New life for Frigg gas field?

The Frigg field was proven in 1971 in 100 metres of water by French oil company Elf as operator. Its sandstone reservoir in the Frigg formation lies at a depth of 1 900 metres, and the gas comprises 95 per cent methane plus a little condensate. This combination of reservoir and petroleum type created good production properties. A plan for development and operation was approved in 1974.

Two nations – two pipelines

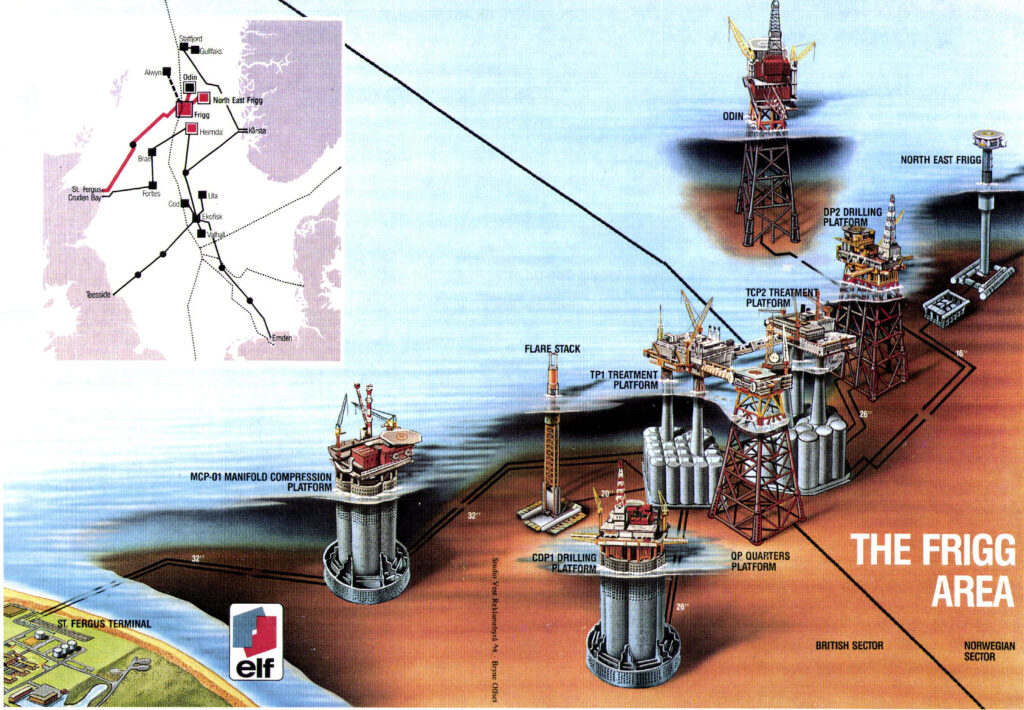

Britain provided the market for the gas, so that was where a pipeline to carry it had to go. Since the field was shared between Norway and the UK, two 360-kilometre lines were planned to carry production from its Norwegian and British parts. That provided full control over how much gas was produced on either side of the boundary – which was naturally significant for the producers when selling the gas.

Platforms on both sides

Development of the field embraced four installations on the UK side of the boundary, which came on stream in 1977, and two on Norway’s share. These started production the following year.

The British facilities included a concrete drilling platform (CDP1) with 24 wells and a treatment platform (TP1), both with a concrete gravity base support structure (GBS). In addition came a flare stack and the quarters platform supported on steel jackets.

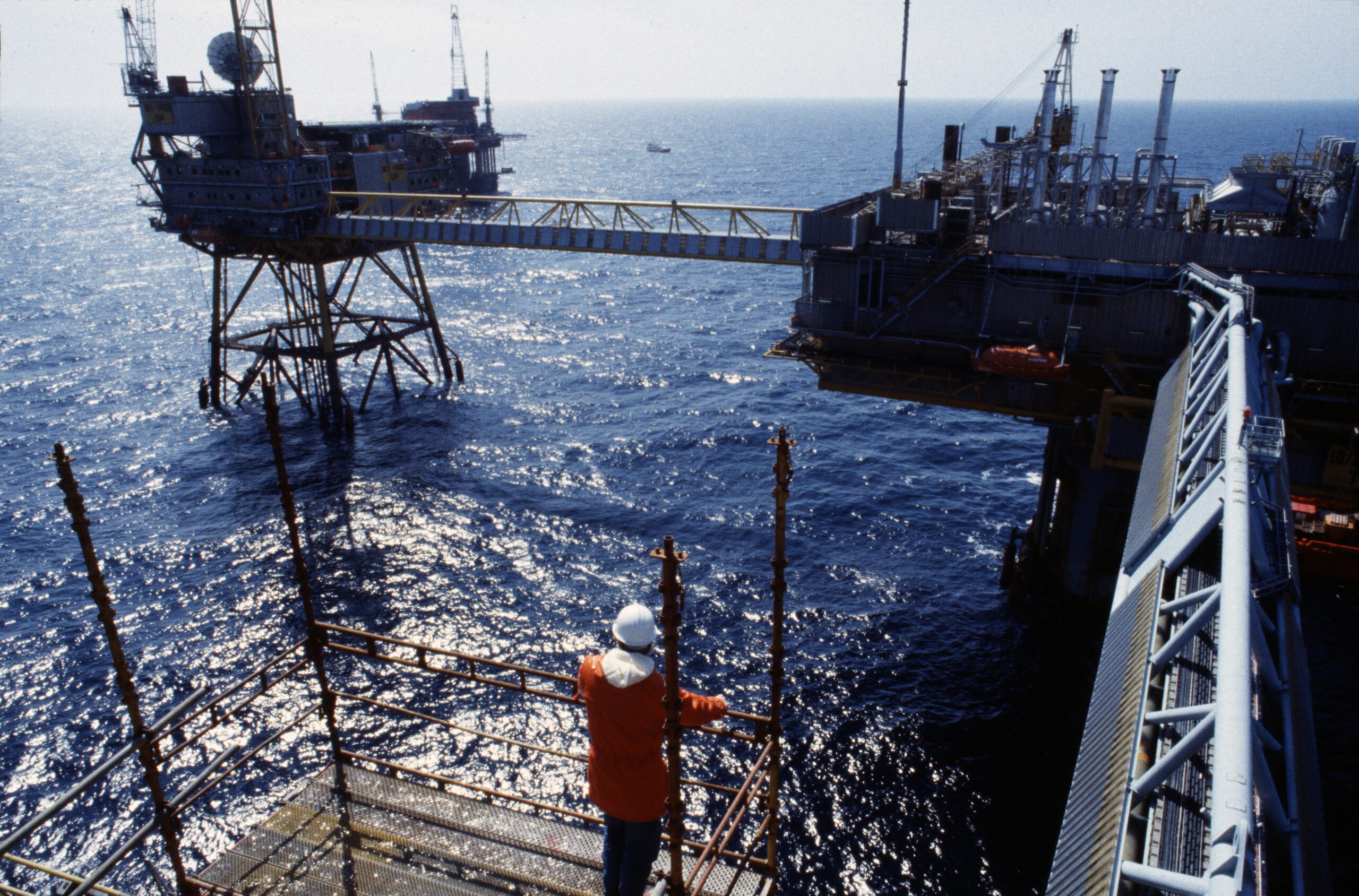

The last of these installations accommodated personnel from both sides of the field. A bridge from one of the Norwegian platforms to QP was the only point where it has been possible to cross dryshod between the two countries.

Norway’s installations were a second drilling platform (DP2) and a treatment and compression platform (TCP2). As Norwegian satellite fields to Frigg were developed, the latter facility was also upgraded to receive gas from North-East Frigg, East Frigg, Lille-Frigg, Frøy and Odin.

Mention could also be made that a concrete manifold compression platform (MCP1) stood midway between Frigg and Scotland to maintain pressure in the pipelines to the landfall terminal at St Fergus.

Valuable gas

Frigg meant a great deal for Norway as a gas nation, for the Norwegian economy and for its licensees, while production from the field and its satellites was very important for UK energy supply. In the early 1980s, Frigg accounted for about a third of gas consumption in the British Isles.

Developing this field also made an important contribution to developing technology for the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) and to Norway’s offshore supplier industry – particularly with regard to subsea solutions.

The licensees were taken by surprise – in a positive way – to discover that Frigg contained 40 per cent more gas than originally thought. Estimates suggest that 78 per cent of the gas in the reservoir was recovered. That met the Norwegian government’s goal of a 75 per cent recovery factor, and by a good margin.

Shutdown, removal and new plans

When Frigg was shut down in 2004, the installations clearly had to be removed. That job was completed in 2010. Some components still remain, including three GBS structures – TP1 and CDP1 on the UK side and TCP2 in the Norwegian sector. These have been allowed to stay because removing them would be much too complex and costly.

A production licence embracing the Norwegian side of Frigg was allocated to Equinor in 2016 as part of an awards in predefined areas (TFO) round, and the company is assessing a redevelopment. New subsea technology with seabed wells could make this profitable. These solutions are cheaper to operate than manned platforms. A network of seabed wells covering a large part of the reservoir could increase the recovery factor even further.

If such plans are realised, new subsea templates on Frigg would form part of a large unitised development in the area of the NCS between Oseberg and Alvheim. An appraisal well was drilled on Frigg in 2019. Equinor also holds the licence rights on the UK side of the field, which were extended in 2019.

Frigg has been documented in detail by the Norwegian Petroleum Museum and has its own Industrial Heritage Frigg website with much interesting material.

arrow_backIn the driving seat for subsea compressionOil exploration in Uruguayarrow_forward