Refined swap deal

Conditions for refining were once again poor in Europe around 2000. Profit margins were small, with little difference between crude oil and refined product prices.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Beholder trolig raffineritomten”, 8 September 1999, National Library of Norway. The sector was also suffering from overcapacity, and the EU would soon be imposing stricter environmental curbs on releasing sulphur and aromatics.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, ”Hemmelige møter siden i vår”, 26 November 1998, National Library of Norway. That would demand expensive modifications.

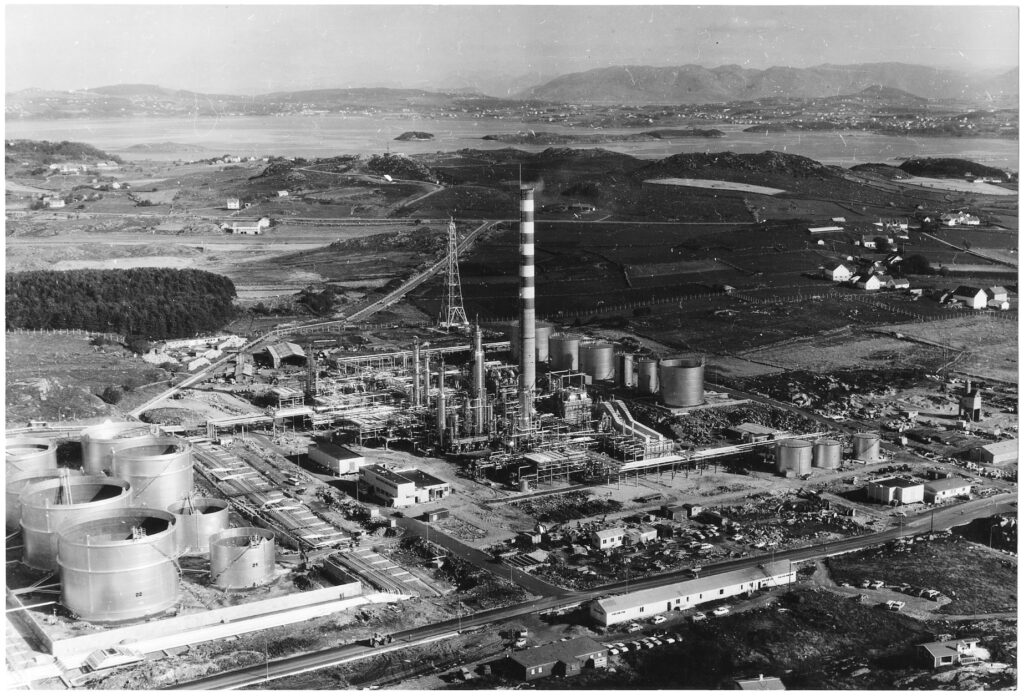

As a result, Shell decided to shut down its refinery at Risavika outside Stavanger from 2000.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagens Næringsliv, “Shell stenger raffineriet”, 27 February 1999, National Library of Norway. This facility was held to be too old and small to justify a conversion. At the same time, the company was interested in continuing to have access to a refinery in Norway, both to process oil from the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) and to meet supply obligations for its service stations around the country.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, ”Beholder trolig raffineritomten”, 8 September 1999, National Library of Norway.

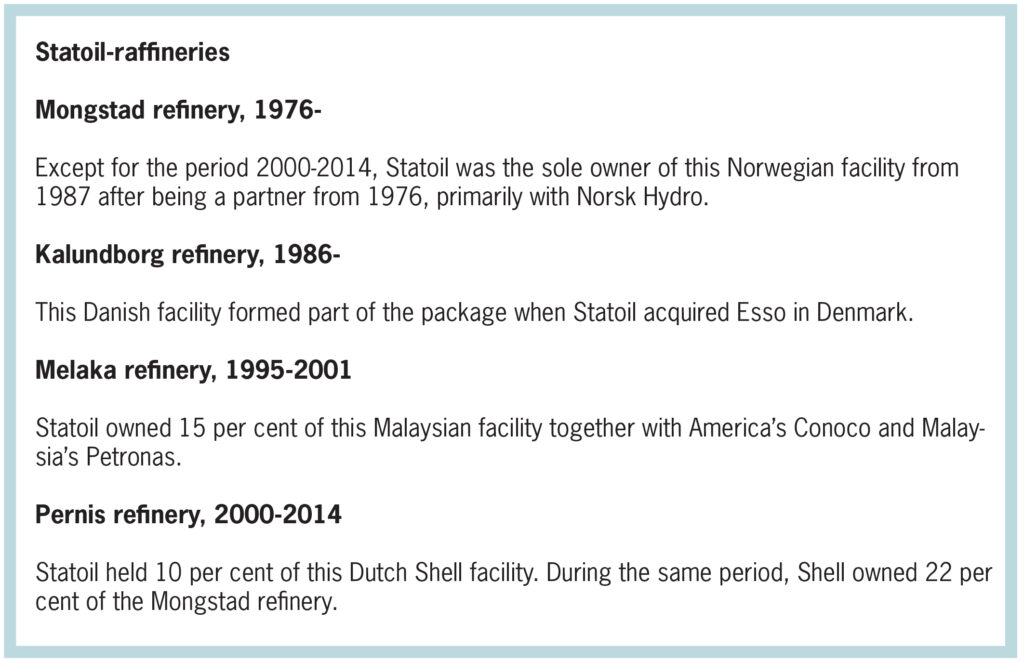

The solution was a swap with Statoil. From 1 January 2000, the latter would own 10 per cent of the Shell’s Pernis plant, while Shell secured a 22 per cent stake in Mongstad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 1998, Statoil: 93. This was a win-win deal, the two companies maintained.

Mutual benefits

Losing a local competitor could be regarded as an advantage for the Mongstad refinery.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogaland Avis, ”Statoil og Shell som parhester”, 14 August 1999, National Library of Norway. In the negotiations over a solution, emphasis was given to earlier collaborations between Statoil and Shell over both the Troll field and the Vestprosess transport and processing system for natural gas liquids.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Strilen, ”Tusenårets byttehandel”, 27 November 1998, National Library of Norway.

Moreover, Statoil wanted somebody to share the cost of expanding Mongstad’s capacity to 10 million annual tonnes and adapting to the EU’s environmental requirements.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, “Hemmelige møter siden i vår”, 26 November 1998, National Library of Norway. Leading Oslo daily Aftenposten also identified an advantage for Statoil of having somebody to share the blame if “future investments or errors there become the subject of political debate here at home”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, ”Shell og Statoil. Rydder og bytter raffinerier”, 26 November 199, National Library of Norway.

To sum up, Statoil and Shell saw mutual financial and strategic benefits from collaborating on the refinery front, both when the agreement was entered into and in subsequent years. Good conditions moreover sometimes prevailed in the sector, as in 2004 when petrol prices shot up because of US shortages.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten, “Bensinprisen på vei mot nye høyder”, 19 March 2004, National Library of Norway. But the collaboration nevertheless lasted only 14 years.

Deal terminated

The swap agreement had allowed Shell to continue refining oil in Norway, while Statoil’s overall capacity did not decrease even though less of its crude was processed in Norway.

At the time, some observers nevertheless pointed out that closing the Risavika facility reduced overall Norwegian refining capacity. Although the Shell plant only handled 2.5 million tonnes of feedstock per annum, that had a value because it strengthened refining capacity in Norway. Three Norwegian refineries, owned by Statoil, Shell and Esso respectively, had only processed about 10 per cent of the oil produced from the NCS. Shutting one of them made that capacity even smaller.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, ”Usikker framtid for Shell-Raffineriet”, 27 January 1999, National Library of Norway.

In the early 2000s, many people still believed it was better to export refined products than crude oil. The aim was to be as integrated an oil company as possible, covering everything from seismic surveying to service station sales.

Statoil explained why it and Shell had agreed to terminate their swap deal from 1 January 2014 as follows: “The agreement … has served the two companies well. However, they both now take the view that it no longer provides added value, and we have agreed to accept the consequences of that.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://e24.no/olje-og-energi/i/5V7l2b/statoil-kjoeper-ut-shell-fra-mongstad; https://www.tu.no/artikler/na-eier-statoil-mongstad-raffineriet-alene/233184, accessed 19 July 2021.

The arrangement had outplayed its role, with the refinery market changing yet again. Statoil was moreover no longer concerned to be an integrated company. Two years earlier, the group had sold the Statoil Fuel & Retail company which had supplied motor fuels to customers in the Nordic region and certain other European countries.

Since 2012, Statoil had only supplied this company – which later changed its name to Circle K – with refined products. It now entered into a similar agreement with Norske Shell.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Strilen, ”Statoil vert heileigar av Mongstad-raffineriet”, 5 December 2013, National Library of Norway.

arrow_backEquinor’s route to the wider worldMexico – brief affair in denationalised watersarrow_forward