From dependence to master in its own house

In 1976, four years had passed since Statoil was established and seven years since the discovery of the Ekofisk field. Norway had barely become a petroleum nation. The Labour government under Trygve Bratteli believed the time was now ripe for the Norwegian state to move from dependence on the international oil companies to mastery of its own petroleum industry – including the domestic market for oil products. Both Labour and the Socialist Left Party wanted the greatest possible integration of oil policy, with the state in control from seismic surveying to the petrol pump.

According to Labour, an overall national oil policy also had to encompass such downstream activities as refining, distribution and marketing. These ambitions could only be achieved with state involvement.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135 (1975-1976) to the Storting: 8. Securing opportunities for Norwegian participation downstream would become more and more important as the state acquired larger supplies of crude oil, particularly through anticipated production from Statfjord.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 10; Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 2000.

As early as 1975, the Labour government had started working to establish a new state-owned oil distribution enterprise by acquiring three existing downstream companies.

The proposal and its motivation

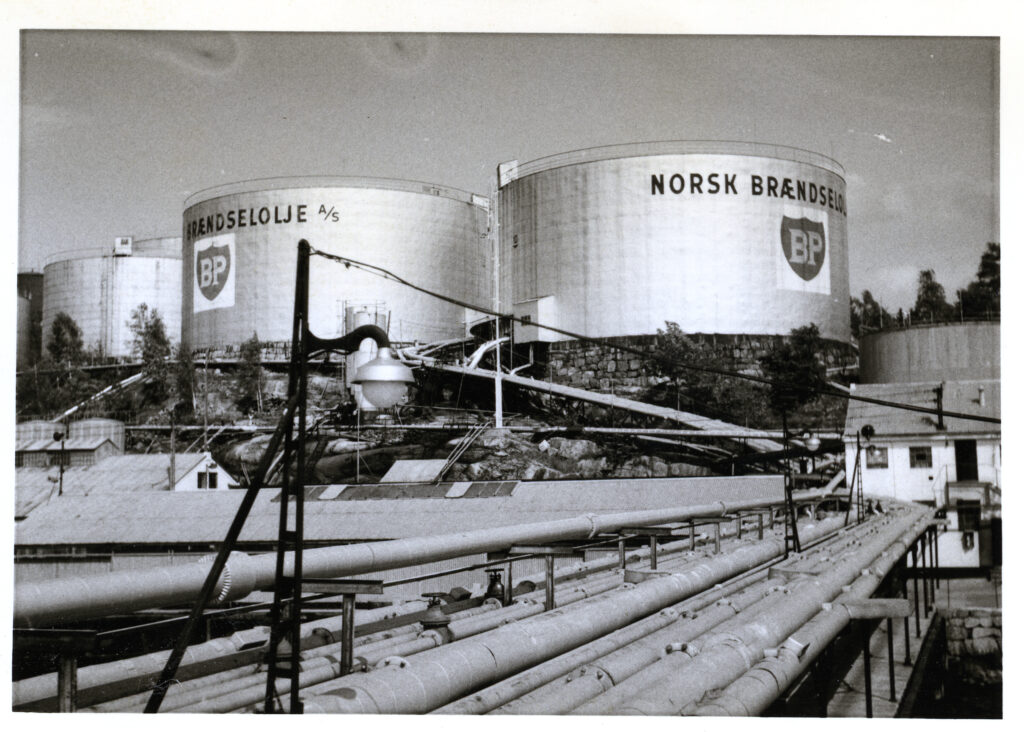

The idea was for the Ministry of Industry, on behalf of the state, to purchase 95 per cent of Norsk Brændselsolje (NB), which was owned 50-50 per cent by British Petroleum (BP) and Norwegian shareholders. Private Norwegian oil company Saga Petroleum was to own the remaining five per cent. In addition, the state would take over A/S Norske Oljekonsum (Norske OK) and Norsk Hydro’s section for marketing in Norway. This trio would then be merged into a new company with the working name NBII.

Its ownership would be structured as follows:

| Ministry of Industry | 71 per cent |

| Statoil | 15 per cent |

| Norsk Hydro | 6.72 per cent |

| Saga Petroleum and others | 5.18 per cent |

| Norwegian Cooperative Union and Wholesale Society (NKL) | 2 per cent. |

The acquisition would also include NB’s 40 per cent shareholding in the refinery at Mongstad. Norsk Hydro’s 60 per cent holding in this facility was also halved to 30 per cent, with the other 30 per cent going to Statoil. The company which owned Mongstad was to be known as Rafinor.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 1-5.

In the government’s view, this constellation would create a strong company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 2002. With a market share of 20 per cent, NB was the third largest distribution company in Norway after Esso and Shell and had sales outlets nationwide.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135, op.cit: 2 Norske OK was confined to Trøndelag plus southern and eastern Norway, and also supplied cooperatives and the Agricultural Purchasing and Marketing Cooperative. The government maintained that a cooperation between NB and Norske OK would have regional policy and consumer benefits. In addition, involving the latter would give the new enterprise contacts with the NKL, which was also to be a shareholder.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 20 (1975-1976) to the Storting: 19-22 and 28-29. And acquiring Norske OK allowed the government to buy out its Swedish part-owners.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 1982.

Hydro had virtually no service stations, but those it had were used to sell surplus oil stocks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proposition no 20, op.cit: 22. Acquiring its marketing section would allow the government to avoid competing with itself, since the state already had a big stake in Hydro. It would also allow the latter to concentrate on its core petrochemicals business and free up a good deal of capital.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 1982 and 2003.

A strong motivation for choosing NB rather than Shell or Esso was that the state would thereby acquire a big shareholding in Mongstad. Although Shell also had a refinery at Risavika outside Stavanger, the Mongstad facility had room for expansion. Industry minister Ingvald Ulveseth told the Storting (parliament) that further development there would also be good regional policy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 2000. However, the most important consideration was undoubtedly that NB was already regarded as the most Norwegian of the big three retailers since domestic shareholders owned 50 per cent. Acquiring BP’s share in addition ensured repatriation and a wholly Norwegian-owned company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135, op.cit: 8

That fulfilled Labour’s ambitions of creating a national distribution company. “Norway will cease to be a vassal in the oil industry,” a Labour speaker in the Storting debate on the acquisition declared. “We’ll have master’s rights to an important part of the Norwegian economy.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 2002: 1983.

Two main considerations underpinned the decision to take over existing companies rather than build up a new one. First, it was expected to be cheaper to acquire going concerns, with an established customer base and infrastructure. Second, and perhaps most important, the distribution sector was under financial pressure and the government thought it unlikely that room existed for another service station chain in this market.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Recommendation no 135, op.cit: 8

Ownership directly or via Statoil

A natural question was why the state should be the main shareholder in NBII rather than Statoil or Hydro, its existing instruments in the petroleum sector. When the media raised this issue as early as June 1975, it was under such headlines as “Statoil to take over 1 300 BP stations” and “Statoil wants to buy BP’s facilities”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende, 9 June 1975; Fremover, 10 June 1975. Another read: “Statoil/BP: petrol and oil. Norsk Hydro: petrochemicals”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Morgenbladet, 10 June 1975. “Statoil” was later replaced by “the state”. Whether the press had misunderstood or the Labour government had changed its mind is difficult to say.

Ulveseth wanted Statoil, like the big international companies, to become fully integrated. That also accorded with the 1972 object clause in the company’s articles of association, but support for this ambition was lacking in the Storting.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Anon, 1990, “Perioden 1970-1976”, 70 år: 1920-1990, Oslo: 30. A natural conclusion is that the Socialist Left, which supported the minority government’s takeover proposal, would not have done so if Statoil was to become the majority shareholder. So why not Hydro?

As noted above, the government wanted that company to concentrate on petrochemicals.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting, 6 January 1976: 1982 and 2003. A natural comment is that it should then have allowed it to retain its stake in Rafinor. A number of opposition politicians, particularly from the Centre Party, were critical of diminishing Hydro’s status to Statoil’s benefit.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 1987-1990. The government’s desire to give the latter a holding in Mongstad reflected its awareness that Statoil and the state, as mentioned above, would soon need a place to refine Statfjord oil. It could also reflect Labour’s general preference for Statoil compared with Hydro.

Storting approval

As expected, the socialist majority in the Storting voted on 6 January 1976 in favour of establishing NBII, which was soon named Norsk Olje (Norol). Labour thereby felt it had secured virtually complete mastery over Norway’s oil industry. BP lost its downstream foothold and the Norwegian state now controlled what Labour called a complete oil chain – an integrated oil policy.

arrow_backOil distribution under debateKeeping parliament informedarrow_forward