Sustainability and wind power

We need to go back to the 1980s and 1990s to find one of the fundamental reasons for this reorientation. Norwegian Labour Party leader Gro Harlem Brundtland served from 1984 to 1987 as chair of the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development. Its report, Our common future, put sustainable development seriously on the international agenda.

The commission found that burning fossil fuels and releasing greenhouse gases (GHGs) would cause global warming if pursued on a sufficiently large scale. Unless something was done to limit these emissions, the world’s population would face major problems.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Brundtland, G H and Dahl, O, 1987. Vår felles framtid, Tiden Norsk Forlag: 257.

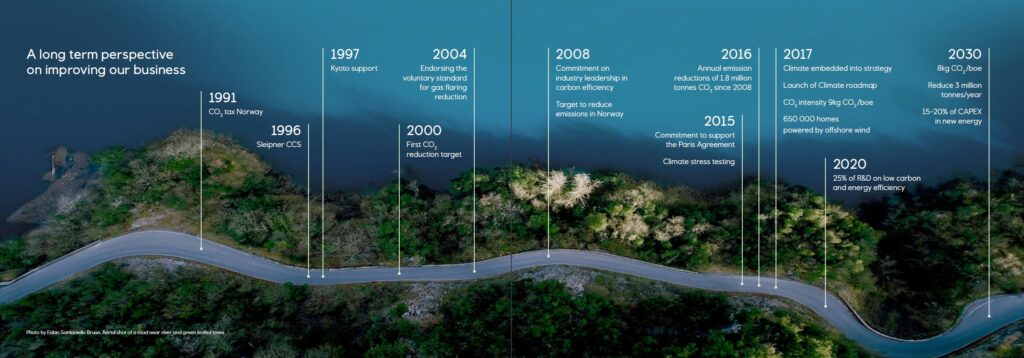

As a result of these recognitions, the Labour government headed by Brundtland introduced one of the world’s first carbon taxes to Norway in 1991.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/stp/19981999/0001/ddd/pdts/stp199819990001skadddpdts.pdf. This set a price on releasing GHGs to the atmosphere, making such emissions more costly for the oil industry and renewable energy less expensive in relative terms.

Through the 1997 Kyoto protocol, Norway and a number of other countries committed to cutting their GHG emissions. Norwegian politicians thereby undertook to identify measures which could help to achieve such reductions. But it proved virtually impossible to get down to the 1991 emission level, as promised. Where Norway was concerned, this particularly reflected the growth of the oil industry and the reality that the biggest GHG emissions came from the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS).

Domestic oil companies Statoil and Norsk Hydro nevertheless wanted to demonstrate to the authorities that they were researching and seeking to try out methods for producing petroleum more sustainably. But their approaches to sustainability and cutting emission were quite different.

Commitment to carbon storage

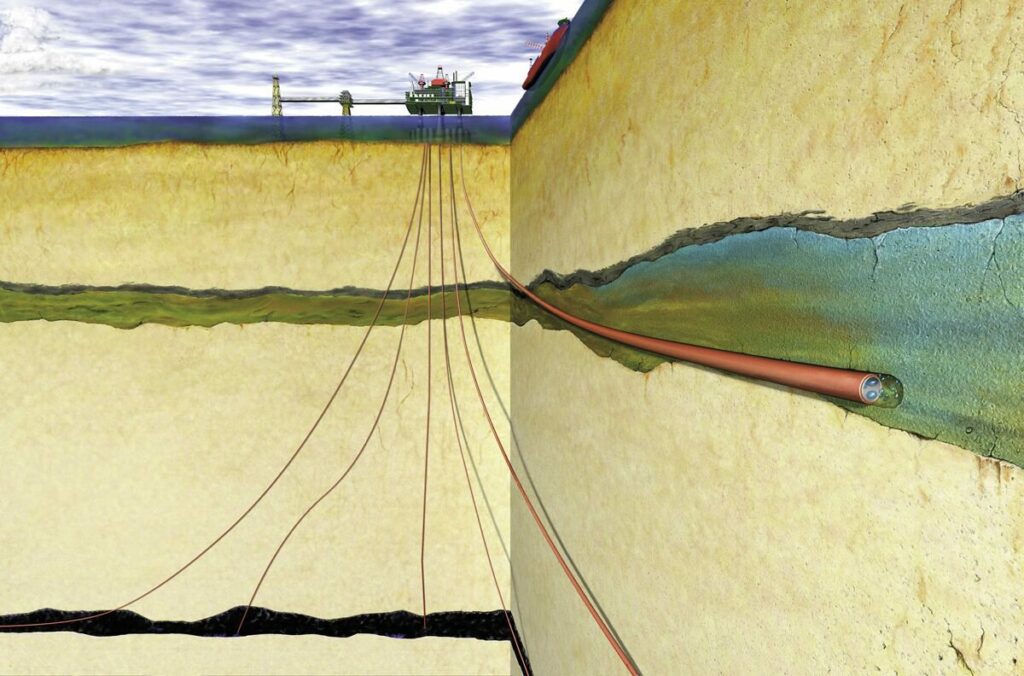

In Statoil’s view, one way to cut emissions was to inject CO2 released from oil and gas production back below ground. Separating out and storing CO2 on Sleipner was primarily intended to make the natural gas from this North Sea field saleable, but it also represented a good climate measure. In any event, Statoil escaped paying tax on the injected CO2. A similar project has been successfully implemented on Snøhvit in the Barents Sea from 2007.

Further research on carbon capture and storage (CCS) at Mongstad near Bergen, known as the “Moon Landing” project, was initiated in 2007. However, this proved so expansive that it was ultimately shelved.

Statoil published its first sustainability report in 2001,[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/h61q9gi9/global/b5f2c765f75d9d95c691cd961f5a7a5707e695e0.pdf?sustainability-report-2001-equinor.pdf. and started work on an initial climate plan in 2007. This was a response to the White Paper published on the subject in the same year. This provided guidelines for the level of ambition which the authorities should set for reducing GHG emissions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 34 (2006–2007) to the Storting, Norsk klimapolitikk, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c215be6cd2314c7b9b64755d629ae5ff/no/pdfs/stm200620070034000dddpdfs.pdf. The government believed the petroleum industry could contribute in two ways – electrification of offshore operations and research on offshore wind power.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 55 and 67.

In the work on Statoil’s own climate plan, the management discussed the need to concretise a continued commitment to renewable energy.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Corporate executive committee meeting, 26 May 2008, item 4: New energy strategy.

The merger with Hydro’s oil and energy division added a new dimension in the form of wind power. This thereby crystallised along with CCS and biofuels as the company’s three most important commitments aimed at reducing GHG emissions.

A specific climate communication strategy was also developed during 2008.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid, item 5: Climate communication strategy.

Hydro and offshore wind power

As noted above, Statoil acquired renewable energy in the form of offshore wind power by merging with part of Hydro in 2007. In pursuing its own approach to sustainability and renewables, the latter had been concerned since the early 2000s to demonstrate that it also wanted to contribute to GHG cuts.

As its name indicated, the company’s background was in exploiting clean hydropower to produce fertiliser and aluminium. It had experience of generating electricity from water – a renewable resource. But Hydro also started investing in wind farms on land in Norway to learn more about this energy form.

Since wind resources are greater at sea than onshore, and Hydro had many oil installations offshore, its creative engineers began thinking about wind power there. The question was whether it would be possible to combine its experience of electricity generation and operating floating oil installations.

The company investigated this possibility in two directions. First, it began developing a concept for floating wind turbines in 2002 under the name Hywind – incorporating the first two letters of Hydro. Second, the EU was running a publicly subsidised programme to encourage the development and commercialisation of large-scale offshore wind power – including in the UK. Hydro wanted to participate in this effort, and acquired a 50 per cent stake in 2005 in a British licence to develop a wind farm at Sheringham Shoal in the North Sea. That marked the beginning of a big commitment to this form of energy in the merged company.

Hywind pilot turbine

At that time, offshore wind farms consisted of turbines mounted on pillars fixed to the seabed. That restricted the water depth for such installations to a maximum of 20 metres. Suitable areas were primarily found off countries with shallow continental shelves, such as the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands.

Since the NCS is largely too deep for fixed turbines, Hydro assessed opportunities for floating units in these waters. Stronger winds were expected to improve their productivity and profitability compared with land-based turbines. Hydro hoped that the potential of this concept for reducing emissions from offshore operations would tempt the government to bear part of the cost for developing the new technology.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Boon, Marten, A National Giant. Statoil and Equinor after 2001, Universitetsforlaget 2022: 334.

When the company began basic work on its wind turbine pilot, the engineers took as their starting point opportunities to combine known technology from petroleum operations – platforms using floating concrete support structures – with knowledge about wind power.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Haugesunds Avis, “Vindmølle i havet utenfor Karmøy”, 10 November 2005. The test floater was to be moored to the seabed by three anchor lines or chains. It comprised three components – a concrete base section, a steel mast carrying the actual turbine, and the unit combining turbine, generator and power cable for connection to the power grid. This unit would be able to stand in waters 200-700 metres deep.

Alexandra Bech Gjørv, who headed Hydro’s new energy department, believed the waters off Karmøy – a large island north of Stavanger – were perfect for testing a floating wind turbine. This location provided deep water close to land. After testing, she maintained that Hydro could envisage moving this Hywind Demo to a place where it might supply an offshore platform with electricity. In that way, CO2 emissions from its oil installations could be reduced.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.tu.no/artikler/hydro-i-vinden/257770. Not many other oil companies were thinking along such lines at the time.

When the merger with Statoil took place, Hywind had still not been realised. At that time, the Centre Party’s Åslaug Haga – who was serving as petroleum and energy minister – said that the government had not done enough with regard to climate change. In line with the climate White Paper, she wanted Norway to become a leader for offshore wind power and said it was important to put the country’s first wind turbine at sea in place.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gimse, S, 2020, Et reklameshow? En studie av Statoils satsing på havvindkraft, 2005-2017, master’s thesis, University of Oslo: 44.

That brought Hywind a step closer to realisation, and it had become part of StatoilHydro’s wind power commitment. When the pilot was installed and brought on line 10 kilometres south-west of Karmøy in the autumn of 2009, it ranked as the world’s first full-scale floating wind turbine.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/energy/floating-wind

Despite much positive attention, Hywind was long an odd-one-out in Norway’s offshore wind power commitment. It was never moved further offshore to supply a platform with electricity. According to Gjørv, making the necessary modifications to an installation for this to happen was probably considered too expensive.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gimse, S, op.cit.

Building expertise off Britain

The other part of the wind power portfolio acquired through the merger was Sheringham Shoal, and this project was the subject of discussions relating to Statoil’s continued commitment in this sector. Experience from the UK facility provided a good basis for a continued offshore wind power involvement.

After Helge Lund took over as Statoil’s CEO in 2004, renewable energy was not given the highest priority. He concentrated on growth in the company’s core business – oil and gas production, particularly abroad. That led to exploration in a number of countries where Statoil had never had a presence before. At the same time, the company shed operations related to processing and sale of petroleum products – primarily the service station chains.

Nor was wind power regarded as a core business after the merger. The wind farms on land in Norway were sold in 2010-11. Gjørv, who had held prime responsibility for this business in Hydro, retained this role in the merged company but felt that renewables received insufficient attention from management.

The wind power unit was renamed renewable energy in 2010 and placed in Eldar Sætre’s marketing, processing and renewable energy business area. He became a source of support for Gjørv. Since Statoil’s management wanted to concentrate the offshore wind power commitment, however, the floating Hywind turbine was all that remained in Norway.

But the commitment in the UK expanded, partly because Statoil landed a big offshore wind licence for the Dogger Bank in Britain’s third round of awards in January 2010. Two years later, it added the Dudgeon licence – next door to Sheringham Shoal – to its portfolio.

Renewables commitment takes shape

Statoil’s ability to secure big areas in British licensing rounds gave the company important advantages – including enhanced expertise with renewable energy. It eventually also permitted the farm-out of licence interests to other oil companies eager to move into renewable energy, which helped to spread the risk.

The company gradually built up experience with an emerging industry closely related to its petroleum operations, with opportunities to develop more legs to stand on.

Progress in the UK showed that, even though the renewables commitment had little visibility under Lund’s leadership, individual projects also took shape in that period.

The breakthrough for renewable energy in the company nevertheless came first after Sætre took over as CEO from Lund in late 2014 and established the new energy solutions business area in 2015.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/h61q9gi9/global/3b3dfed9ee2bf168d83d7551c8257aaf2042d055.pdf?sustainability-report-2015-equinor.pdf.

Sætre took steps to increase the visibility, legitimacy and credibility of Statoil’s commitment to renewable energy. He was willing to accept that, from a climate perspective, the company had to begin a transition in order to be able to deliver clean energy as well – in the same way it had earlier built itself up as a technologically competent oil and gas supplier.

Making a commitment to offshore wind power has increasingly become a question of acquiring competence which can eventually, as the green shift is implemented, provide work for and income to Statoil in a sustainable manner.