Gas on hold in Tanzania

It is not unusual for a number of years to pass between proving an oil or gas field and starting development, with many possible explanations for such delay. This article looks at some of the reasons why it has taken time to get going in Tanzania.

Limited knowledge of offshore production

The country is one of the poorest in Africa and depends on foreign economic assistance and loans. Most of the 56 million inhabitants recorded in 2021 live by farming. Tourism to such destinations as its unique national parks and the island of Zanzibar contributes to foreign earnings. So does mining – particularly for gold.

Norway is among the donor countries which have maintained close contacts with Tanzania over several decades, including its own embassy there since 1975. Statoil’s first contact with the country came in 1982, and it undertook the following year to serve as a consultant for the state-owned Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Tollaksen, Tor Gunnar, 2017, Olje for utvikling – hånd i hånd med norske oljeinteresser?, master’s thesis in history: 95.

Established in 1969 and functioning from 1973, the latter’s objects included making the country self-sufficient in petroleum. Its vision was to become a leading integrated oil and gas company able to compete nationally, regionally and internationally in an environmentally appropriate way.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://tpdc.co.tz/about-us/ Petroleum production could help to improve the country’s economy. But developments have made slow progress. Geological conditions make recovery complicated. Tanzania is also characterised by corruption, much bureaucracy and poorly-developed infrastructure.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.fn.no/Land/tanzania, accessed 28 October 2021.

Deepwater gas

Geological investigations in Tanzania and neighbouring Mozambique suggest big deposits of oil and gas could be present off their shores. But exploration must take place in such deep waters that few oil companies have shown any interest.

However, the technology for deepwater oil and gas production was advancing rapidly. Instead of depending on fixed platforms, it became commonplace from the mid-1990s to use production ships tied back to the wells via subsea installations. That provided much greater flexibility in relation to water depth, as well as opportunities to produce from wider areas. Floater solutions were adopted on a fairly large scale off Norway, Angola/Nigeria and Brazil as well as in the Gulf of Mexico.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, Kristin and Nergaard, Arnfinn, 2019, Getting down to it. 50 years of subsea success in Norway: 297–310.

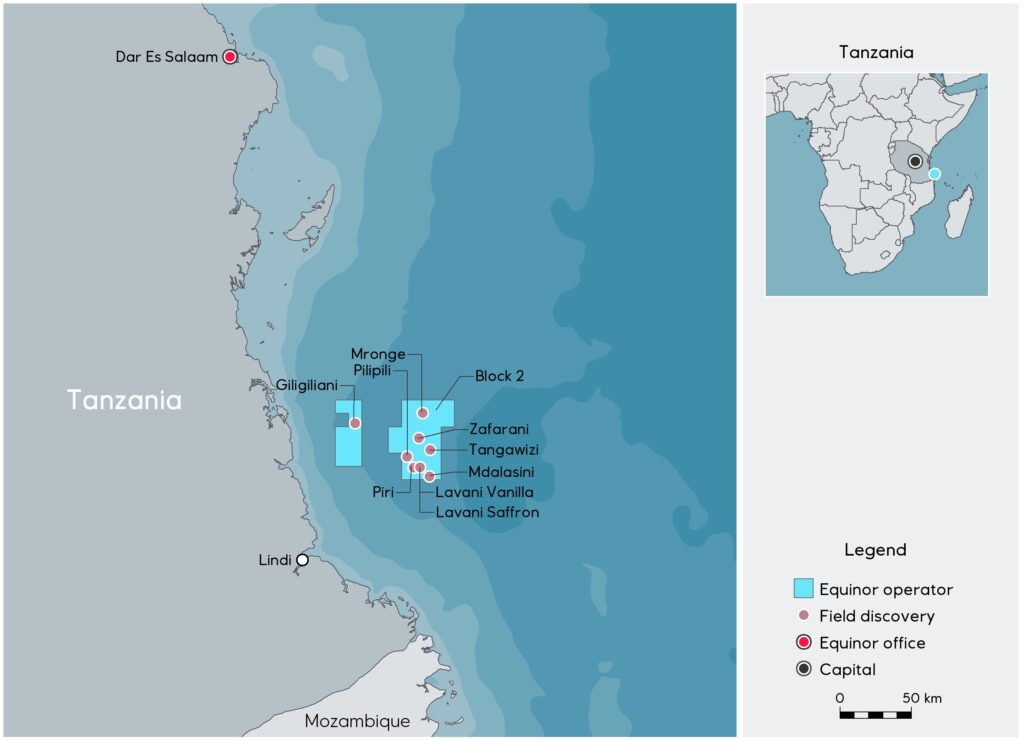

Statoil, which was well in the forefront with developing and adopting subsea technology, decided around 2005 to position itself in Tanzania. It established offices in Dar es Salaam, the country’s biggest city, during 2007 and applied for licences.

In the same year, Statoil Tanzania AS was awarded 65 per cent and the operatorship of block 2. ExxonMobil Exploration and Production Limited held the remaining 35 per cent. The award was conditional on entering into a production sharing agreement with the TPDC which gave it the right to a certain proportion of future revenues from the field.

After acquiring and interpreting seismic data, Statoil was ready to drill its first well in late 2011. The company built up an exploration base in Mtwara, Tanzania’s southernmost town, with a Norwegian manager and many local employees.

A total of six exploration wells were drilled over the next two years in 2 300-2 600 metres of water, which resulted in five huge gas discoveries.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, “Dette blir tidenes største Statoil-utbygging”, 5 April 2013 Statoil then began studying options for developing these.

Shell-owned BG Tanzania also found big gas deposits in two neighbouring blocks during this period. The Tanzanian government asked it and Statoil to collaborate on landing the gas and building a big receiving terminal on land.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2016, Statoil: 33.

Complex development and landing

Erik Holtar, manager for technology and local content at Statoil Tanzania, took the view that the company’s 25-strong staff in Dar es Salaam had to be substantially reinforced in the wake of the major discoveries. Although Statoil could claim experience of landing and processing gas from Snøhvit and from Ormen Lange further south on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS), the discoveries off east Africa were in a class of their own for both size and water depth. Development would thereby require a substantial workforce.

These gas discoveries were in the deepest waters Statoil had so far encountered. Subsea installations, with advanced electronics, sensors, metering equipment and management systems, were to be positioned two and a half kilometres beneath the sea. Involving very high pressures and low temperatures, such depths presented several challenges – including the formation of hydrates (hydrocarbon ice) in pipelines to land, which could cause substantial problems unless the right measures were taken.

Moreover, the very uneven seabed meant it would be challenging to identify the best route for a 100-kilometre gas pipeline to land.

An onshore process plant to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG) also had to be built.[REMOVE]Fotnote: TU, op.cit.

Market for gas

The profitability of a development would depend on LNG prices and how much could be exported. Virtually no market for gas existed in east Africa, so Statoil and its partners would be dependent on selling the LNG to more distant outlets. But Tanzania is favourably positioned geographically for exporting gas to Asia, Europe and South America.

As in Norway, the Tanzanian government required the gas to be landed in its territory. Building a gas liquefaction plant would contribute big investment to the country and create jobs. The licence specifies that local customers can buy up to 10 per cent of the gas. So Statoil’s job was to plan an infrastructure for such sales, and to help establish companies which could use the gas in their business.

Plant plans

Helge Hatlestad was appointed project manager for planning development solutions in Tanzania in 2012, while also chairing the technical committee in the partnerships. One job was to identify a suitable location for the terminal and gas liquefaction plant. Since large quantities of gas were involved, this facility needed to be large – the estimate was four times the size of the Hammerfest LNG plant at Melkøya.

In line with the licence terms mentioned above, 90 per cent of the gas was to be shipped away by LNG carriers while the remainder would be available nationally to contribute to electrification and industrialisation.

The location of the plant was politically sensitive. Extensive protests and riots broke out in Mtwara after it was decided to route the pipeline to Dar es Salaam. These disturbances, which were fairly bloody, were directed against the gas being led away without any economic development in the region.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.aftenbladet.no/utenriks/i/6W3KL/foerst-gasskraft-saa-bondevik.

Partly in order to avoid such problems, the further process for the gas liquefaction plant was very thorough. Both legal and commercial frameworks had to be put in place before the LNG project could be realised. A new draft framework for a national gas policy was presented in 2013.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Towo, Tanisa, “How Tanzania can Avoid the Resource Curse: An Analysis of the Tanzanian Legal and Institutional Framework on the Management of Natural Gas Revenues”, University of Reading law school: 10, cited from Tollaksen, Tor Gunnar, op.cit: 97. Tanzania’s new Petroleum Act, which replaced a 1980 version, came into effect in September 2015.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2015, Oil for Development: 9, cited from Tollaksen, Tor Gunnar, op.cit: 97.

The oil companies had to reach agreement on the commercial terms with the government, which needed to be assured that the project would help to strengthen the national economy. According to Equinor’s website, 60 per cent of the profit after costs are booked will fall to Tanzania.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The offshore tax rate in Norway is 78 per cent of income after depreciation of exploration and development costs.

Constructing the actual plant was estimated to take four-five years, with its commercial life set to last more than 30 years. Where location was concerned, Statoil conducted extensive studies to identify the most suitable sites in terms of technical, environmental and social criteria. Landfall options include areas near the towns of Lindi and Mtwara in southern Tanzania, with the small fishing village of Rhusungi north of Lindi as perhaps the most relevant site. The oil companies submitted their recommendations in 2013. By 2021, the Tanzanian government had still failed to reach a decision on the landfall issue.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hatlestad, Helge, 2021, Femti år med oljeproduksjon. Min historie, (privately published): 291-294.

Still relevant

Statoil/Equinor have invested in Tanzania over many years with a view to preparing the country and the population for a development. Through various programmes, many TPDC employees have studied for a few years in Norway and a lot of them speak Norwegian. Among other measures, Equinor has supported university courses in Dar es Salaam for petroleum engineers, geophysicists and project managers. Backing has also been provided for an entrepreneurship programme and a computer library in Mtwara and Lindi.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://www.equinor.com/where-we-are/tanzania

At present, Equinor cannot offer the graduates of these programmes so many jobs. But that could change if the development of its Tanzanian discoveries becomes a reality.

One reason why implementing the plans has not been a matter of urgency was the 2014-18 oil crisis. After a number of years when petroleum prices were high, global overproduction of oil and gas caused them to decline. That made it less attractive to establish a large new gas liquefaction plant in Tanzania.

Exploration activity has nevertheless continued. A total of 15 wells had been drilled to 2021, yielding nine discoveries with an estimated volume of more than 20 trillion cubic feet in those fields where Equinor is the operator.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Annual report, 2016, Statoil: 33. That is slightly less than total US gas consumption for one year.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Trillion_cubic_feet, accessed 28 October 2021.

If development of block 2 gets under way, the investment required will be in the order of USD 20 billion. That would undoubtedly contribute to growth in the Tanzanian economy, but it is up to the country itself to decide whether it wants this.