had few good economic arguments. He was referring to the Mongstad refinery, but could equally well have cited the creation of NBII.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Willoch, Kåre, op.cit: 298.

A number of voters were positive to establishing a state-owned distribution company. A Gallup poll for the morning edition of Oslo daily Aftenposten on 27 September 1975 showed a majority of the general public in favour of the government acquiring BP’s distribution network.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten (morning edn), 27 September 1975, National Library of Norway. Employees at the various forecourts were also largely positive.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Arbeiderbladet, 25 August 1975, National Library of Norway.

Where the socialist parties were concerned, a great deal of idealism was involved in establishing NBII. They generally called it the last link in the oil chain. That also applied to a certain extent in the centrist parties, which wanted to secure repatriation of foreign interests. For a party like the Conservatives, however, it was out of the question to support an acquisition which was not “financially justified” but “purely political”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, no 261, 6 January 1976: 2036.

Majority with subsidiary support

The voting stage was finally reached late in the evening. A Socialist Left motion to exclude Saga from NBII and give both that company and Rafinor[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rafinor was the company that owned Mongstad refinery. as much state ownership as possible was defeated. So was the ALP’s motion to drop the whole idea, and the Conservative call for more private initiative. The centrists lost their motion to repatriate the BP shares but otherwise retain private owners. And the supplementary New People’s Party (NPP) motion on an initiative for more private involvement was also felled. With subsidiary support from the Socialist Left and the NPP’s sole representative, the government’s proposal was carried by 78 to 74 votes.

In other words, and entirely in line with expectations, the government plan for a new state oil distribution company won the day. Statoil, Hydro, Saga and the Norwegian Cooperative Union and Wholesale Society (NKL) received shareholdings of varying size in the new company, but the state had the majority. The further result of the Storting vote was that the state owned 40 per cent of the shares in Rafinor through NBII, with Hydro and Statoil holding 30 per cent each.

Norway had secured a state-owned company for oil distribution and marketing, and Labour was close to achieving its goal of state participation in all stages of the petroleum industry.

Norol’s the name

NBII could continue to use its existing brands for a limited period, but was clearly going to change its name quickly.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 20, op.cit: 26. Oslo daily Dagbladet suggested jokingly and somewhat ironically that the new company should be called “Ingoil”, allegedly in recognition of Ulveseth, who was stepping down as industry minister.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet, 7 January 1976: 2, National Library of Norway. Unsurprisingly, this suggestion was not picked up.

An extraordinary general meeting on 19 February 1976 resolved to call the company Norsk Olje a.s, with Norol as its brand name.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 20 February 1976: 17, National Library of Norway. This was announced in a press release, and the former OK, NB and Hydro service stations were rebranded during 1976. Norwegian could then buy wholly Norwegian oil recovered from beneath the North Sea, refined at Mongstad and distributed by a state-owned oil company with a livery in the national colours of red, white and blue.

arrow_backRigged for successFrom dependence to master in its own housearrow_forward