Short-lived Asian refinery episode

The Asian economy expanded in 1995 by 7.5 per cent – compared with a growth rate of three per cent for the world as a whole.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, ”Milliard-satsing for Statoil i Asia”, 7 April 1995, National Library of Norway. Since Asia was – and is – the world’s most populous region,[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solerød, Hans and Tønnessen, Marianne, ”Verdens befolkning”, Store norske leksikon, https://snl.no/verdens_befolkning, accessed 16 March 2022. that naturally also attracted attention elsewhere.

Norway’s Labour government under Gro Harlem Brundtland had cast its eye on Asia’s rapidly growing economy, and pursued an “Asia commitment” in 1995-96. That included members of the government, with representatives of the Norwegian business community, travelling to – almost touring – selected countries in the region.

Petroleum, environmental technology, hydropower, ship’s gear and communication systems were identified as particular areas where Norway could acquire a slice of the growing cake.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende, ”Statoil investerer i Malaysia”, 7 April 1995, National Library of Norway. Statoil was one of the companies keen to secure a helping.

Melaka refinery

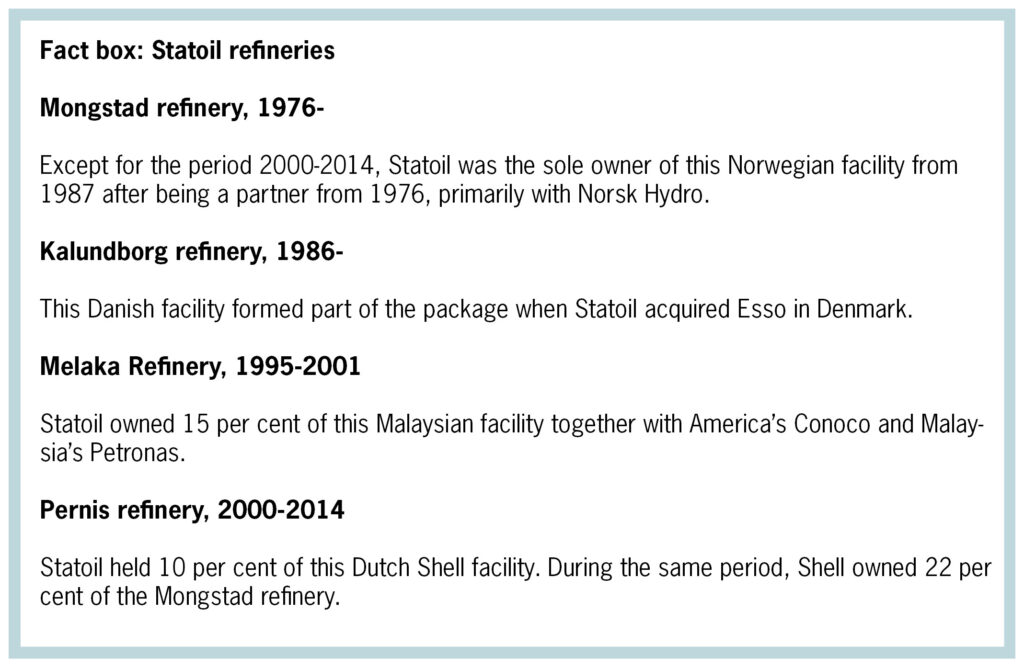

A rapidly growing economy plus a big population equals a region which needs oil and oil products. Statoil characterised Asia in 1995 as the world’s most expansive oil market.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, ”Statoil inn i Asia-raffineri”, 7 February 1995, National Library of Norway. The company was already then negotiating to acquire 15 per cent of the Melaka facility, and this purchase was approved by its board on 31 March 1995.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Board minutes, Statoil, 31 March 1995. Its partners were American company Conoco and Malaysia’s Petronas. An expansion phase under way at the refinery was intended to increase its daily capacity to 100 000 barrels oil when completed in 1998.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Olje fra Nordsjøen gir Statoil gevinst i Asia”, 4 November 1996, National Library of Norway.

Statoil could use its share of the refinery to produce oil products for the Asian market. In the longer term, it also wanted to refine feedstock from its own sources in Asia – such as the Lufeng field off China.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

The company emphasised that this commitment would be commercially profitable and was not being subsidised by other parts of the business. In particular, it pointed out that a shortage of refining capacity in Asia meant owning a facility made better financial sense than leasing one expensively.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid. Statoil was pleased to have the chance to cooperate with its partners in Melaka, whom it regarded as experienced in the refinery business.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, ”Milliard-satsing for Statoil i Asia”, 7 April 1995, National Library of Norway.

Profits from refining had been rising in Asia since the 1980s, and were now higher than in Europe. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1995, Statoil: 27.

But the question is how sensible it actually was for the comany’s reputation to become involved in Melaka.

Compensation claims

Expanding this facility had led to conflicts with the local population. Of the 300 families displaced to make way for heavy industry, 67 were still not satisfied in 1997 with the compensation awarded and had taken legal action. So had 300 fishermen who could no longer work in the waters off the refinery because of new quays and an expanded security zone.

Worst of all, perhaps, the expansion had led to the demolition of two mosques and left two cemeteries inside the refinery site – making it difficult for relatives to visit the graves.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet, ”Opprør mot Statoil-satsing”, 30 January 1997, National Library of Norway.

The criticism was covered in several newspaper articles and also expressed by Norwegian environmental organisation The Future in Our Hands (FIVH). Statoil denied that it had any involvement in the issue because permission for the expansion was given before it acquired its stake. The company’s response was therefore that it would raise the matter with Petronas and Conoco and, after doing so, that it had received satisfactory answers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Leer-Salvesen, Tarjei, 1998, I gode hender? FIVH, Oslo: 30.

Furthermore, the Melaka refinery was criticised for refusing to allow its workers to choose their own union and making them join the Petronas “company” union. That was contrary to the principle of free association, according to the NorWatch monitoring project.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NorWatch was launched by the FIVH in 1995 to monitor Norwegian commercial projects abroad, with a particular concentration on the environment and human rights. It was wound up in October 2010, but the subject is still on the FIVH agenda. Statoil should either come clean and admit that it violated human rights or pull out of countries which did so, Morten Rønning at NorWatch told leading Oslo daily Aftenposten in February 2000. He maintained that this was a particular problem because the company was so concerned with such rights at home.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Anklager Statoil for dobbeltmoral”, 29 February 2000, National Library of Norway.

Despite the criticism, Statoil denied – in response to a direct question – that this was the reason why it sold its 15 per cent share in 2001 to Petronas and Conoco.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Statoil ut av problemraffineri”, 28 February 2001, National Library of Norway. Part of the reason for the sell-out was that the company’s plans in Malaysia and Asia had not developed as intended.

Unfulfilled ambitions

When Statoil bought into the Asian market, it did not regard refining as its only area of commitment and thought of Malaysia as the first step on the road.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kuala Lumpur meeting, 11 August 1997, “Building a retail business in Malaysia”: 1.

Just as Norway and the rest of Scandinavia had been the entry point to the European service station market, the company believed such outlets in Malaysia would be followed by others in Vietnam, China and perhaps other Asian countries. The goal was for its brand to become known throughout Asia.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 1.

Apart from Germany, where profits were too low, Statoil was building ever more service stations in Europe. The specialists who had been based in Germany were relocated to Malaysia, but this country failed to become the entry point to the Asian market.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 3.

The explanation may be that it was difficult for a foreign company to open service stations in a country where the necessary licences were basically only available to Malaysians.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid: 4. Or a decline in the Asian market could have been responsible.

Economic downturn

A research report in 1999 found that the Norwegian government’s Asia commitment had failed to provide the desired results, primarily because of an economic downturn in the region.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Mislykket Asia-satsing”, 22 April 1999, National Library of Norway.

In the mid-1990s, Asian oil demand was expected to be up by a million barrels per day to 1998. The reality in March of that year was a fall of 500 000 daily barrels and oil stores filling up.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil magazine, no 1, vol 21, 1999. Statoil, Stavanger, National Library of Norway: 19.

The underlying downturn was dubbed the Asian crisis, because it derived from a burst property bubble and speculative borrowing in Bangkok.

This decline in demand had knock-on effects for global oil prices. These dropped by almost 50 per cent from the 1997 peak as a consequence of over-production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.

Falling prices also affected the refinery sector. Despite an upturn in April 2000, the short time that Statoil had been a co-owner of the Melaka facility was primarily characterised by decline.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, ”Raffinert bonanza”, 11 April 2000; Bergens Tidende, ”Kan takke oljeprisen”, 22 February 2000, both National Library of Norway. But financial considerations were not the only reason for selling out.

Slimming down

Aftenposten reported in October 2000 that Statoil was already trying to dispose of its part of the Melaka refinery. This was allegedly part of a plan by CEO Olav Fjell to slim down the company ahead of a stock exchange listing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Olav Fjell rydder videre”, 31 October 2000, National Library of Norway.

When the sale had been finalised, preparing for a listing and a desire to streamline the marketing and refining business were indeed cited as reasons.

Although Statoil had many other activities in Asia, such as oil production and crude oil sales, it was made clear that refining in this region would no longer be a core area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, ”Statoil ut av problemraffineri”, 28 February 2001, National Library of Norway.

Statoil would sooner use the resources elsewhere.