West Vanguard blowout

The Smedvig-owned drilling rig had recently been in the Tromsø Patch area of Norway’s Barents Sea sector to drill a successful appraisal well on the Snøhvit discovery. It was now drilling the second wildcat (first well on a prospect) in production licence 092 on the Halten Bank in the Norwegian Sea for operator Statoil.

West Vanguard had reached this location on the evening of 3 October. Although its mooring spread had to be adjusted because of a crashed plane on the seabed, it was ready by lunchtime the next day and well 6407/6-2 could be spudded (started) at 13.30.

The well was intended to investigate Jurassic rocks more than 145 million years old at a depth of 4 000 metres beneath the sea. Gas and condensate were eventually discovered, with the find named Mikkel. However, that was preceded by a serious accident.

Shallow gas

One of the big hazards in drilling is encountering “shallow” gas, held in sandstone “lenses” or thin strata, before reaching the anticipated reservoir. Such deposits are relatively common on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), particularly on the Halten Bank and around Gullfaks in the North Sea.

A site survey conducted before starting to drill a well is meant to identify shallow gas, but will never be able to confirm or deny its presence with certainty.

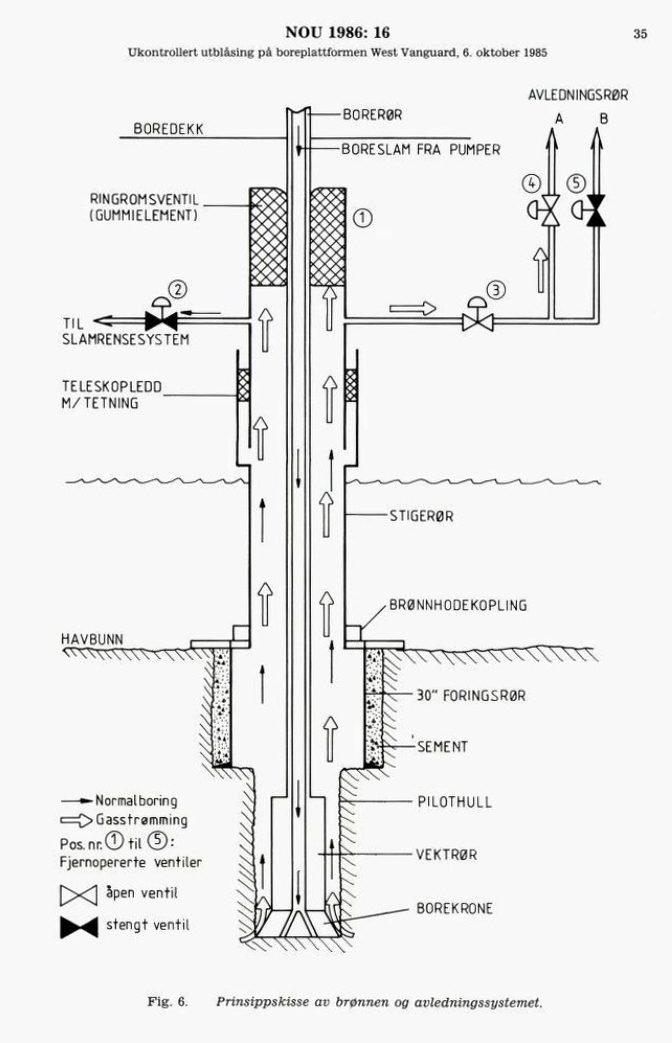

The top section of a well is usually drilled without a blowout preventer (BOP). Any gas encountered should be guided away to leeward of the rig by a diverter system on the wellhead.

Gas alert

Drilling on West Vanguard progressed normally until 20.58, when the bit rather unexpectedly encountered a gas-bearing sandstone formation 506 metres beneath the rig. The site survey had admittedly indicated a possible gas-bearing sandstone layer about 60 metres deeper, and experience of the area also warned that such shallow deposits might be present.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norwegian Official Reports (NOU) 1986: 16. Ukontrollert utblåsing på boreplattformen West Vanguard, 6 October 1985: 8.

Work was suspended temporarily and mud circulated from the hole for 35-40 minutes to remove the gas to the air. Although gas measurements rose, the position was considered stable by both Statoil’s senior drilling supervisor and Smedvig’s senior toolpusher.

Drilling resumed, and gas measurements quickly rose to a new peak at 22.18. Work halted again, and a warning of hazardous gas was issued. Among other measures, welding was banned. Mud circulation continued for 30 minutes and the gas measurements declined. The well was again judged to be stable by Statoil’s assistant drilling supervisor.

Blowout begins

Drilling continued from 22.41 to 22.52, when a new length of pipe was to be added to the drill string. During this operation, such a powerful return flow of mud and gas occurred that it became impossible to remain in the rig’s shale shaker room.

The gas diverter system was activated, and heavy mud began being pumped down the well in a bid to prevent the gas from forcing its way out. This appeared to work for a few seconds, and the noise was reduced even though the gas alarm undoubtedly added to it. But the blowout increased in intensity to a point where it was impossible for personnel to communicate.

The diverter system, which had been tested only days earlier, proved unable to withstand the mix of gas and sand. This abrasive blend wore through the pipes and flowed onto the platform. With the drilling leadership now on the bridge, a full alarm was sounded around 23.15 which required everyone to take to the lifeboats.

The order to disconnect the wellhead connection to seal the well was communicated by one of the drilling crew running over to the cellar deck, where that job was to be done. Just before 23.20, the first explosion occurred. A mushroom of flame was observed around the derrick. Fires broke out immediately and subsequent explosions were registered.

Drill-floor roughneck Alf Oddvar Bjordal was never found. He probably left the subsea control room just before the explosion.

Immediately after the first blast, the offshore installation manager (OIM) activated the release mechanism for the stern anchors. This meant tension on the forward anchors could pull the rig off the well and away from the blowout.

Actually lowering the lifeboats and getting away from the rig was conducted without major problems, and personnel in both boats were taken aboard the Black Ice standby ship within 90 minutes. Evacuation was particularly dramatic for the OIM and stability manager, who climbed down the support columns and swam away in their survival suits before being eventually rescue by Black Ice.

The sea continued to boil with gas, which was still partly aflame, but the rig had moved away from the centre of the blowout. Although the amount of gas escaping declined considerably within a week, a substantial quantity was still flowing from the wellhead six months later and could be seen at the sea surface.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) to operator companies on the NCS, 16 April 1986, Erfaringer fra West Vanguard-utblåsningen – pålegg om tiltak. Appendix to NPD report on the West Vanguard accident: uncontrolled gas blowout well 6407/6-2.

Material damage was massive and amounted to several hundred million kroner. But this could be repaired, and the rig was operational again by the following June, when it made an oil discovery in the same area.

What went wrong?

A commission of inquiry was appointed two days after the accident, and delivered its report on 14 March 1986. This listed a number of “unfortunate circumstances” underlying the incident. Inaccurate reporting, declining confidence in metering equipment, some deficiencies in the well programme and an exaggerated anxiety about increasing mud weight were cited as contributory factors.

In addition came inadequate understanding of how shallow gas blowouts develop, as well as certain deviations from the internal drilling procedures established by the companies.

As early as a month after the accident, the commission’s preliminary findings indicated that equipment had also failed. The rig’s gas diverter equipment, which was a regulatory requirement and functional, proved unable to cope with the stress. Gas under pressure mixed with sand caused “erosive wear” and quite simply wore holes in several of the pipes intended to convey the gas away from the mud room and the rig.

The pressure loss from reservoir to rig was minimal, and the gas poured from pipes at the speed of sound and with “an eerie deafening roar”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Tim Dodson, interviewed by Arnt Even Bøe, Stavanger Aftenblad, 23 February 2001.

On the basis of its findings, the commission recommended that the following measures should be considered:

- better training in and thereby understanding of the shallow gas problem among drilling personnel

- better coordination of well planning

- better metering equipment and further development of systems for handling shallow-gas outflows

- changes to the regulations for using gas diverter equipment in top-hole drilling

- changes to emergency response procedures so that evacuation is ordinarily initiated as soon as a gas diverter system of the traditional type has been activated

- improving fire-prevention measures on a rig, such as placing the air intake to the engine room where the chances of drawing in gas are smaller

- improving escape routes

- assembling all disconnection panels in one safe place

- continuing to develop solutions for moving a rig rapidly.

“The oil industry learnt a lot from the West Vanguard blowout,” Tim Dodson, then exploration vice president at Statoil, commented 25 years after the event.

“Among other results, drilling methods were changed so that shallow gas couldn’t reach the drill floor any longer. New free-fall lifeboats were also developed which hit the sea at a distance from the rig.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The public prosecutor for Rogaland county (which encompasses Stavanger) fined Statoil NOK 1 million for breaching the Petroleum Act. This was because planning and preparation of the drilling programme and the start of the work allegedly failed to take prudent account of the threat posed by shallow gas.

The penalty was discussed by the Statoil board, which took the view that the operation had been conducted prudently but decided that it was not worth disputing the fine in court.