From telex to Teams

Ensuring that information storage and sharing work as they should is crucial for an oil company with operations offshore and on land, in Norway and internationally. Such functions must be fast and secure, not least to prevent commercial secrets going astray.

Requirements in this area have changed as the organisation has grown and opportunities provided by new technology open new vistas. Developments have followed the same pattern as in other companies and are by no means unique to Statoil/Equinor. But many employees believe it has always been a front runner in adopting new technology. That has created both pride and pleasure – as well as frustration. Some reminiscences of those who experienced the changes are presented below.

Time of the telex

During the early years, the typewriter and the telephone were the most important tools for office staff. Letters were sent by post. A big improvement was the introduction of typewriters with correction keys around 1980.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by May-Britt Lunde on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 26 November 2019. The telex[REMOVE]Fotnote: The telex is a global telecommunication service where each subscriber is equipped with a terminal linked to telex exchanges, permitting typed messages to be exchanged directly. and eventually the telefax made communication significantly more efficient.

“Tick, tick, tick … Every morning, telex messages ticked in from the drilling rig with details about the number of metres drilled the previous day, wind and weather conditions, geological conditions, downhole pressure and many other details,” recalls Gjertrud Lindberg. Six-seven of these machines were in use – it could be pretty noisy at times.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Anvor Rasmussen on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 10 January 2020. Telex messages on long strips of paper were stored in folders.

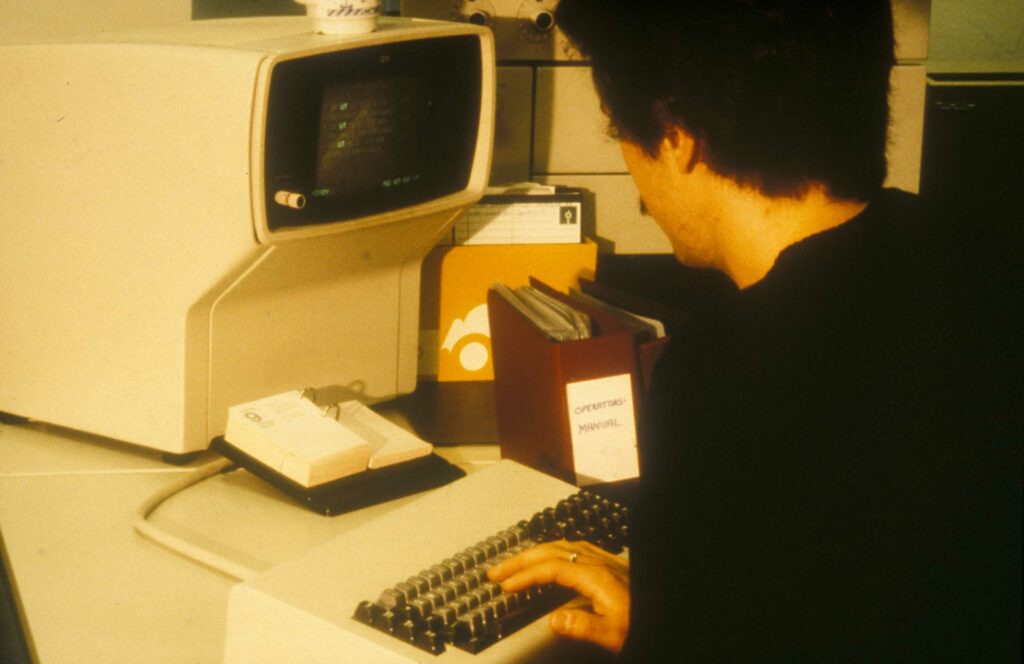

From telex to computer

More wells were drilled in the 1980s, and activity on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) was high. The volume of paper kept pace with this expansion. Idar Johnsen, in charge of NCS drilling, then proposed using computer technology to ensure an overview and simplify the analysis of information related to an individual drilling rig. A project team was established to develop and introduce the daily drilling reporting system (DBR). When the new solution was ready, opposition to its adoption was strong on one rig in particular. What was the point of a PC, crew asked. After all, the telefax[REMOVE]Fotnote: A telecommunication service which makes it possible to transfer letters, drawings, photographs, handwritten notes and so forth, usually via the telephone network, so that the recipient receives an exact copy of what has been sent. functioned well. “It was as if workers with worker hands didn’t have fingers suited to a keyboard,” observes Lindberg. Nevertheless, things gradually went better. Those who had been the strongest opponents sometimes became the biggest enthusiasts, and came up with their own proposals for improving the programme.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Gjertrud Lindberg on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 10 January 2020.

IT step

The internet was introduced to the company in 1995. Employees had to apply for connection and explain why it was required. A monthly fee of NOK 130 was deducted from the employee’s pay, and they then gained access to Netscape, the user manual and user support.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

It did not take the company long to establish its first external website and intranet, based on pure HTML coding. They were not particularly user-friendly, and little content was initially produced. That changed as new software from Lotus was introduced, Lindberg recalls.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

A unanimous board decided in 1996 that all 9 000 employees in the parent company would be offered a home PC and ISDN phone line through a programme called the IT step. At the time, a PC was a relatively expensive piece of equipment which cost NOK 20 000 and was far from usual in all homes. Many employees appreciated the offer and gladly devoted their free time to acquiring computer skills. Some of the older personnel nevertheless regarded it as a nightmare, and the need to take a test after completing the training was considered particularly frightening. Younger people usually managed well.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Leif Berge on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 27 July 2019.

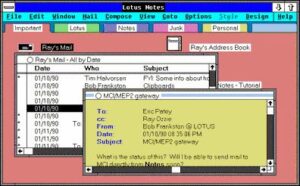

Lotus Notes suite

One set of applications introduced in 1990 which long endured in the Statoil/Equinor system was Lotus Notes. This software made it simple to tailor solutions for many different purposes.

First, it functioned as an electronic mailbox. Since the programme was simple and intuitive to use, e-mail was introduced to Statoil as an everyday work tool.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Iver Poppe on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 5 October 2020. Nevertheless, the story goes that some people refused to open e-mails, and swore by the phone instead.

Second, Notes could be used to manage documents and other information in databases. Their content could thereby be shared in a simple way across the company and national boundaries. Some of these databases were developed and maintained centrally in the company, while others were created locally for anything from a handful to a few hundred users. They could meet individual requirements, such as maintaining an overview of everything from keys and cupboards to scaffolding on a platform.

Together with the IT step, Lotus Notes helped to shift the whole organisation in a digital direction.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. Its use expanded quickly and it became ever more popular. Within a few years, the number of Statoil users had reached 5 500 – not only in Norway, but also in such locations as the USA. The fact that the computer system was served from Norway and user support followed Norwegian working hours could be a problem for those in other time zones.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Ivar Tresselt on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 13 September 2020. But the programme itself was not responsible for that.

As new software became available, the decision was taken to phase out Notes. Microsoft Word and PowerPoint replaced corresponding components in the Lotus suite. When Statoil merged in 2007 with the oil and energy division in Norsk Hydro, a major phasing-out project was instituted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Jane Marie Eide on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 5 January 2020. But getting rid of Notes proved difficult. Although most databases in the software were replaced in 2020 by Teams sites and Sharepoint, 100 “irreplaceable” databases remained to be eliminated.

Integrating with SAP

Another computer tool with a long life in Statoil was the Systems Applications and Products in Data Processing (SAP) software. The decision was taken in 1996 to introduce this German software, which was adopted by the whole oil industry at this time. It was an administrative computer tool for controlling the company’s procurement and supply activities.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kongsviks, Trond Øystein, 2006, PhD thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). With German precision, it could be used to keep track of most things – including individual functions such as time writing for employees. The programme was intended to help standardise and simplify the group’s administrative processes.

The ambitions underlying the adoption of SAP were boundless. According to CEO Harald Norvik, it was far more than an IT project – the aim was improvement and enhanced efficiency. Through the better, faster administration programme (abbreviated BRA, which also means “good” in Norwegian), new working methods were to be developed to make the company more competitive.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil information sheet, 23 October 1996. An information leaflet entitled Three steps forward towards 2000 stated: “We will work more efficiently, be open to new modes of working and reduce administrative expenses”.

First adopted at the Kalundborg refinery in June 1998, the BRA project was implemented by all the other entities in turn – with Statfjord as the last in 2001. Amusingly, it might be mentioned that the BRA project was greeted with great interest at the London office. According to Ole Johan Lydersen, the whole staff studied its scope carefully in the search of content which could justify this intriguing but rather surprising choice of project name.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Related by Ole Johan Lydersen on Equinor’s 50th anniversary Facebook page, 5 January 2020.

The big benefit was that many processes could be handled by this one integrated system, rather than utilising a large number of separate software solutions in the various parts of the group. Requisitioning could largely be carried out by those who saw a need, and directly with suppliers who had frame agreements with Statoil.

Another advantage was that people changing jobs within the company ceased to be confronted with new computer tools in a different department. In the longer term, the project management expected annual savings of NOK 1.4 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Teknisk Ukeblad, 19 April 2001.

But critical voices could also be heard. SAP was a rigid system which work had to be adapted to – rather than vice versa. Its functionality was limited and it could only be tailored to a limited extent. When the system was introduced, communication from management was experienced as one-way and massive. There were fine words which did not accord with day-to-day activities. A number of people complained that they failed to master the tool. In some cases, that caused delays and the savings were lower than expected.

SAP nevertheless met a need, and has not been replaced. It covers many oversight functions in the organisation.

Digital road map

During the 2000s, digitalisation developed at a furious pace and with a strength which few predicted, and has eventually come to be utilised in most areas of working life. It provides entirely new opportunities for communicating with offshore platforms and for managing processes in real time from operational support and drilling operation centres on land. A production platform can even be controlled remotely from land, offering major benefits in terms of personnel safety.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor website, 9 November 2017, “Norges første fjernstyrte plattform fra land”.

Statoil adopted a digital road map in 2017. Running until 2020, this called for the investment of NOK 1-2 billion in new digital technology.

The language used by CEO Eldar Sætre when launching the road map recalled to some extent Norvik’s words from 1998, but this new commitment covered other applications than the SAP system. Technological advances had created new opportunities offshore, in particular, for improving efficiency through digitalising work processes. “Our goal is to be a global digital leader in our core areas, and we’re now stepping up our commitment in order to seize the opportunities offered by the rapid progress being made in digital technology,” Sætre said.

A digital centre of expertise was established to help strengthen operational safety. The management expected that digitalisation, combined with standardisation and a culture of continuous improvement, would reduce costs and create the basis for improved value creation and increased activity.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor website, 22 May 2017, “Digitalisering for økt verdiskaping”. Seven digitalisation programmes were identified.

- Utilise data to reduce safety risks, improve learning from past incidents, strengthen security and reduced the carbon footprint of the business.

- Enhance the efficiency of work processes and reduce manual input along the value chain.

- Improve data availability and tools for analysing sub-surface data to support better decision-making.

- Strengthen the use of well and sub-surface data for planning, real-time analyses and increased automation.

- Intelligent design and concept selection for tomorrow’s fields.

- Utilise data to maximise the value of installations through the best possible production and improved maintenance.

- Secure commercial insights and improve decisions with the aid of better analysis tools and data availability.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The day of Big Data had arrived, and Statoil/Equinor was once again an early adopter through this commitment.

Teams in a time of Covid

Digital technology cannot help with everything, regardless of how good the analysis tools available. Viruses are not only a big challenge for computer systems, but in their real-life form can also be a big threat to humans. The world was hit by Covid-19 in 2020. All Equinor employees were required from an early stage to work at home if possible. Travel was reduced to a minimum.

This was when digital technology showed its strengths for both Equinor employees and others. Instead of flying to a meeting, such sessions were held using Teams or other virtual platforms. After a steep learning curve, work and collaboration could continue as before but in a more socially distanced way – thanks to new technology.