Co-owner of oil pipeline

This was to become an important issue of principle for the new entity. The Phillips group – which held the Ekofisk licence – was caught off guard, while Johnsen’s abilities as a strategist became apparent.

A cautious start

The question of landing petroleum production in Norway had a prehistory extending back to the royal decree of 9 April 1965, which laid the legal basis for the first licence awards on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). This stated that, if the King determined it to be in the national interest, he could decide that petroleum products produced should be landed wholly or partly in Norway.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Section 33, royal decree of 9 April 1965.

Nobody knew at the time how this could be achieved in practice. Offshore exploration had barely begun. It was therefore not until gas and light oil were discovered in the Cod field in 1968 that a commission was established to assess opportunities for piping oil to mainland Norway.

Although Cod proved too small to be commercial, the commission submitted a report which found that the deepwater Norwegian Trench along Norway’s North Sea coast represented an obstacle to landing petroleum in the country.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kvendseth, & Phillips Petroleum Company Norway. (1988). Funn! : historien om Ekofisks første 20 år (p. 224). Phillips.: 22.

According to the 10 oil commandments formulated in 1971, petroleum from the NCS had as a general rule to be landed in Norway. The idea was that landing and processing petroleum would help to create jobs on land. There was broad political agreement with this view.

However, the investigation into landing production from Ekofisk concluded that the oil should be piped to the UK and the gas to Germany – even though Norway was nearer.

This decision reflected uncertainty over the viability of operating pipelines which crossed the 350-metre deep Norwegian Trench. The diving technology of the day was not capable of repairing seabed installations in such depths. As a result, the Phillips group applied for permission to lay the pipelines to foreign destinations.

With no experience in this area, the industry ministry needed to establish what terms the government should set when oil and gas pipelines from the NCS were to terminate abroad. That was why the issue was discussed at the state oil company’s board meeting in Stavanger.

The Phillips group had proposed that it should own the pipelines and pay all its costs. But matters were not so straightforward, because the government needed to participate in order to become familiar with the business and to have opportunities for exercising control.

Both the pipelines which the Phillips group had applied to lay would provide transport capacities well in excess of expected output from the fields to be tied into them initially. That much spare capacity could create a monopoly in relation to smaller discoveries unable to justify their own transport system. So it was important for the authorities to secure national control of the system.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 51 to the Storting. (1972–73)Landing of petroleum from the Ekofisk area: 47.

The industry ministry was therefore concerned about two issues – what tariff policy should it follow when licensing a pipeline, and how much of the pipeline should be owned by the state.

Pipeline construction was expensive. That encouraged the government to take a cautious approach. The board of the state oil company recommended that a 10 per cent interest in oil transport systems would be sufficient to begin with.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://media.digitalarkivet.no/view/22486/15. That figure seemed reasonable, since the state had the right to a 10 per cent royalty from petroleum production on the NCS – to be paid either in cash or petroleum.

At the board meeting, however, Johnsen argued that the proportion should be larger since pipeline transport on the NCS would be highly significant in the future. But he failed to win support for that view and, given his relative inexperience, did not want to press the point.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, Utfordringen: Statoil-år, 1988: 24.

From 10 to 50 per cent

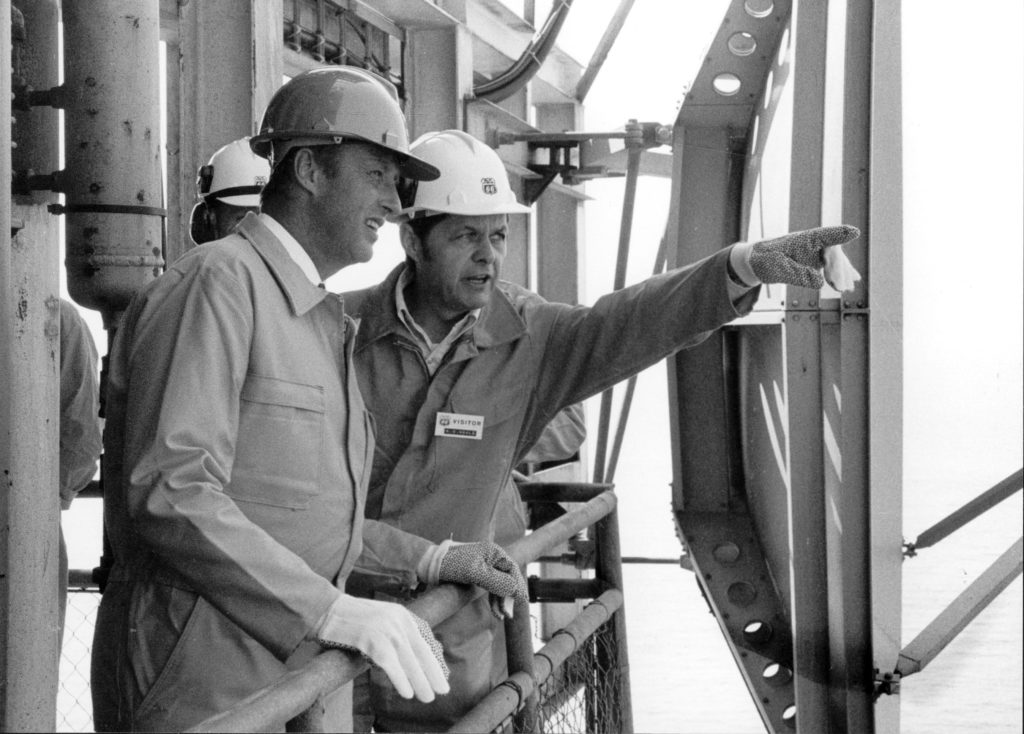

Negotiations began in January 1973 between the Phillips group and a committee appointed by the industry minister, where state oil company chair Jens Christian Hauge and Johnsen were the authoritative voices.

The negotiating team put caution to one side and presented the licensees with new demands. This came as a surprise to Anders Waale, who was on the Phillips group’s negotiating team:

Our view was that the terms in the production licence – paying royalty and so forth, paying tax to Norway, bringing the oil back to Norway and so on, were the conditions determining our right to produce. We weren’t expecting that this Norwegian phenomenon, a new permit for bringing the resources ashore, would involve further conditions. But that’s exactly what happened, of course.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Anders Waale, interviewed by Kristin Øye Gjerde, 2 December 2002.

Secret and intense talks were pursued in several areas simultaneously. A committee led by director general Odd Gøthe at the industry minister negotiated with the Phillips group over ethylene purchases. This petrochemical feedstock was to be sold to Norway at a favourable price and dispatched from the processing plant at the Teesside pipeline landfall in the UK to a Norwegian factory, thereby creating industrial jobs in Norway. These talks went favourably from Gøthe’s perspective.

Another ministerial committee chaired by director general Jens Evensen in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs negotiated with the German and British authorities. This team secured acceptance that companies piping oil and gas from the NCS should be registered in Norway and subject to Norwegian law, and would be wholly or partly owned by the Norwegian state. Transport tariffs for Norwegian products were to be approved by the government, and the same applied to pipeline tie-ins from NCS fields. Norwegian-produced petroleum would have priority over possible other volumes being carried. Norway would be able to tax the pipelines over their full length as well as certain installations on land.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, Nerheim, G., & Norsk petroleumsforening. (1992). Fra vantro til overmot? (Vol. 1, p. 523). Leseselskapet: 295. These provisions gave Hauge and Johnsen good cards in their own negotiations with the Phillips group on the state’s ownership rights to the pipelines.

The industry ministry’s leadership now proposed that the state oil company should have an option to acquire a 25 per cent interest in the pipeline company, to be exercised within two years. Acquiring such a stake would call for NOK 1.5-2 billion in financing, which neither Johnsen nor Hauge was satisfied with. They felt an option solution was too vague, and wanted to secure an immediate holding as well as increasing this to 50 per cent. As Johnsen knew from the history of the oil and gas industry in the USA, companies which owned transport systems were always strongly placed. He felt Den norske stats oljeselskap must also secure such a position.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, Utfordringen: Statoil-år, 1988: 50.

Since the pipeline systems were important throughout the value chain, Johnsen argued, his company should be their half-owner. These entities could have lasting significance for new discoveries, for setting transport tariffs, for prioritising fields in terms of transport, for future earnings by licensees, and for learning about planning, construction and operation of pipeline companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 34.

Where financing was concerned, Hauge and Johnsen recommended a new solution. Participants in the pipeline company would inject 10 per cent as equity, while the users – in other words, the Phillips group – provided the remaining 90 per cent as external capital. “Even the industry ministry’s officials appeared to be taken aback when we presented this proposal,” Johnsen writes in his autobiography.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 32-33.

Phillips incredulous

The heavyweight negotiating team from the Phillips group was no less incredulous when the proposal of 50 per cent state ownership was presented at a meeting on 29 January 1973. It felt powerless and to some extent steamrollered in the talks. On 5 February, the licensees told the government that they rejected 50 per cent state participation, the proposed financing model and the company model. But they were nevertheless willing to accept 30 per cent state ownership.

Johnsen was pleased that the companies had accepted the principle of state participation. Now it was just a matter of pushing ahead. The Norwegians knew that Phillips Petroleum was keen to get started with the pipeline, and that this gave them a negotiating edge. In its response to the Phillips group on 9 February, the ministry listed nine demands. These included the establishment of one or more Norwegian limited companies to own and operate the pipelines. The group also had to accept 50 per cent state participation if the government was to recommend landing the oil in Teesside and the gas at Emden in Germany. Finally, the government wanted the right to supervise and inspect, secure full ownership on the pipelines when the licence period expired and approve possible removal of the installations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 40.

Waale recalls: “We wanted a landfall in the UK, and were willing to accept certain conditions. But each time we felt we’d accommodated the Norwegian government and that message had gone back to the ministry, even more requirements were introduced.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Anders Waale, interviewed by Kristin Øye Gjerde, 2 December 2002. https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/home/.

The Phillips group had little choice. On 14 February, it responded by accepting all the terms in the ministry’s letter but specifying that some would need to be clarified in more detail. “It was pretty brutal,” says Waale. “The Phillips group was to be responsible for 90 per cent of the loan capital and 50 per cent of the equity. That made it responsible for 95 per cent of all costs related to the pipeline while only owning half the company.” But this issue was nevertheless not the one where the biggest battle was fought.

Clash over casting vote

The remaining talks in the second half of February 1973 concerned how much of a voice the state oil company should have. Getting going with the pipeline project was a matter of urgency for Phillips Petroleum, which had already invested substantial sums in good faith to get off to a quick start. But the company thought it was unreasonable that the newly created state company should exercise so much power and authority over the development.

“Statoil had no organisation worth mentioning at the time, nor did it have any experience,” observes Waale. “That it might occupy the driving seat and control our money was just something we couldn’t accept. The banks which were going to lend us money wouldn’t accept it either. That was obviously a very important point.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The negotiations ran into a wall at the end of February over the issue of the role and casting vote of the company’s chair. One of the demands in the letter to Phillips Petroleum dated 9 February was that “the chair shall be selected from Den norske stats oljeselskap a.s”. That was open to two interpretations. One was that the chair would have a casting vote in the event of a tie, which was the normal practice pursuant to Norway’s Limited Companies Act. The other was that the parties would have the opportunity to draw up articles of association which removed the chair’s casting vote.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, Utfordringen: Statoil-år, 1988: 43.

The minutes of the board meeting in Den norske stats oljeselskap held on the same day, 9 February, recorded: “It was agreed that the company would not understand this to mean that the chair was to have a casting vote”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://media.digitalarkivet.no/view/22486/18. That was also Phillips Petroleum’s understanding on this point during the negotiations. “If we’d accepted a casting vote for the chair, our views wouldn’t have counted at all and we’d simply have been left with the full exposure in terms of responsibility for the pipeline,” says Waale.

However, industry minister Ola Skjåk Bræk took the view that the Act should apply, and gave Hauge the job of conveying this to the Phillips group negotiating team on 28 February. That was two days before the White Paper was to be presented to the Council of State (Cabinet).

This was unacceptable to the licensees under any circumstances. The upshot was that Bræk received a visit on the morning before he was due in the Council of State from Fox Thomas at Phillips Petroleum. Looking fairly irritated, Thomas waved an envelope and said “Here’s the mailman” as he presented a letter which had been unanimously approved by everyone in the Phillips group.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Anders Waale, interviewed by Kristin Øye Gjerde, 2 December 2002. https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/home/.

This stated: “We neither can nor will accept that the chair selected by Den norske stats oljeselskap is to have a casting vote.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter of 2 March 1973 from the Phillips group to the Ministry of Industry. Appendix 11. As a result, the White Paper was postponed for consideration by an extraordinary Council of State on 6 March 1973.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.nb.no/items/ca5d169b337b8fa046e221c2401c4473?page=449&searchText=ilandf%C3%B8ring.

Thereafter, the ministry replied to the licensees that the state oil company would continue negotiating with them on an agreement which secured fully satisfactory national management and control of the pipeline company. Providing such a settlement was achieved, the government was prepared to forego the demand for the chair to have a casting vote.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter of 6 March 1973, appendix 12, from the Ministry of Industry to the Phillips group. Negotiations on a shareholder agreement could thereby continue.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes from the board meeting of Den norske stats oljeselskap on 29 March 1973.

The final Storting consideration of the issue took place on 26 April. Waale was in the public gallery and listened to the political debate and the voting, which ended with acceptance of the White Paper on the landing issue by 90 votes to three. He returned to the Bristol Hotel and reported this result to all the top executives in the Phillips group, who had participated in the talks to the end. The news was met with great relief, and everyone was suddenly in a hurry to pass the message on to their respective companies. Pipelaying started just 24 hours after the Storting vote.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Anders Waale, interviewed by Kristin Øye Gjerde, 2 December 2002. https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/home/. That was not normal practice in Norway, but nevertheless typical of the oil industry in many parts of the world.

Not just business

The pipeline company’s purpose was to build, own and operate the transport system which would initially serve seven North Sea petroleum fields: Ekofisk, West Ekofisk, Cod, Eldfisk, Tor, Albuskjell and Edda. It was to be operated on sound, social and commercial principles, and show a reasonable profit.

Full consensus had been reached by mid-May 1973 on a shareholder agreement between the Phillips group and Den norske stats oljeselskap. The company’s board would comprise 12 directors, six from the Norwegian side and six from the licensees – giving each company in the Phillips group one director. Its chair was always to be Norwegian and did not have a casting vote. Statoil’s directors in Norpipe A/S were to be Johnsen (chair), Olav K Christiansen, Tor Espedal, Rolf Quenild, Jon Rud and Erik Schanche.

Each partner was to carry equal weight, and all decisions by the board and general meeting had to be unanimous. In the event of disagreement between Statoil and the Phillips group about the legal interpretation of the agreement, the issue could be submitted for arbitration to a tribunal comprising three Norwegian supreme court judges. The parties were agreed that it was undesirable to end up in such a position, which could affect the company’s operations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, 27 April 1973, “Oljen gir ny energisituasjon”.

Laying the pipelines to Teesside and Emden would cost NOK 5-6 billion. The Phillips group, which was responsible for 90 per cent of this amount, obtained a 10-year loan from America’s First National City Bank. Statoil was to invest NOK 350-300 million in share capital – primarily raised from Norwegian banks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 30 April 1973, “Norsk rørledningskontroll er sikret”. https://www.nb.no/items/f7df89d6dc3f3c574c36ef1ceea67c7b?page=7&searchText=.

A CEO for Norpipe was to be appointed in the near future and would probably have to be a foreigner. But the importance of recruiting the largest possible Norwegian staff for the company was emphasised, with a view to developing personnel and know-how in this area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Minutes from the board meeting of Det norske stats oljeselskap on 16 May 1973.

Johnsen was pleased about the agreements reached with the Phillips group. Together with the rest of licensing terms, these gave satisfactory management and control. A further reason for becoming a co-owner in Norpipe was the opportunities this provided to transport oil from discoveries other than Ekofisk. Statoil would ensure that third parties could obtain socially and commercially acceptable terms. “It’s important to appreciate that we’re not only involved in this for business reasons,” commented Johnsen.

arrow_backStatfjord awardedClarifying Statoil’s governancearrow_forward