Concrete’s dominance – the Gullfaks case

Development solutions rank high among the major decisions in Norway’s oil history. Big financial and strategic interests underlie the concepts ultimately chosen by government and companies.

This article will first present the Condeep design, which often came out on top when development decisions were made. It will then look at some of the reasons for that choice, before turning to Gullfaks and Statoil’s attitude to developing this field.

Condeep

The name Condeep is short for Concrete Deepwater Structure, a Norwegian concept for a platform supported by a gravity base structure (GBS) which sits on the seabed under its own weight. This type of platform was built from around the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s, and is characterised by being very large and heavy. The last Condeep – Troll A in 1995 – stood 472 metres high and had a displacement of 1.1 million tonnes.

A Condeep platform comprises a topsides, primarily in steel, sitting on one or more concrete shafts rising from a set of concrete cells for storing oil. The outer cells extend down to form skirts which ensure a firm grip on the seabed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Larsen, Steffen, 2018, Betongplattformene i Nordsjøen. Utviklingen av Condeep-plattformene og Statoils forhold til plattformkonseptet 1973-1995, master’s thesis in history, department of archaeology, conservation and history, University of Oslo: 36.

The base of a concrete GBS was cast in a dry dock before being towed into a suitably deep fjord for construction to continue upwards. When the steel topsides for the platform were to be installed, the GBS was ballasted down until only a small portion remained above water. The topsides were floated over it, the GBS deballasted, and the complete platform towed out to the field.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For a detailed introduction to building a Condeep, see Sandberg, Finn Harald, 2018, Building the GBS, Industrial Heritage Draugen, https://draugen.industriminne.no/nb/2018/05/14/building-the-gbs/ (accessed 25 April 2022).

Opting for concrete

As a construction material, concrete is very strong and durable. The Condeep concept also allowed the whole platform – GBS and topside – to be made ready inshore. It could then be moved to the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) when weather conditions were suitable. The deep and well-sheltered fjords in western Norway also lie relatively close to the NCS fields, which was a precondition for building this type of structure efficiently. With a platform supported on a steel jacket (framework), much of the outfitting work must be done offshore. That could be a big challenge in waters which are often stormy and rough.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Larsen, Steffen, op.cit: 43. In addition, a concrete GBS could support a larger and heavier topsides than a jacket and provided oil storage which served as a buffer against production shutdowns in bad weather.

Gullfaks

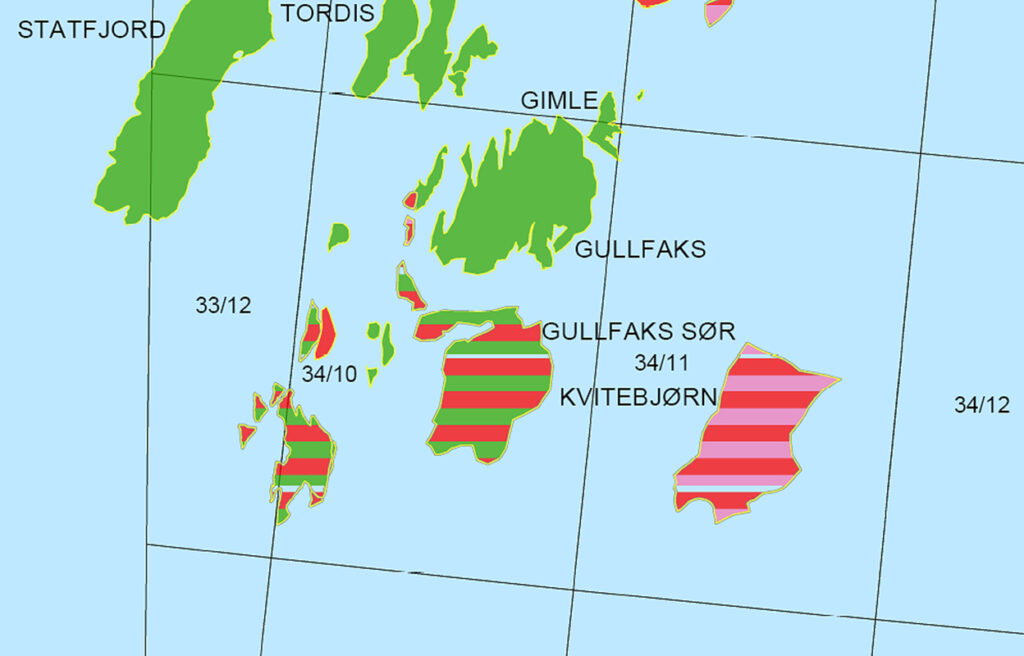

The Gullfaks field lies roughly 200 kilometres north-west of Bergen. Its nearest neighbour to the west is Statfjord, which straddles the dividing line between the Norwegian and UK North Sea sectors. A production licence covering block 34/10 – known as the golden block, which shows the expectations – was awarded in 1978 to the three Norwegian oil companies Statoil, Norsk Hydro and Saga Petroleum. It proved to contain Gullfaks.

This field became a milestone as a purely Norwegian project from the outset, with Statoil, Hydro and Saga holding interests of 85, nine and six per cent respectively. Statoil was the operator – the first time a Norwegian company had been given this responsibility for a large field on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Tønnesen, Harald and Hadland, Gunleiv, 2012, Oil and gas fields in Norway. Industrial heritage plan, 2nd edition, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, Stavanger: 165. But the licensees were not wholly on their own – Esso and Conoco provided technical assistance in the exploration and development phases.

As a symbol of early Norwegian licence-holding and operatorship, Gullfaks deserves a significant place in Statoil’s history. But the field was at least as important for extending earlier development solutions.

Learning from Statfjord

To understand Statoil’s attitude to developing Gullfaks, it is important to know about Statfjord. Developing the latter gave the company its first experience of offshore operations. Operator Mobil took the lead, and Statoil played in many ways the role of an apprentice. The interesting aspect of the field in this context is that it was one of the first on the NCS to opt for a Condeep solution. When this Statfjord A structure had been completed, it was considered desirable – understandably enough – to transfer as much as possible of the experience with this platform to the next. And that continued with Statfjord C, a close copy of the B facility.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Larsen, Steffen, op.cit: 56.

When the time came to develop Gullfaks, Statoil CEO Arve Johnsen decided that Statfjord would serve as the model for the necessary solutions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, Arve, 1990, Statoil-år. Gjennombrudd og vekst 1978-1987. Gyldendal: 127 A number of the engineers who had worked on the earlier field transferred to the new project, and this continuity of expertise strengthened links between the two developments. This meant a tradition was emerging for installing Condeeps on the NCS. Gullfaks ended up, like Statfjord, with three of these structures.

What explanations have been offered for such continuity at an overarching level? One view is taken by historian Francis Sejersted, who has argued that the Condeep was an important part of what he calls “locking-in” a “technology track” – an important technological strategy for Statoil in the 1970s and 1980s. Such locking means that the developers kept to a known concept, making it ever easier to plan while also reducing costs. A complete undergrowth of supplier companies and interest organisations adapted to the concepts, and became an important part of plans for Norway’s petroleum sector to benefit employment on land.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For the full argument, see Sejersted, Francis, 1999, Systemtvang eller politikk. Om utviklingen av det oljeindustrielle kompleks i Norge, Universitetsforlaget, Oslo: 41.

End of an era

Petroleum production in ever deeper waters eventually helped to make platforms supported on a big concrete GBS less relevant. As noted above, the last was Troll A. The sinking of the Sleipner A GBS before mating with the topsides in 1991 also helped to undermine confidence in the concept.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sandberg, Finn Harald, 2018, The Sleipner sinking and Draugen, https://draugen.industriminne.no/en/2018/05/14/the-sleipner-sinking-and-draugen/ (accessed 25 November 2021) That was despite the fact that a replacement was built in record time to avoid delays in meeting gas sales commitments.

Viewed overall, the Condeep was undoubtedly very significant in the history of Norwegian offshore technology. A key element is the way the Gullfaks development established it as a long-lasting solution on the NCS.